High-speed cameras reveal the complex physics at work as air meets water and glass

When a bubble of air rising through water hits a sheet of glass, it doesn't simply stop—it squishes, rebounds, and rises again, before slowly moving to the barrier. This seemingly simple process actually involves some knotty fluid mechanics. An international research team, including researchers at the A*STAR Institute of High Performance Computing, and Nanyang Technological University, Singapore, has now unpicked this physical process.

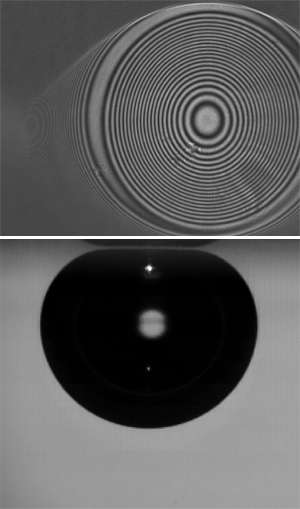

The researchers used a fine capillary to blow air bubbles 0.5 to 1.5 millimeters wide into a glass of de-ionized water. The bubbles rose 5 millimeters before hitting a glass cover, all under the watchful eye of a high-speed camera. Meanwhile, a laser beam shining from above illuminated the contact points between glass, water and the bubble, created a changing interference pattern that was captured by a second camera running at up to 54,000 frames per second (see video).

A bubble typically took about 17 milliseconds to impact, bounce and return to the glass slide. But a film of water remained between them; it took a further 250 milliseconds for that to drain away before the bubble's air came into direct contact with the glass. "The film drains slowly because the process is controlled by viscosity and surface tension," says team member Rogerio Manica. "Eventually, this layer breaks and a three-phase contact line—water, glass and air—forms, with a region on the glass surface that is not wet." This 'dewetting' stage is about 100 times faster than the film drainage process.

The researchers found that a simple mathematical model, called lubrication theory, could accurately describe the film drainage measured in the experiments. "We thus understand the fluid mechanics now in very great detail," says Manica. "Many industrially relevant processes use impacting bubbles, including wastewater cleaning and mineral extraction," he says, adding that simulations of these processes can now be improved by incorporating the team's bubble model.

Other researchers had studied the behavior of much smaller bubbles when rising at very slow speeds. They found that the bubbles settled on to the cover without bouncing, thus skipping the most complex parts of the process.

Manica notes that their experiments also demonstrated the utility of synchronizing cameras to study two very different length scales—the side view is measured in millimeters, while the interferometry camera captures features thousands of times smaller. The researchers are now investigating how rising bubbles behave if the water contains small amounts of other materials, such as surfactants.

More information: Hendrix, M. et al. Spatiotemporal evolution of thin liquid films during impact of water bubbles on glass on a micrometer to nanometer scale. Physical Review Letters 108, 247803 (2012). prl.aps.org/abstract/PRL/v108/i24/e247803

Journal information: Physical Review Letters