May 29, 2012 report

Irish mathematicians explain why Guinness bubbles sink (w/ video)

(Phys.org) -- Why do the bubbles in a glass of stout beer such as Guinness sink while the beer is settling, even though the bubbles are lighter than the surrounding liquid? That’s been a puzzling question until now, as a team of mathematicians from the University of Limerick has shown that the sinking bubbles result from the shape of a pint glass, which narrows downwards and causes a circulation pattern that drives both fluid and bubbles downwards at the wall of the glass. So it’s not just the bubbles themselves that are sinking (in fact, they're still trying to rise), but the entire fluid is sinking and pulling the bubbles down with it.

As mathematicians Eugene Benilov, Cathal Cummins and William Lee explain in their paper at arXiv.org, stout beers such as Guinness foam due to a combination of carbon dioxide and nitrogen bubbles, while other beers foam due only to carbon dioxide bubbles. The nitrogen results in a less bitter taste, a creamy long-lasting head, and smaller bubbles that sink while the beer is settling.

The researchers here are not the first to examine the problem of sinking bubbles in stout beers. During the past decade, experiments have shown that the phenomenon of sinking bubbles is real and not an optical illusion, and simulations have demonstrated the existence of a downward flow near the wall of the glass and an implied upward flow in the middle. But this is the first time that researchers have shown that the mechanism of this circulation pattern depends on the shape of the glass.

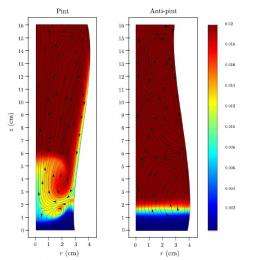

To analyze the effect of different glass shapes, the mathematicians modeled Guinness beer containing randomly distributed bubbles in both a pint glass and an anti-pint glass (i.e., an upside-down pint). An elongated swirling vortex forms in both glasses, but in the anti-pint glass the vortex rotates in the opposite direction, causing an upward flow of fluid and bubbles near the wall of the glass.

The researchers explain that the difference arises from the way the sloping glass walls affect the surrounding bubble density. Once a drink is poured, bubbles start to rise. In the typical pint glass, the bubbles move away from the upward and outward sloping wall as they rise, resulting in a much denser region of fluid next to the wall, with fewer bubbles. Because this region is less buoyant, it sinks under its own gravity. Although the nearby bubbles are still trying to rise, the velocity of the downward flow exceeds the upward velocity of the bubbles, so the bubbles that are close enough to the wall get pulled down by the surrounding liquid.

The opposite effect happens in an anti-pint glass, where bubbles tend to clump more near the oppositely sloped wall as they rise. The increase in bubbles results in a less dense region next to the wall, and fluid near the wall moves upwards.

While this explanation seems to accurately describe observations, the researchers noted that they are still uncertain of the specific mechanism responsible for reducing the bubble density near the wall for the pint geometry and increasing it for the anti-pint one.

The researchers also noted that the same flow pattern occurs with other types of beers, but the larger carbon dioxide bubbles are less subject to the downward drag than the smaller nitrogen bubbles in stout beers.

For armchair physicists, a simple experiment can confirm the proposed explanation. If Guinness is poured into a tall cylindrical glass and the glass is tilted, bubbles move upwards near its upper surface and downwards near its lower surface. In this case, the upper surface acts like an anti-pint glass and the lower surface acts like a pint glass.

The research has a practical side to it as well: designing better beer and champagne glasses, as well as containers for industrial processes involving “bubbly flows.” As for the most direct application, the researchers suggest that the settling time of a stout beer could be significantly reduced by pouring it in some other shape of pint glass.

More information: E. S. Benilov, et al. "Why do bubbles in Guinness sink?" arXiv:1205.5233v1 [physics.flu-dyn]

Abstract

Stout beers show the counter-intuitive phenomena of sinking bubbles while the beer is settling. Previous research suggests that this phenomena is due the small size of the bubbles in these beers and the presence of a circulatory current, directed downwards near the side of the wall and upwards in the interior of the glass. The mechanism by which such a circulation is established and the conditions under which it will occur has not been clarified. In this paper, we demonstrate using simulations and experiment that the flow in a glass of stout depends on the shape of the glass. If it narrows downwards (as the traditional stout glass, the pint, does), the flow is directed downwards near the wall and upwards in the interior and sinking bubbles will be observed. If the container widens downwards, the flow is opposite to that described above and only rising bubbles will be seen.

via: BBC and Technology Review

© 2012 Phys.Org