Universality of charge order in cuprate superconductors

Charge order has been established in another class of cuprate superconductors, highlighting the importance of the phenomenon as a general property of these high-Tc materials.

The discovery of superconductivity in cuprates, a class of ceramic materials, in 1986 has boosted an impressive effort of research all around the world. These materials still hold the record for the temperature where lossless conduction of electricity can be obtained. This is why they are called high-Tc superconductors, despite the fact that high-Tc means only minus 140 degrees centigrade. While this seems rather low, it is in fact very high compared to classical superconductors discovered at the beginning of the 20th century, where cooling close to the absolute temperature zero, minus 274 degrees, is required for the emergence of this exotic, yet very useful property. The exciting jump of the transition temperature with the discovery of the high-Tc superconductors still nurtures hope that lossless conduction of electricity may be possible close to room temperature some day.

Still not well understood: High Tc Superconductivity

The phenomenon of superconductivity is well understood—for the classical superconductors. When not being in the superconducting state, classical superconductors behave like metals, and superconductivity emerges from this metallic state by the pairing of electrons. Pairing of mobile charge carriers is also what is behind the superconductivity of the cuprates. However, these ceramic superconductors are materials, where even the non-superconducting state is hardly understood, let alone the mechanism behind the pairing of the charge carriers. This is why new insights into the properties of the cuprates still keep scientists excited—even almost 30 years after the discovery of high-Tc superconductivity.

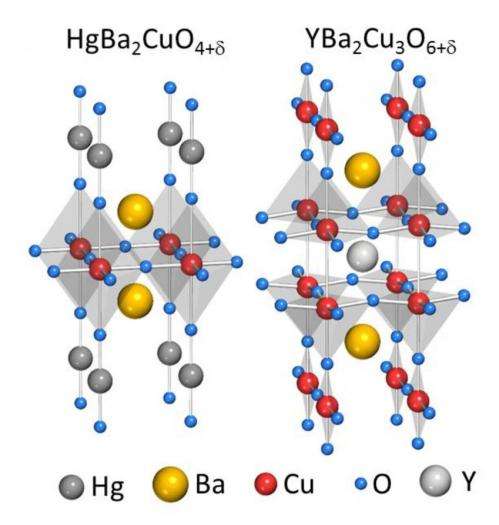

When Copper and Oxygen atoms form planes

The cuprates come as a zoo of materials with abbreviations like LBCO, YBCO, LSCO, BSCO, and many more, with chemical formulae of La2-xBaxCuO4, YBa2Cu3O6+, La2-xSrxCuO4, Bi2Sr2-xLaxCuO6+. All these materials have one common feature: Copper and oxygen atoms are arranged in planes, forming quasi two-dimensional objects. Introducing charge carriers into the copper oxygen planes does not result in a simple metallic behavior. Rather, a complexity of unusual phases around superconductivity is observed, and how the superconducting state develops from these exotic states of matter has escaped explanation up to now.

Charge order in cuprates

One of the phenomena observed in high-Tc cuprates is the so-called charge order. Here, the charge carriers that are introduced into the ceramics to make them conducting in the first place, tend to form a regular pattern of stripes in the copper oxygen planes. Being placed in a regular arrangement renders the charge carrier less mobile and impedes the formation of the superconducting state: Charge order is antagonistic to superconductivity. This is of course of highest importance for exploring the limits of superconductivity and understanding the phenomenon itself. Charge order was observed in one of the cuprate classes already in 1995. It took, however, quite some time to reveal that many other classes of cuprates exhibit the same behavior, and only in recent years evidence for an ubiquitous phenomenon was accumulated, with the important observation of charge order in YBCO in 2012. All these experiments provided evidence that this phenomenon is a common property of charge carriers in copper oxygen planes in the cuprates.

New results show universal pattern and interesting relations between effects

Initiated by researchers from Minnesota, an international team of scientists has now identified charge order in HgBa2CuO4 , emphasizing this universal behavior: HgBa2CuO4 is a pristine cuprate material with a rather simple crystal structure that superconducts at temperatures as high as minus 175 degrees centigrade. A further important result of the study is the finding that the charge order is closely related to another property of the material. When a very high magnetic field is applied, superconductivity is destroyed, and the electrical resistance goes up and down with changing magnetic field, which is known as quantum oscillations. Finding a universal connection between the period of these quantum oscillations and the spatial period of the charge order is one of the achievements of the study. Linking such seemingly distinct observations for a such a complex material is of utmost importance, as it helps to tell which effect is important and which is only spurious.

Discover the latest in science, tech, and space with over 100,000 subscribers who rely on Phys.org for daily insights. Sign up for our free newsletter and get updates on breakthroughs, innovations, and research that matter—daily or weekly.

The tool: XUV-Diffractometer at UE46_PGM1-BEamline of BESSY II

An important part of this research was carried out with the XUV diffractometer at the HZB, employing the particularly sensitive method of resonant soft x-ray diffraction. This method has already been used successfully to detect the weak charge order in a number of materials in the past, in close cooperation with scientists from HZB who operate the instrument at the UE46_PGM1 beamline at BESSY II. The results are now published in Nature Communications. 'After decades of research, the unusual states of matter in the cuprates and their relation to the phenomenon of high-Tc superconductivity are still puzzling the scientists', says Dr. Eugen Weschke from the Department Quantum Phenomena in Novel Materials at HZB, ' the observation of charge order in this clean model system adds an important piece to the systematics of the cuprates, and we are happy having contributed to these studies by a number of experiments here at HZB by now.'

More information:

W. Tabis et al., Charge order and its connection with Fermi-liquid charge transport in a pristine high-Tc cuprate, Nature Communications 5, 5875 (2014).

DOI: 10.1038/ncomms6875

Journal information: Nature Communications

Provided by Helmholtz Association of German Research Centres