Putting more science into the art of making nanocrystals

Preparing semiconductor quantum dots is sometimes more of a black art than a science. That presents an obstacle to further progress in, for example, creating better solar cells or lighting devices, where quantum dots offer unique advantages that would be particularly useful if they could be used as basic building blocks for constructing larger nanoscale architectures.

Andrew Greytak, a chemist in the College of Arts and Sciences at the University of South Carolina, is leading a research team that's making the process of synthesizing quantum dots much more systematic. His group just published a paper in Chemistry of Materials detailing an effective new method for purifying CdSe nanocrystals with well-defined surface properties.

Their process uses gel-permeation chromatography (GPC) to separate quantum dots from small-molecule impurities, and the team went further in characterizing the nanocrystals by a variety of analytical methods. A comparison of their purified quantum dots with those purified by the traditional method of multiple solvation and precipitation cycles underscored the utility of the new method in preparing uniform semiconductor nanocrystals highly amenable to further synthetic manipulation.

Quantum dots

Quantum dots, which are nanocrystals with diameters in the range of 5-10 nanometers, have optical and other physical properties different from those of larger crystals. The reduced size allows them to absorb and emit different colors than bulk quantities of the same compound because of quantum mechanical effects; they also have very large surface-to-volume ratios and can be sensitive to surface treatments.

Greytak's laboratory typically prepares quantum dots in hydrophobic solvents (such as 1-octadecene), so they come out "capped" with hydrophobic molecules and dissolve readily in nonpolar solvents. "The way the process works, you always have a significant amount of unreacted starting material, high-boiling solvents and extra surfactants in there that are important to the synthesis," said Greytak. "But once the synthesis is complete, they're impurities that need to be removed."

The historic method of quantum dot purification is cycles of solvation, precipitation (such as with alcohol), decanting of impurities and re-solvation. Although the method has been in use for some 20 years, it has a fundamental shortcoming.

"With the precipitation and redissolution process, it's not actually doing the separation on the basis of the size of the particle, it's doing it on the basis of the solubility," said Greytak. "So if you have impurities that have solubility qualities similar to those of the particle, they aren't removed."

Gel-permeation chromatography

Greytak directed his team, which included graduate students Yi Shen, Megan Gee and Rui Tan, in developing GPC as a highly effective alternative. A size-exclusion technique, GPC separates chemical species according to molecular weight and is commonly used with macromolecules.

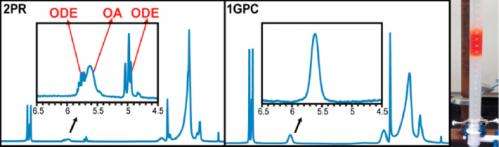

Compared with materials prepared through the precipitation and re-solvation process, the GPC-purified quantum dots had much better stability at high temperature. Moreover, a series of NMR measurements assisted by USC research associate professor Perry Pellechia indicated that the GPC method was much more effective in removing weakly adsorbed ligands from the quantum dot surface.

Carrying a synthetic process forward

The team further examined the suitability of the quantum dots for further synthetic manipulation. Again, the GPC-purified products were superior, both in CdS shell growth on CdSe quantum dots as well as ligand exchange of cysteine on CdSe/CdxZn1-xS quantum dots.

Greytak sees the method as a fundamental step forward in being able to further manipulate quantum dots, whether in constructing larger architectures or asserting control over how the nanocrystal colloids behave in solution.

"What we like to say is that we're developing a sequential, preparative chemistry for semiconductor nanocrystals," said Greytak. "In most synthetic chemistry, you have a starting material, you do a reaction, and you proceed through a series of intermediates with well-defined structures that can be isolated. For a nanomaterial, it's much more difficult, because we're not making molecules, we're making a population of particles that has, let's say, a radius of two nanometers. They aren't all identical, and achieving a consistent product has been challenging, both in terms of how to isolate it and characterize it.

"So we're really working toward being able to characterize a sample, with, say NMR and thermogravimetric analysis, and being able to really predict with confidence how it's going to react in a subsequent step."

Journal information: Chemistry of Materials

Provided by University of South Carolina