Who's your neighbour – and what difference does it make?

Who do you meet in the corner shop or at the bus stop? Whose kitchen window is opposite yours? While diversity is increasing in cities, some groups are becoming ever more isolated.

A new study of geographical changes between 1995 and 2010 shows that segregation is increasing in Stockholm. Researchers have compared demographic and socio-economic conditions. They have also used nearest neighbour data, for example an individual's 5 closest neighbours, or 10, or 100.

The calculations have been carried out by a computer program developed by John Östh, researcher in cultural geography at Uppsala University, and show that segregation is increasing.

'The most notable aspect is the major increase in economic segregation, with poor people being more isolated today than previously and with large numbers of those close to a poor person also being poor themselves. Even more isolated is the rich group, who are living more separate lives than previously and who to an ever greater extent live their everyday lives encountering poor individuals rarely or not at all', say the researchers.

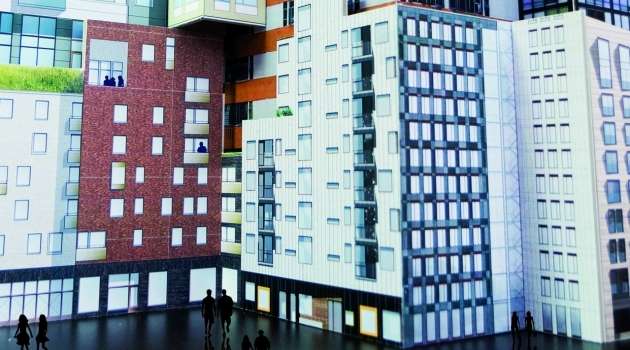

At the same time a new thesis shows that town planning in Stockholm reinforces this trend. 'Town planning is market oriented and its objective is to encourage growth, with social objectives taking a back seat', says cultural geographer Jon Loit.

He has investigated the planning of two entirely different housing areas: the change programme for the tower blocks around the Järvafältet area within the framework of the Järvalyftet programme, and the new town development area of Norra Djurgårdsstaden.

'Overall, Stockholm's town planning can be expected to result in an exclusionary city reserved for inhabitants with work and higher incomes', observes Jon Loit.

He says that planning is leading to segregation becoming entrenched and that Stockholm continues to be a divided city. In particular, the planning and construction of a lifestyle area like Norra Djurgårdsstaden for strong socio-economic groups means that segregation is reinforced, as differences between housing areas persist.

'With its current orientation, planning is not a solution to segregation but instead an additional problem', says Jon Loit.

His research forms part of the 'Dilemmas of diversity' research programme at the Institute for Housing and Urban Research (IBF) in Uppsala. Research manager and cultural geography professor Roger Andersson explains that although the research is focused on Sweden it has aroused major international interest.

'The basic questions are extremely relevant now that both immigration and racism are on the increase. Almost all of Europe is facing a future with a rapidly increasing older population, while the birth rate is falling. One thing that could provide a solution to the problem is immigration from non-European countries. At the same time resistance to immigration is increasing. It's a structural dilemma shared by many countries', says Roger Andersson.

The question of segregation is complex, because different values come into conflict. For example, we all have a basic right to decide where we want to live. At the same time, society has its own views and wants less segregation.

'There is a tendency for many native Swedes to demonstrate avoidance behaviour and leave areas with few Swedes. At the same time they are completely entitled to make these decisions. It's the dilemma between the free choice of the individual and the sometimes undesirable collective outcome of that same choice', says Roger Andersson.

Two phenomena are behind this development. Partly the fact that many new Swedes, not least for financial reasons, are excluded from large parts of the housing market and restricted to a few housing areas dominated by rental units. And partly the fact that many of the people belonging to 'mainstream society' choose to move away from housing areas inhabited by people from different cultures.

The most important factor in the choice of housing is, of course, the individual's financial circumstances.

'In the last 20 years, we have had a situation with much stronger socio-economic segregation and increasing social differences. Previously we had many mixed housing areas, but now the poorest people have become poorer and this stimulates ethnic segregation.'

But does where you live really have such a major impact on your life, education, career and health?

One thing is certain: it plays a major role in a city, where a kind of geographical sorting is in operation—contributing, for example, to the choice of schools or leisure activities.

'Even in a smaller town the neighbourhood plays a role. But on the larger scale, the neighbourhood is responsible for sorting more than simply housing.'

Of course where you live in relation to environmental disruption plays an enormous role.

'We know that poor people live in worse environments, for example close to noisy and dangerous roads or with poor access to different types of service such as schools and elderly care, and this naturally has a major impact on their lives. When it comes to neighbours and your relationships with them it becomes even more complex, as our social networks aren't linked to our housing.'

This applies particularly today, as the free choice of schools has made it possible to choose a school in another part of town. As children grow up, the choice of school is therefore perhaps even more decisive than the location of their home.

'In terms of the adult employment market and careers, it has been shown that it is easier to get back into work if you live in an area where many other people have jobs. We know that networks are important for income development.'

Housing areas change constantly, as do their inhabitants. In Sweden we have good opportunities to monitor this development.

'We have built up a strong research profile in Sweden with register data which means that we can follow individuals and households over time. We have a major advantage in Sweden because we have made major investments in data supply', says Roger Andersson.

And the latest research shows that segregation is increasing in Stockholm, which affects what happens in everyday life.

'We have a welfare policy which is based on the rights of the individual. If it turns out that sorting of life opportunities is occurring on the basis of where someone lives then we need to employ additional resources.'

There is today a growing group of people who can't afford to remain in their homes as a result of rent increases, for example in the Million Programme flats in Stockholm suburbs. These are large housing areas which were constructed in the 1970s and which came to be inhabited by the most vulnerable in society.

These are now being refitted and renovated, with the result that rents are increased and many people are being forced to move because they cannot afford to remain; 25% of residents according to a 2014 report from the Swedish National Board of Housing, Building and Planning. Sara Westin is one of the researchers who has investigated the problem of 'renoviction', which resulted in reports including '...but where can we go next?' ('…men vart ska vi då ta vägen?'), which was commissioned by the Swedish Union of Tenants.

'The overall conclusion is that it is necessary to continue to challenge beliefs about how renovation should function', says Sara Westin.

For property owners, renovation can be an opportunity to raise standards and attract new tenants. In their eagerness to maximise their profits, they can undertake an overly luxurious renovation and raise the standard to a level that the residents can't afford.

'We are in a period in which so-called business principles control the Swedish housing market. The property owners themselves emphasise the importance of 'market adaptation' and the desire to 'reach new customer groups'. If you want to reach new customer groups, that means that other people have to move out.'

There are opportunities to make an impact, for example through the Swedish Union of Tenants, but it is difficult as an individual tenant to refuse a renovation even if it will mean a rent increase.

'Our study shows that the process which precedes a renovation is often not democratic. The tenants have very little opportunity to affect the level of renovation.'

Professor Irene Molina has long monitored the Million Programme in her research and she feels that the situation is serious.

'We are in a housing crisis, not on the housing market but for people who have nowhere to live or who see their housing threatened. We need to mobilise all of our forces to do something about these problems.'

One opportunity for this was the latest Housing Meeting organised in the autumn by the Institute for Housing and Urban Research. The participants included several actors in the housing market—politicians, officials, municipal employees, the County Council, the Swedish National Board of Housing, Building and Planning, SABO and the Swedish Union of Tenants.

'We consider that our mission is important—housing issues affect us all on a daily basis. So we collaborate constantly with other actors', says Irene Molina.

Provided by Uppsala University