Europe's courts under reform pressure: study

Protracted legal proceedings, increasingly complex legal cases and growing criticism of the administration of justice – the European Court of Justice in Luxembourg is overburdened. Research by the Hamburg-based Max Planck Institute for Comparative and International Private Law examines the issues facing the European Court of Justice for the first time and has proposed well-founded solutions that enrich a largely unknown reform debate.

Whether it is buying a car, going on holiday or taking out an instalment loan, few aspects of our everyday lives are conceivable today without reference to European Union law. Countless directives and regulations, which set out the rights of consumers and entrepreneurs, apply not only in international legal undertakings, but also in domestic legal transactions. Which party has the law on its side is increasingly dependent on the European Court of Justice in Luxembourg, which ensures the implementation of European law within the EU.

However, the Court of Justice is facing major challenges: “The dramatic increase in legal cases, protracted proceedings and a major extension of the scope of its responsibilities are stretching the EU’s Court of Justice to the limit,” explains Hannes Rösler, whose research examines for the first time the problems of the European judiciary not just from a legal viewpoint, but from social, political science and economic perspectives as well.

Major challenges for Europe’s judges

The expert on European law at the Max Planck Institute for Comparative and International Private Law in Hamburg has identified the key issues the EU Court of Justice must address now and in future, in particular the shifts of issues to be dealt with, as well as the burden of decision-making and the duration of proceedings at the European courts.

The Court of Justice’s mandate, which has changed radically since 1985 as a result of the single market programme, is of major significance in this respect. Originally conceived as a purely administrative and constitutional court, the Court of Justice must increasingly deal with matters of civil law owing to the preliminary reference procedure. “The judges in Luxembourg constitute a supranational court beyond national jurisdiction, dealing with an incredibly diverse range of issues that no national judge is faced with,” Rösler points out. The reason for this is that, if a legal dispute gives rise to issues that are unresolved under EU law, the judge at the competent court of last resort must refer the case to the EU Court of Justice for a preliminary ruling. He may only pass judgement on the case after its ruling. However, in contrast to national judges, the EU judges are not specialized in specific fields. The only exception is the Civil Service Tribunal, which is responsible for cases under civil service law.

No means of curbing the flood of cases

The greatest problem facing the EU judges – the dramatic rise in the number of cases – can also be seen in this light. Since the first referral in 1961, the number of preliminary ruling cases has increased from one to 385 in 2010. At the same time, the number of cases at all three EU courts rose to 1,406 in 2010. “That’s the highest level in the history of the EU Court of Justice. With the exception of the European Court of Human Rights, the EU Court of Justice has the biggest workload of any international court,” Rösler adds. This also has an adverse impact on the professional quality of the rulings. A certain susceptibility to error exists, in particular on account of the vast detail in private law.

The length of proceedings, which average 17 months, also presents problems. “Combined with the duration of proceedings at the national courts, a case in Germany consequently often takes over four years,” Rösler estimates. Critics believe this is too long. In individual competition law cases, the lower EU court has skirted close to the limits of constitutional legality. In 1998, a company took action over excessively protracted proceedings at the EU General Court and won its case on appeal before the European Court of Justice (Baustahlgewebe GmbH / Commission, C-185/95 P).

More law, greater workload

Various reasons explain the heavy workload. Rösler believes that the EU’s geographical expansion in the past is just one reason why the EU judges face an excessive workload. However, the number of judges has increased by one with each Member State at both the EU General Court and the European Court of Justice. Rösler regards as the main reasons the increasing number of norms under EU law, which constantly give rise to questions of interpretation, and the continual extension of the court’s decision-making powers without support in terms of expertise and personnel. The court’s jurisdiction also increases its workload. “With the growing number of partially also unclear rulings, the EU judges are constantly raising new questions of interpretation and in turn creating new questions referred for preliminary ruling,” says Rösler, summing up the growing concern in academia.

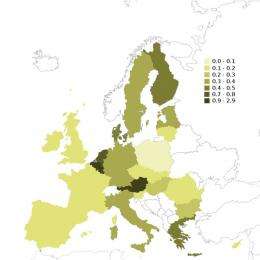

Rösler finds the differing behaviour of the national judges in terms of referrals for ruling of great interest. Some Member States make few such referrals, whereas others make many more. Austria’s judges frequently call upon their colleagues in Luxembourg. One conceivable reason is a ruling of the European Court of Justice against the Austrian state, which stipulated that the state was liable under EU law for jurisdictional error.

Reform as opposed to facelift

Rösler says that reform is the only way out of the predicament, a call backed by the EU judges. Last summer, Vassilios Skouris, the President of the Court, highlighted the Court of Justice’s excessive workload in a public statement. Among other things, he called for 12 new judges to be appointed at the European General Court. The proposal was met with understanding by the Commission in its opinion statement of September 2011.

Hannes Rösler believes that this does not go far enough: “The expansion of the Court is urgently needed, but does not resolve the multi-faceted issues.” A system of judicial federalism needs to be developed between Member State and European courts. Above all, structural reform that establishes a new European judicial architecture should be aimed at. This would also require the Court of Justice to specialize in relevant areas. Furthermore, the EU judiciary must open itself up to citizens so that – within a well-defined framework – they can call upon the Court of Justice directly). Rösler also regards new, codified European conflict of laws legislation and procedural law, which will significantly facilitate the enforcement of law before foreign courts and the EU Court of Justice, as worthwhile long-term objectives.

More information: Rösler’s study will initially be published under the title “Europäische Gerichtsbarkeit auf dem Gebiet des Zivilrechts – Strukturen, Entwicklungen und Reformperspektiven des Justiz- und Verfahrensrechts der Europäischen Union” in the Beiträge series of the Max Planck Institute for Comparative and International Private Law and by the Mohr Siebeck publishing house, Tübingen.

Provided by Max Planck Society