This article has been reviewed according to Science X's editorial process and policies. Editors have highlighted the following attributes while ensuring the content's credibility:

fact-checked

peer-reviewed publication

trusted source

proofread

Jamestown DNA helps solve a 400-year-old mystery and unexpectedly reveals a family secret

An ancient DNA (aDNA) study at the 17th-century English colony of Jamestown, Virginia, has identified two of the town's earliest settlers, and revealed an unexpected family secret.

Founded in AD 1607, Jamestown was the first permanent English settlement in the New World. Excavations at the site discovered human remains in the 1608–1616 church.

As such, it was thought that they were the bodies of some of the original colonists.

"These graves were purposely buried near the altar in the Church Chancel," says co-author of the research Dr. William Kelso, Emeritus Director of Archaeology at Jamestown Rediscovery. "This prominent location suggests the graves contained the remains of high-status individuals."

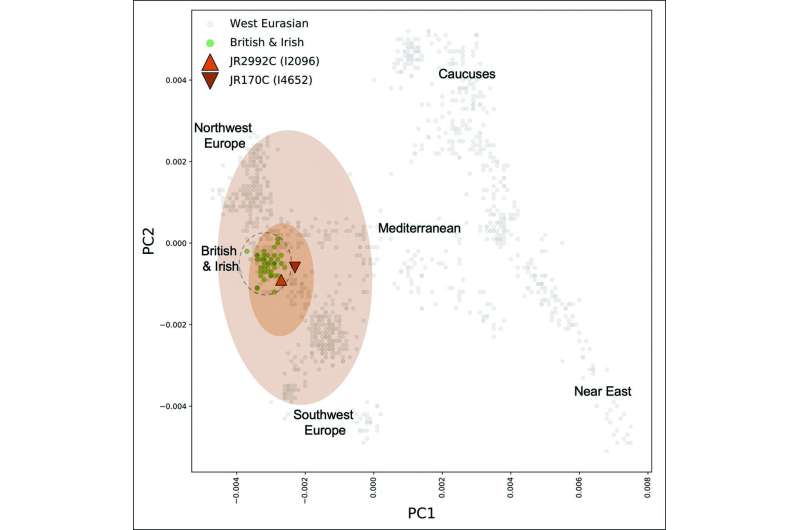

In order to determine their identities, geneticists from the Reich Lab, Harvard University, performed DNA analysis on the remains of two individuals from the graves. The team of investigators then compared these results with historical documents and osteological and archaeological evidence. Their results are published in the journal Antiquity.

"This study is the first to successfully use aDNA as a tool of identification at the colonial site of Jamestown, Virginia," states co-author Karin Bruwelheide from the Smithsonian Institution.

The skeletons' ages at death and DNA, in comparison with their burial treatment and historical records from the time, indicate that the men were Sir Ferdinando Wenman (AD 1576–1610) and Captain William West (about AD 1586–1610).

Both of these men were members of the prominent West family that included Jamestown colony's first governor: Thomas West, Third Baron De La Warr.

Importantly, this study unexpectedly revealed that these two men were related through the maternal line. This surprising finding prompted additional documentary research and the discovery of a court case over Captain West's holdings after he died. His aunt and Will benefactor strongly inferred that William was the son of Thomas' aunt Elizabeth, her sister. Elizabeth never married, meaning William was illegitimate.

Illegitimacy was taboo in the 17th century, especially within high-status families. As a result, cases of illegitimacy were often not recorded in official lineage documents. Such was the case in the West family.

Therefore, this study not only supports the identification of these men, but exposes a 400-year-old case of illegitimacy within a prominent family.

"This is the first study to demonstrate that aDNA can be used to establish historical cases of illegitimacy in high-status, 17th-century families," says Bruwelheide.

It shows how genetic evidence, when combined with other sources of information, can reveal much more than just ancestry.

"This study demonstrates the utility of combining genetic, archaeological and historical approaches to the study of the past," concludes co-author Dr. Éadaoin Harney from Harvard University.

"Despite the poor DNA preservation of the two individuals, their shared mitochondrial haplogroup helped to guide records-based historical research, ultimately leading to surprising insights into their relationship."

More information: Douglas W. Owsley et al, Historical and archaeogenomic identification of high-status Englishmen at Jamestown, Virginia, Antiquity (2024). DOI: 10.15184/aqy.2024.75

Journal information: Antiquity

Provided by Antiquity