This article has been reviewed according to Science X's editorial process and policies. Editors have highlighted the following attributes while ensuring the content's credibility:

fact-checked

peer-reviewed publication

trusted source

proofread

No two worms are alike: New study confirms that even the simplest marine organisms tend to be individualistic

Sport junkie or couch potato? Always on time or often late? The animal kingdom, too, is home to a range of personalities, each with its own lifestyle. In a study just released in the journal PLOS Biology, a team led by Sören Häfker and Kristin Tessmar-Raible from the Alfred Wegener Institute, Helmholtz Centre for Polar and Marine Research (AWI) and the University of Vienna reports on a surprising discovery: Even simple marine polychaete worms shape their day-to-day lives on the basis of highly individual rhythms.

This diversity is of interest not just for the future of species and populations in a changing environment, but also for medicine.

At first glance, the star of the new study may not seem particularly impressive: Only a few centimeters long, Platynereis dumerilii is a species of polychaete worm that can be found in temperate to tropical coastal waters around the globe; if your goal is to find outstanding animal personalities, surely there are better-suited candidates.

But that wasn't the primary goal of the study, to which experts from the AWI, the Max Perutz Labs in Vienna, the Universities of Vienna and Oldenburg, and the Katholieke Universiteit Leuven in Belgium contributed. First and foremost, the researchers were interested in the internal clocks that dictate countless organisms' daily rhythms.

"Biological timing is important at a number of levels," explains Kristin Tessmar-Raible, a biologist at the AWI. "The ecological ties between species depend just as much on it as they do on biochemical processes at the cellular level."

But how do organisms' internal clocks react when human beings warm the climate or use artificial light to turn night into day?

"When it comes to marine organisms, we still know very little," says Sören Häfker, the study's main author. In this regard, rhythms are especially important in their lives: temperature, available light and food, and various other factors change throughout the day, and the organisms have to respond accordingly. They adapt their behavior, metabolism, and genetic activity to these external rhythms.

However, it remains unclear whether they'll be equally successful at doing so in the future. And when their internal clocks no longer match their environment, it can become a matter of survival.

"As such, we need a much better understanding of how the rhythms of the oceans are changing and what it will mean for individual species and populations," the biologist stresses—which means there is a wealth of reasons to take a closer look at the daily behavior of Platynereis dumerilii. In fact, for chronobiology, which focuses on organisms' internal clocks, this distant relative of the dew worm has become one of the most important model species.

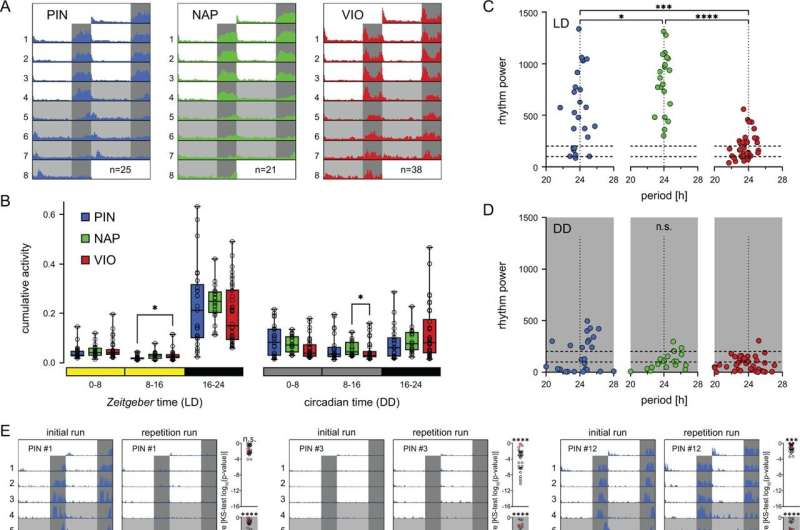

In past experiments, the team had noticed how the worms had quite disparate daily rhythms. Among human beings, it's a familiar phenomenon; early birds rarely turn into night owls, and vice versa. But what about in marine polychaete worms? Are their behavioral differences just random variations or do they also have a personal tact?

To find out, the group systematically observed the worms' daily activities when there was a new moon. They saw that some individuals became active at exactly the same time every night. In turn, others appeared to be arrhythmic "couch potatoes" that were only occasionally active—plus, there were various "shades of gray" between these two extremes.

When the same worms were observed again several weeks later, their behavior remained largely unchanged: once a couch potato, always a couch potato.

"We were very surprised to see how reproducible the individual behavioral rhythms were," says Tessmar-Raible. "This shows us that even worms have tiny, rhythmic personalities, so to speak."

More individuality equals more resiliency

To gain further insights into these behavioral differences, the group systematically compared the genetic activity in the heads of worms prone to particularly rhythmic and arrhythmic behavior. Surprisingly, they found that the daily internal clock worked perfectly fine in all specimens, even the arrhythmic "couch potatoes," and that the number of genes with rhythmic activity was nearly as high as in the "punctual" worms.

The wide range of strategies they employ could offer the worms an evolutionary edge, as the experts surmise. After all, they live in a coastal environment with highly variable conditions; as such, lifestyle A might be the best choice for a given spot, while not far away, lifestyle B might be a better fit. In addition, this form of individuality could make them more resilient to major anthropogenic changes—in a transforming world, this diversity increases the chances of at least some worms being able to cope with their new circumstances.

But the study doesn't just offer new insights into marine rhythms; it also underscores the fact that the processes at work within a given organism aren't necessarily reflected in its behavior: even among the couch potato worms, the genetic activity follows a daily rhythm, even if it's not externally recognizable. And that's likely true not just for worms, but for human beings as well.

"That's why such findings are also exciting for fields like chronomedicine," says Tessmar-Raible.

In recent years, there have been intensified and successful efforts to bear patients' individual daily rhythms in mind in the context of treating them. But, just as with the worms observed, they consist of various components, ranging from behavior to genetic activity, which can react differently to medications and the timing of when they are administered.

Accordingly, especially when it comes to human beings, it is important for chronomedical analyses to consider several different levels. If even worms can be so individualistic, our species is likely no exception.

More information: N. Sören Häfker et al, Molecular circadian rhythms are robust in marine annelids lacking rhythmic behavior, PLOS Biology (2024). DOI: 10.1371/journal.pbio.3002572

Journal information: PLoS Biology

Provided by Alfred Wegener Institute