This article has been reviewed according to Science X's editorial process and policies. Editors have highlighted the following attributes while ensuring the content's credibility:

fact-checked

trusted source

proofread

New toolkit helps scientists study natural cell death

New research from the Weeks Lab in the Department of Biochemistry opens the door for scientists to explore cell death, a critical biochemical process, with greater ease.

When deciduous trees drop their leaves each year as the temperatures cool, it is not a sign of organismal death but rather an indication of a healthy tree, full of life. So, too, the orderly and intentional death of cells, or apoptosis, is a sign of good human health.

Cells undergo apoptosis for many different reasons, including eliminating extra immune cells that remain after fighting off an infection or stopping uncontrolled cell division in its tracks.

A cell undergoing apoptosis cuts apart proteins, which are formed from long chains of amino acids called peptides, at specific cleavage sites. The result is new, shorter peptide chains that can stop certain cellular functions or even create the potential for new functions. This process of breaking apart proteins, known as proteolysis, is highly regulated. Through proteolysis, a cell's death is controlled, which helps prevent damage to neighboring cells.

When proteolytic pathways such as apoptosis do not occur as they are supposed to, there can be serious consequences. Cancerous tumors, for example, can form when unhealthy cells fail to undergo apoptosis and instead continue to proliferate.

Scientists lack the full picture about where proteins are cleaved, how cells know where to cut proteins, and how each cut alters protein function. That's because until now, the available tools to study proteolytic pathways were expensive and required specialized expertise to synthesize probes that could recognize cleavage sites chemically. This has limited the tools' access to many scientists.

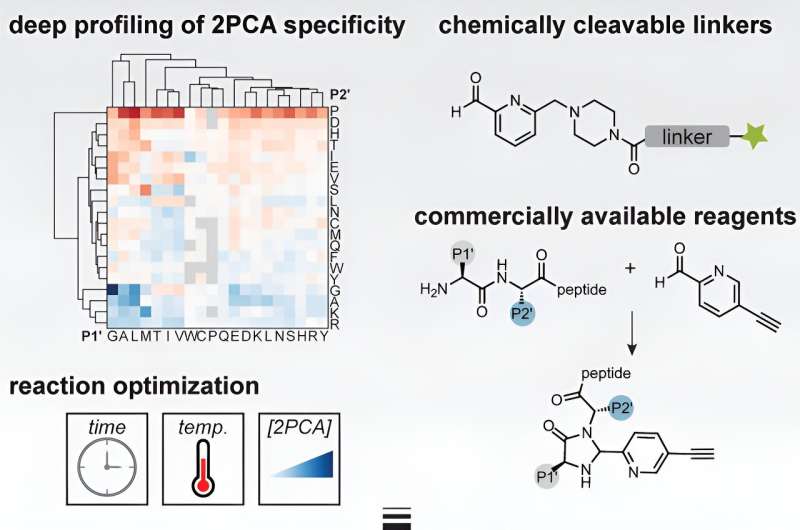

Researchers in the Weeks Lab have developed a new toolbox for scientists studying protein cleavage sites associated with apoptosis and other proteolytic pathways. Taking advantage of the unique biochemical properties of protein fragments, their tool uses less expensive, more efficient, off-the-shelf chemical compounds to help identify sites where proteins were cut.

When a protein is cut, one fragment inherits the original starting point, while the other must establish a new starting point. These new starting points have a uniquely strong affinity for Vitamin B7, also known as biotin. The Weeks Lab used biotin as glue to attach chemical compounds to the ends of protein fragments, allowing them to isolate the fragments.

From there, the fragments can be analyzed to learn more about how cells identify cleavage sites and how a cut may alter a protein's function. This information may offer new insight into the impacts on human health when these pathways go awry.

The research is published in the journal Cell Chemical Biology.

More information: Haley N. Bridge et al, An N terminomics toolbox combining 2-pyridinecarboxaldehyde probes and click chemistry for profiling protease specificity, Cell Chemical Biology (2023). DOI: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2023.09.009

Provided by University of Wisconsin-Madison