This article has been reviewed according to Science X's editorial process and policies. Editors have highlighted the following attributes while ensuring the content's credibility:

fact-checked

reputable news agency

proofread

What are attoseconds? Nobel-winning physics explained

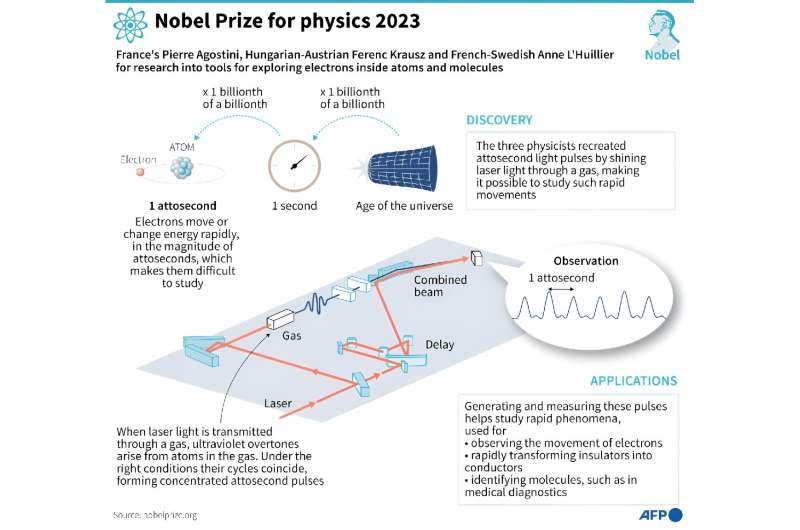

The Nobel Physics Prize was awarded on Tuesday to three scientists for their work on attoseconds, which are almost unimaginably short periods of time.

Their work using lasers gives scientists a tool to observe and possibly even manipulate electrons, which could spur breakthroughs in fields such as electronics and chemistry, experts told AFP.

How fast are attoseconds?

Attoseconds are a billionth of a billionth of a second.

To give a little perspective, there are around as many attoseconds in a single second as there have been seconds in the 13.8-billion year history of the universe.

Hans Jakob Woerner, a researcher at the Swiss university ETH Zurich, told AFP that attoseconds are "the shortest timescales we can measure directly".

Why do we need such speed?

Being able to operate on this timescale is important because these are the speeds at which electrons—key parts of an atom—operate.

For example, it takes electrons 150 attoseconds to go around the nucleus of a hydrogen atom.

This means the study of attoseconds has given scientists access to a fundamental process that was previously out of reach.

All electronics are mediated by the motion of electrons—and the current "speed limit" is nanoseconds, Woerner said.

If microprocessors were switched to attoseconds, it could be possible to "process information a billion times faster," he added.

How do you measure them?

Franco-Swede physicist Anne L'Huillier, one of the three new Nobel laureates, was the first to discover a tool to pry open the world of attoseconds.

It involves using high-powered lasers to produce pulses of light for incredibly short periods.

Franck Lepine, a researcher at France's Institute of Light and Matter who has worked with L'Huillier, told AFP it was like "cinema created for electrons".

He compared it to the work of pioneering French filmmakers the Lumiere brothers, "who cut up a scene by taking successive photos".

John Tisch, a laser physics professor at Imperial College London, said that it was "like an incredibly fast, pulse-of-light device that we can then shine on materials to get information about their response on that timescale".

How low can we go?

All three of Tuesday's laureates at one point held the record for shortest pulse of light.

In 2001, French scientist Pierre Agostini's team managed to flash a pulse that lasted just 250 attoseconds.

L'Huillier's group beat that with 170 attoseconds in 2003.

In 2008, Hungarian-Austrian physicist Ferenc Krausz more than halved that number with an 80-attosecond pulse.

The current holder of the Guinness World Record for "shortest pulse of light" is Woerner's team, with a time of 43 attoseconds.

The time could go as low as a few attoseconds using current technology, Woerner estimated. But he added that this would be pushing it.

What could the future hold?

Technology taking advantage of attoseconds has largely yet to enter the mainstream, but the future looks bright, the experts said.

So far, scientists have mostly only been able to use attoseconds to observe electrons.

"But what is basically untouched yet—or is just really beginning to be possible—is to control" the electrons, to manipulate their motion, Woerner said.

This could lead to far faster electronics as well as potentially spark a revolution in chemistry.

"We would not be limited to what molecules naturally do," but instead could "tailor them according to need," Woerner said.

So-called "attochemistry" could lead to more efficient solar cells, or even the use of light energy to produce clean fuels, he added.

© 2023 AFP