June 30, 2023 report

This article has been reviewed according to Science X's editorial process and policies. Editors have highlighted the following attributes while ensuring the content's credibility:

fact-checked

peer-reviewed publication

trusted source

proofread

Smarter men are putting off having children until later in life but are still having more children, say economists

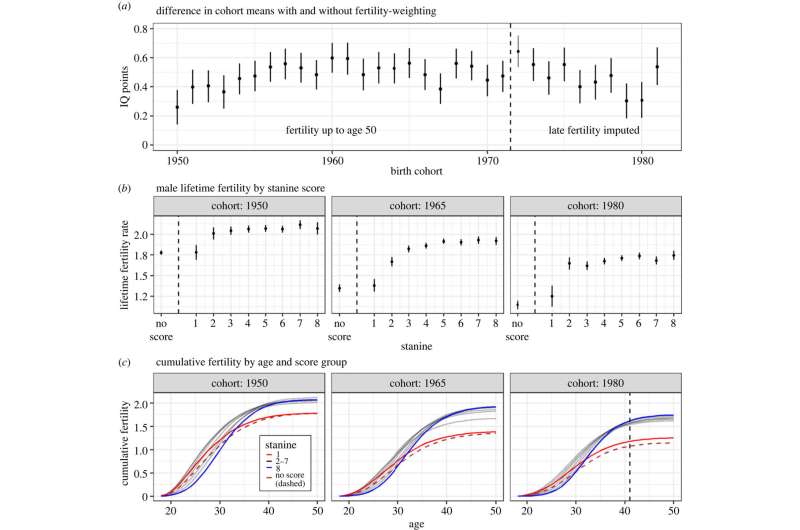

A pair of economists at the Ragnar Frisch Center for Economic Research in Norway has found that men who score higher on IQ tests tend to put off having children longer than men who score lower—and yet they still mange to have more children than their lower-scoring associates. In their study, reported in the journal Biology Letters, Bernt Bratsberg and Ole Rogeberg analyzed population data for males in Norway living between the years 1950 to 1981.

In their study, the researchers included more than 900,000 Norwegian males, all of whom had undergone military conscription IQ tests as teenagers. They found that men scoring in the top 20% on the IQ tests waited on average until they were 27 years old before having their first child—and they had on average 1.8 offspring. They note that it is likely that IQ plays an indirect role in childbearing for men in Norway.

They point out, for example, that men who score well on their IQ test tend to be more likely to go to college, which can lead to delayed parenting, as can beginning a career at a later age, after college, than men who do not attend college. And men who go to college tend to make more money later in life than men who do not, allowing them to afford the costs associated with raising children.

Bratsberg and Rogeberg also note that regardless of the economic reasons for the differences in having children, there remain systematic differences in fertility and timing due to cognitive differences in men in Norway, with high-scoring men clearly delaying having children and low-scoring men having children sooner, but having fewer of them. These trends remained stable over time.

Prior research has shown that couples having children later in life can be problematic on a socioeconomic scale—sperm count and delivery issues become more of an issue as a man ages, as does a man's ability to physically care for a child. Also, children born to men age 45 and up have a much higher risk of fathering children with autism spectrum disorder and ADHD. Also, the risk of miscarriage goes up for women who deliver babies fathered by older men.

More information: Bernt Bratsberg et al, Stability and change in male fertility patterns by cognitive ability across 32 birth cohorts, Biology Letters (2023). DOI: 10.1098/rsbl.2023.0172

Journal information: Biology Letters

© 2023 Science X Network