How equal charges in enzymes control biochemical reactions

It is well known in physics and chemistry that equal charges repel each other, while opposite charges attract. It was long assumed that this principle also applies when enzymes—the biological catalysts in all living organisms—form or break chemical bonds. It was thought that enzymes place charges in their "active centers," where the chemical reactions actually take place, in such a way that they repel similar charges from the other molecules around them. This concept is known as "electrostatic stress." For example, if the substrate (the substance upon which the enzyme acts) carries a negative charge, the enzyme could use a negative charge to "stress" the substrate and thus facilitate the reaction. However, a new study by the University of Göttingen and the Max Planck Institute for Multidisciplinary Sciences in Göttingen has now shown that, contrary to expectations, two equal charges do not necessarily lead to repulsion, but can cause attraction in enzymes. The results were published in the journal Nature Catalysis.

The team investigated a well-known enzyme that has been studied extensively and is a textbook example of enzyme catalysis. Without the enzyme, the reaction is extremely slow: in fact, it would take 78 million years for half of the substrate to react. The enzyme accelerates this reaction by 1017 times, simply by positioning negative and positive charges in the active center. Since the substrate contains a negatively charged group that is split off as carbon dioxide, it was assumed for decades that the negative charges of the enzyme serve to stress the substrate, which is also negatively charged, and accelerate the reaction. However, this hypothetical mechanism remained unproven because the structure of the reaction was too fast to be observed.

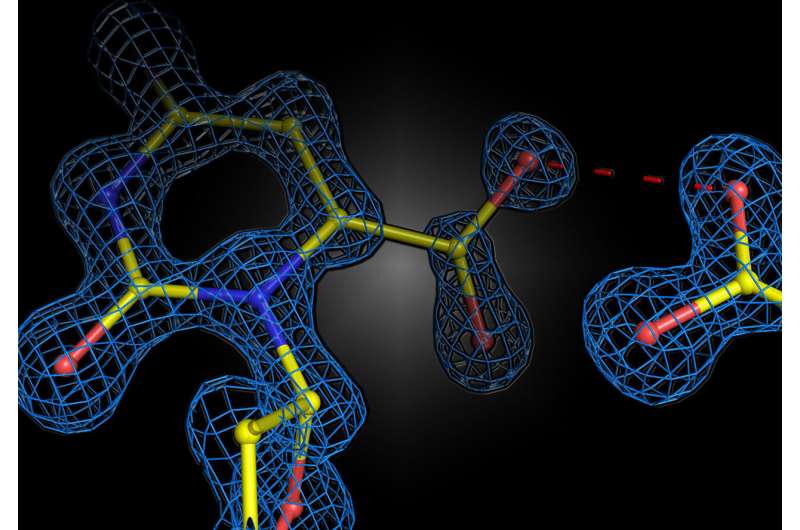

Professor Kai Tittmann's group at the Göttingen Center for Molecular Biosciences (GZMB) has now succeeded for the first time in using protein crystallography to obtain a structural snapshot of the substrate shortly before the chemical reaction. Unexpectedly, the negative charges of enzyme and substrate did not repel each other. Instead, they shared a proton, which acted like a kind of molecular glue in an attractive interaction. "The question of whether two equal charges are friends or foes in the context of enzyme catalysis has long been controversial in our field, and our study shows that the basic principles of how enzymes work are still a long way from being understood," says Tittmann. The crystallographic structures were analyzed by quantum chemist Professor Ricardo Mata and his team from Göttingen University's Institute of Physical Chemistry. "The additional proton, which has a positive charge, between the two negative charges is not only used to attract the molecule involved in the reaction, but it triggers a cascade of proton transfer reactions that further accelerate the reaction," Mata explains.

"We believe that these newly described principles of enzyme catalysis will help in the development of new chemical catalysts," says Tittmann. "Since the enzyme we studied releases carbon dioxide, the most important greenhouse gas produced by human activities, our results could help develop new chemical strategies for carbon dioxide fixation."

More information: Sören Rindfleisch et al, Ground-state destabilization by electrostatic repulsion is not a driving force in orotidine-5′-monophosphate decarboxylase catalysis, Nature Catalysis (2022). DOI: 10.1038/s41929-022-00771-w

Journal information: Nature Catalysis

Provided by University of Göttingen