When debris disaster strikes

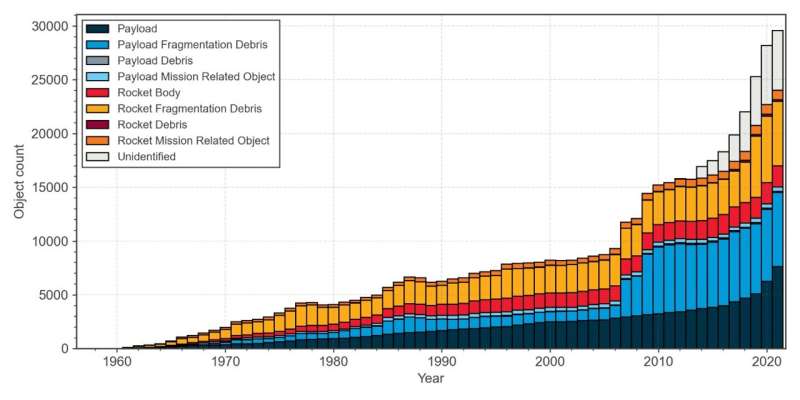

In 2021 so far, some 2467 new objects large enough to be tracked have been added to world catalogs of orbital objects, out of which 1493 are new satellites and the rest are debris. While new objects are added, others are dragged down to Earth by the atmosphere where they safely burn up, resulting in a net increase of at least 1387 trackable objects between 2020 and 2021.

In addition, an estimated 1500 new objects—an increase of about 5% with respect to the total population—were added just this week, meaning the risk to missions must be reassessed.

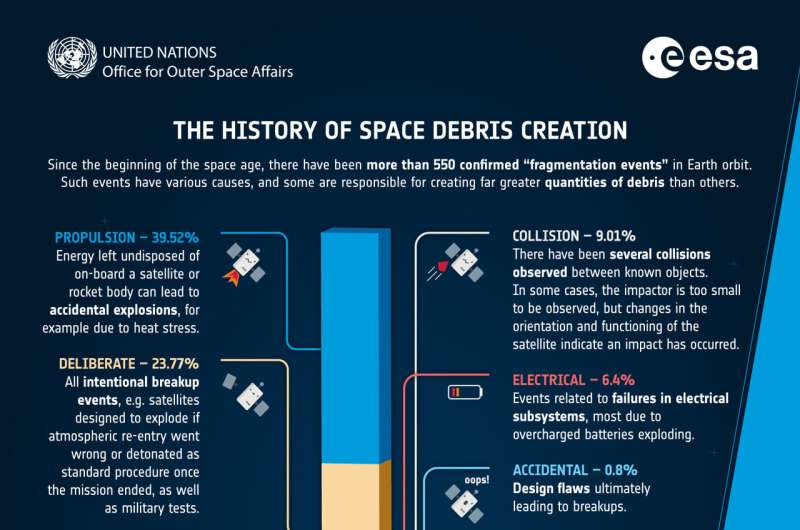

Every now and then, an event occurs in Earth orbit that generates large quantities of new space debris. Accidental explosions caused by leftover fuel onboard satellites and rockets have created the greatest number of debris objects, but second in line are deliberate breakup events.

Some 36,000 objects larger than a tennis ball are orbiting Earth, and only 13% of these are actively controlled. The rest comprise space debris, the direct result of 'fragmentation events' of which roughly 630 are known to have occurred to date.

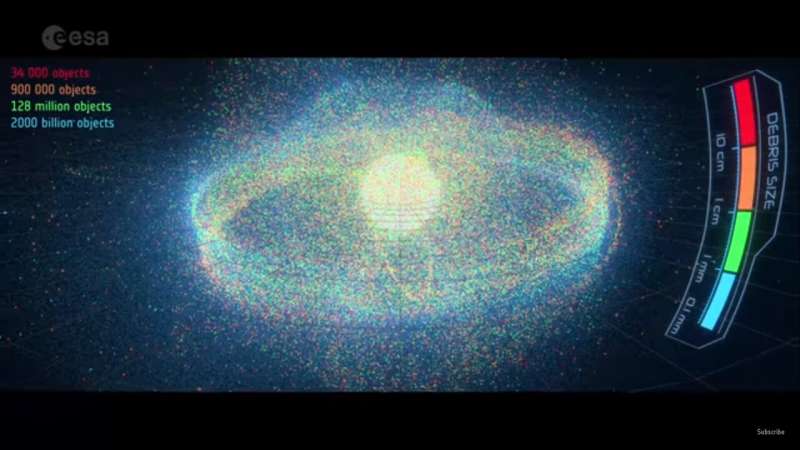

Based on observations of larger objects together with statistical models (for those objects too small to be observed with telescopes on Earth), ESA estimates there are in orbit today:

- 36,500 objects greater than 10 cm in size

- 1,000,000 objects from 1 cm to 10 cm

- 330 million objects from 1 mm to 1 cm

After each new fragmentation event, ESA's Space Debris Office begins its analysis. What happened? How will this shape the debris environment, now and in the future? What has been the change in collision risk to active satellites and spacecraft in orbit? Which altitudes and orbits are the most affected?

New objects tracked

In 2021 so far, some 2,467 new objects large enough to be tracked have been added to world catalogs of orbital objects, out of which 1,493 are new satellites and the rest are debris. While new objects are added, others are dragged down to Earth by the atmosphere where they safely burn up, resulting in a net increase of at least 1387 trackable objects between 2020 and 2021.

In addition, an estimated 1500 new objects—an increase of about 5% with respect to the total population—were added just this week.

Because debris objects travel at high velocities, a collision with a fragment as small as just 1 cm in diameter can generate the same amount of destructive energy as a small car crashing at 40 km/h.

While the smallest, sub-millimeter-sized debris particles may only degrade the functioning of a satellite upon impact, 'larger' pieces—in the centimeter range—can cause complete destruction.

Earth's atmosphere can cause orbital objects to re-enter over time and burn up. The higher the orbital altitude, the thinner the atmosphere, and so the longer objects will naturally stay in space. In altitudes above 600 km, the natural 'residence time' in space for such objects is typically more than 25 years.

ESA's Earth Observation missions, which orbit in this region, have each had to perform two 'collision avoidance maneuvers' on average per year, to dodge oncoming debris.

Reassessing risk

After fragmentation events, such as one that happened this week, the risk to missions must be reassessed.

"This major fragmentation event will not only more than double the long-term collision avoidance needs for missions in orbits with similar altitudes, but will furthermore significantly increase the probability of potentially mission-terminating collisions at lower altitudes," says Holger Krag, Head of ESA's Space Safety Programme.

International cooperation

Space debris are constantly monitored by the US space surveillance network, and ESA's space debris experts use this and other monitoring data to improve and update models to better understand the evolving debris environment.

By performing daily collision risk analyses and creating models that predict the future position and density of debris objects at various altitudes, the team can advise satellite operators on how best to keep their missions safe.

Keeping space highways safe

The United Nations has set out guidelines to reduce the growing amount of space debris in orbit. Experts from ESA's Space Debris Office have contributed to these guidelines and routinely advise on how to implement them for ESA missions.

Furthermore, as part of the Agency's space safety and security activities, ESA is working to keep Earth's commercially and scientifically vital orbital environment as debris-free as possible and to pioneer an eco-friendly approach to space activities.

ESA is the first space agency to adopt the ambitious target of inverting Europe's contribution to space debris by 2030, directly tackling the issue of space debris by advancing the technology needed to maintain a clean space environment. ESA has initiated the first active debris-removal mission to be launched in 2025 to demonstrate the ability to remove debris from an orbit at 700 km.

But as the 'New Space' era beckons, and large constellations comprising thousands of satellites start to be launched, much more needs to be done to ensure Earth's space environment is used sustainably for future generations.

ESA accelerates the protection of our space investment

The current situation calls for new technology that will allow regulators to consider a systematic implementation of zero-debris policies. A new European commercial capability needs to be forged to provide innovative in-orbit services, such as refueling, refurbishing and extending the life of existing missions. This will lead to a 'circular economy' in space.

To ensure safe access to space, high-precision position information on all orbital objects must become available, and automated coordination between spacecraft operators must be implemented. Novel technology will be required for these ambitious steps, which are proposed as part of the new 'Protect' Accelerator, one of three currently being defined to help shape Europe's future in space.

Space technology, and the multitude of applications that flow from it, is vital to Europe's economy. Ensuring the safety of our space infrastructure and investments, and therefore Europe's non-dependent use of space, is vital for safeguarding businesses, economies and ultimately our way of life.

Provided by European Space Agency