Marine microfibres: less plastic than predicted

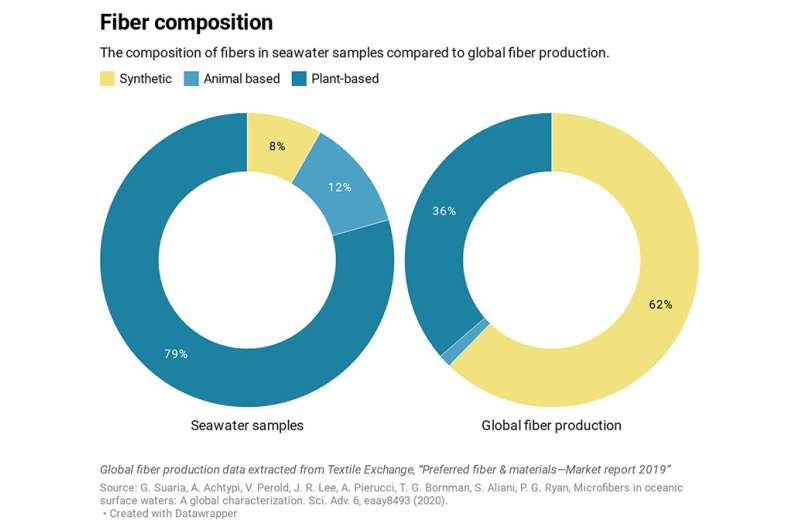

Microfibers are fine strands of thread used to make clothing, carpeting and household items like mops. They are found in the air we breathe, the water we drink, and throughout the world's oceans. Natural, rather than synthetic, microfibers, though, make up the majority of those found in the ocean's surface waters—despite the fact that currently two-thirds of all human-produced fibers are synthetic.

Over the course of two years and five expeditions, University of Cape Town's (UCT) Professor Peter Ryan and his team gathered 916 seawater samples from oceans around the world.

"Some of these were collected as part of the Antarctic Circumnavigation Expedition, which took place from 2016 to 2017. Others were collected by researchers at sites in the Mediterranean, and Indian and Atlantic oceans," explains Ryan, director of the FitzPatrick Institute of African Ornithology based at UCT.

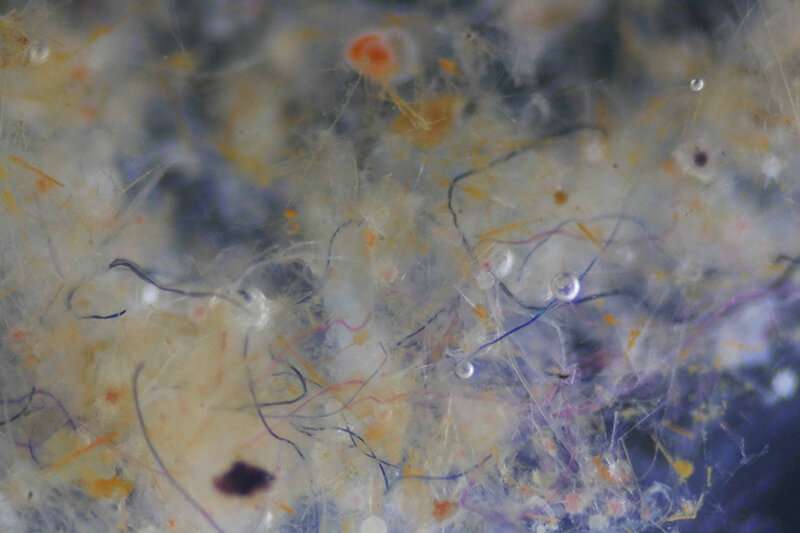

In most cases, the researchers collected a sample of 10 liters of sea water using a metal bucket lowered from the ship's bow during navigation. They then filtered the water in a laboratory and counted and analyzed all the fibers.

In general, each 10-liter sample of sea water contained 10 to 20 fibers, with a maximum of up to 500 fibers counted in a single sample.

Only 8% of the fibers in these samples were microplastics. The rest, more than 90%, were plant or animal-based materials, like cotton, wool and other celluloses, such as linen and flax.

The painstaking work of identifying thousands of fibers was conducted over the course of a year by Dr. Giuseppe Suaria, an ocean scientist based at the Italian Institute of Marine Science and the lead author of the research published today in Science Advances.

Synthetic fiber shortage

During 2018, the world produced 107 million tons of fiber—or the weight of more than 1 million Eiffel Towers. Of this, 62% was synthetic, with the majority produced from polyester plastics.

"Our results showed that while it is true that textile fibers are ubiquitous in our oceans, there is a striking shortage of synthetic fibers," says Ryan.

What accounts for this mismatch?

According to Ryan there are several possible explanations, but at this point there is insufficient information to understand the phenomenon.

"It may be that natural fibers are not degrading in the marine environment due to dyes, coatings or chemical additives. Or, it could be that synthetic fabrics shed and release less fibers into the environment (for example, when being laundered) compared to natural fabrics."

Ryan explains that they could be seeing more natural fibers in the ocean because they have had more time to accumulate, given their historical dominance in industry before the advent of synthetic polymers.

To be certain, Ryan says they would need to do more research to better understand the rate of decay of natural and synthetic fibers across a range of sea temperatures. Only then we can understand the dynamics at play in the degradation of these materials in our oceans and their impact on living organisms.

Seeing plastic pollution in context

While this is a surprising outcome, according to Ryan, it was not completely unexpected.

"Previous studies showed similar dominance of natural fibers in other environments, including rivers, the atmosphere and sea-ice. However, the considerable media attention on microplastic pollution in the ocean makes this an important finding because it means we need to rethink estimates of microplastic abundance at sea," he says.

The impacts of microfiber ingestion on marine organisms are poorly understood—irrespective of whether they are natural or synthetic in origin. Some lab studies have indicated adverse impacts, but not at the low concentrations currently found in the environment.

For larger animals, such as the seabirds Ryan studies, microfibers probably pass through the digestive tract quite rapidly, and thus have less of an impact than do larger plastic fragments, which might be retained for months by some birds.

And while it is a hopeful discovery that there are fewer microplastics in surface waters than many would have predicted, Ryan believes these results must be viewed in the light of the wider and immense human impact on the oceans.

"We must also reconsider the impact of natural fibers—as well as synthetic ones—by looking into ways for fabrics to shed less overall, rather than swapping out synthetic for natural fabrics," says Ryan.

More information: Giuseppe Suaria et al. Microfibers in oceanic surface waters: A global characterization, Science Advances (2020). DOI: 10.1126/sciadv.aay8493

Journal information: Science Advances

Provided by University of Cape Town