October 18, 2019 feature

Quantum spacetime on a quantum simulator

Quantum simulation plays an irreplaceable role in diverse fields, beyond the scope of classical computers. In a recent study, Keren Li and an interdisciplinary research team at the Center for Quantum Computing, Quantum Science and Engineering and the Department of Physics and Astronomy in China, U.S. Germany and Canada. Experimentally simulated spin-network states by simulating quantum spacetime tetrahedra on a four-qubit nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) quantum simulator. The experimental fidelity was above 95 percent. The research team used the quantum tetrahedra prepared by nuclear magnetic resonance to simulate a two-dimensional (2-D) spinfoam vertex (model) amplitude, and display local dynamics of quantum spacetime. Li et al. measured the geometric properties of the corresponding quantum tetrahedra to simulate their interactions. The experimental work is an initial attempt and a basic module to represent the Feynman diagram vertex in the spinfoam formulation, to study loop quantum gravity (LQG) using quantum information processing. The results are now available on Communication Physics.

Classical computers cannot study large quantum systems despite successful simulations of a variety of physical systems. The systematic constraints of classical computers occurred when the linear growth of quantum system sizes corresponded to the exponential growth of the Hilbert Space, a mathematical foundation of quantum mechanics. Quantum physicists aim to overcome the issue using quantum computers that process information intrinsically or quantum-mechanically to outperform their classical counterparts exponentially. In 1982, Physicist Richard Feynman defined quantum computers as quantum systems that can be controlled to mimic or simulate the behaviour or properties of relatively less accessible quantum systems.

In the present work, Li et al. used nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) with a high controllable performance on the quantum system to develop simulation methods. The strategy facilitated the presentation of quantum geometries of space and spacetime based on the analogies between nuclear spin states in NMR samples and spin-network states in quantum gravity. Quantum gravity aims to unite the Einstein gravity with quantum mechanics to expand our understanding of gravity to the Planck scale (1.22 x 1019 GeV). At the Planck scale (magnitudes of space, time and energy) Einstein gravity and the continuum of spacetime breakdown can be replaced via quantum spacetime. Research approaches toward understanding quantum spacetimes are presently rooted in spin networks (a graph of lines and nodes to represent the quantum state of space at a certain point in time), which are an important, non-perturbative framework of quantum gravity.

In 1971, physicist Roger Penrose proposed spin networks motivated by the twistor theory with subsequent applications to loop quantum gravity (LQG). The spin networks were quantum states representing fundamentally discrete quantum geometries of space at the Planck scale. In the present study, the research team represented the spin network using a graph with links and nodes colored by spin halves. For example, any node with edges corresponded to a geometry and therefore a graph containing four-valent nodes corresponded to quantum tetrahedron geometry.

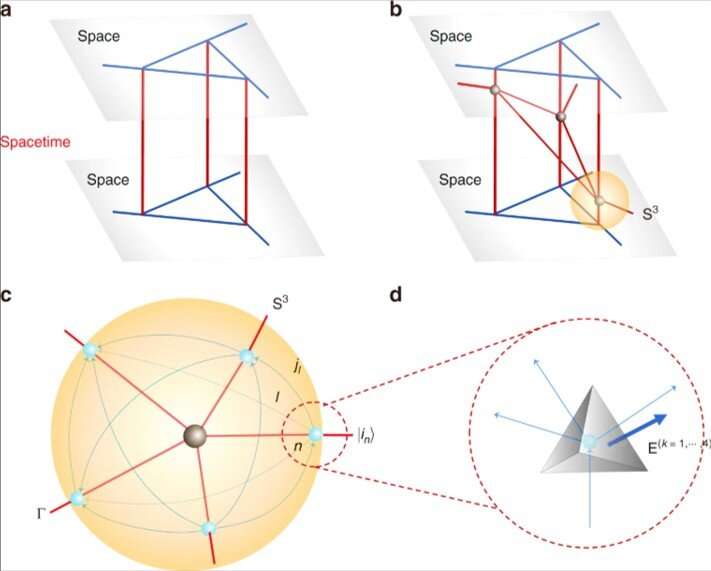

The research team developed a "network" containing a number of three-dimensional (3-D) world sheets (2-D surfaces) and their intersections. They showed that each vertex where the surfaces met, led to a quantum transition that changed the spin network to represent local dynamics of quantum geometry. Much like Feynman diagrams (schematic representations of mathematical expressions describing the behavior of subatomic particles), quantum spacetimes encoded the transition amplitudes and spinfoam amplitudes between the initial and final spin networks. The quantum spacetimes and spinfoam amplitudes developed in the study provided a consistent and promising approach to quantum gravity. Li et al. featured the NMR simulation by the capability to control individual qubits with high precision. The quantum tetrahedra and vertex amplitudes served as building blocks of LQG (loop quantum gravity) to open a new window to include LQG in quantum experiments.

The scientists first derived equations to describe a quantum tetrahedron within a spin network. In a schematic 3+1-dimensional dynamic quantum spacetime model, they demonstrated an atom as a 3-sphere enclosing a portion of the quantum spacetime surrounding a vertex. The team modeled the boundary of the enclosed quantum spacetime precisely as a spin network and showed the possibility of simulating large quantum spacetimes with many vertices by quantum gluing the atoms. The resulting structure resembled vertex amplitude of quantum spacetime similar to previously developed Ooguri's topological lattice models in four dimensions. The researchers showed LQG to identify quantum tetrahedron geometries with the quantum angular momenta. The identification allowed them to simulate quantum geometries with quantum registers (quantum mechanical analogue of a classical processor register). In general, a quantum register can be mathematically achieved using tensor products.

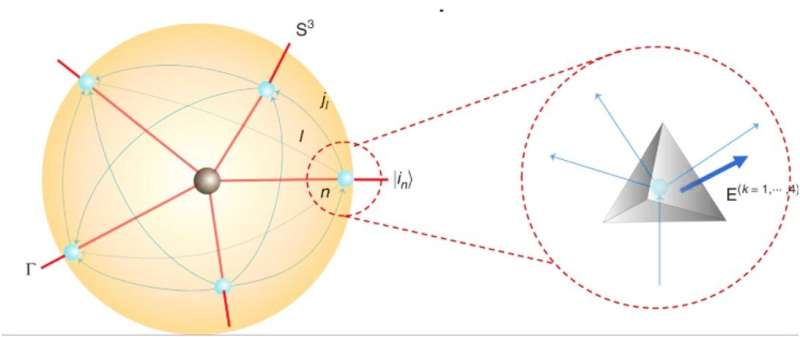

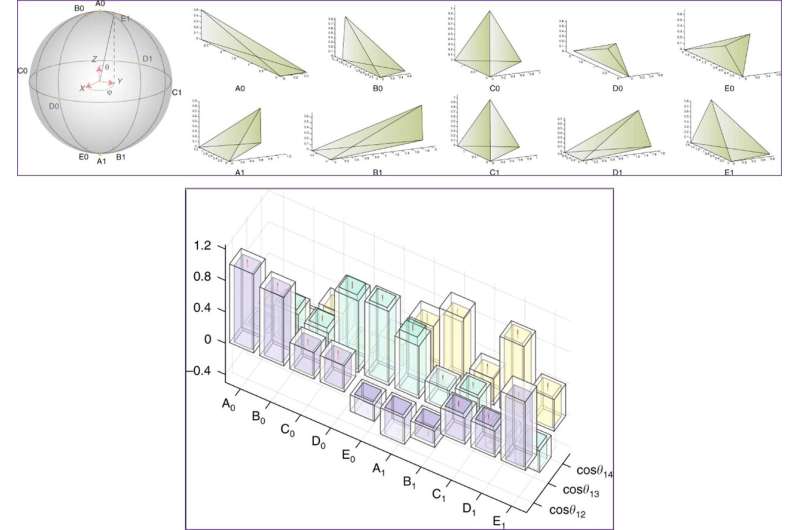

During the experiments, Li et al. simulated 10 quantum tetrahedra by preparing the corresponding invariant-tensor states. They labeled these states using 10 colored points on the Bloch sphere (geometrical representation) and conducted the experiments on a 700-MHz DRX Bruker spectrometer at room temperature. For all experiments, the research team used the crotonic acid molecule with four 13C nuclei suited for the four-qubit system. The scientists developed the experimental system to prepare quantum tetrahedra and simulate its local dynamics in three parts.

- For state preparation, first they initialized the entire system to a pseudo-pure state. They obtained a fidelity above 99 percent using the spatial average method. Then they drove the system into 10 invariant-tensor states or transformations, which they implemented using 10 shaped pulses of 20 ms.

- Next, for geometry measurements, the team presented the measured geometry properties using a 3-D histogram. The experimental uncertainty at this point resulted from the NMR spectrum-fitting process. The coincidence between experimental and theoretical simulations implied that the invariant tensor states prepared in the experiments matched the building blocks—quantum tetrahedra.

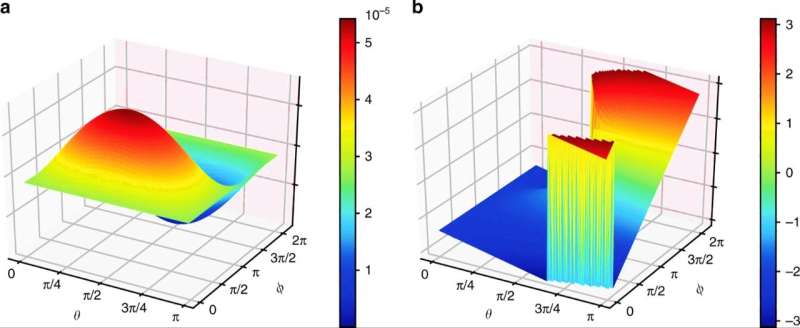

- During amplitude simulation, the spin-network states served as the boundary data of 3+1-dimensional quantum spacetime. The vertex amplitude defined in the study determined the spinfoam amplitude and described the local dynamics of quantum gravity in 4-D quantum spacetime, to display the properties of these boundary data.

In order to obtain the vertex amplitudes, the researchers calculated the inner products between five different quantum tetrahedron states. Ideally, the researchers could have used a 20-qubit quantum computer, establishing two-qubit maximally entangled states between two arbitrary tetrahedra. However, since a quantum computer of such dimensions is presently beyond commercialized cutting-edge technology, the researchers alternately conducted full tomography of the state preparation to obtain information of quantum tetrahedron states. When the scientists calculated the fidelities between the experimental quantum tetrahedron states and theory, the results were well above 95 percent. Using the quantum tetrahedra, the research team simulated the vertex amplitude. They compared the results between the experiment and the numeric simulation among all five tetrahedra. Accordingly, saddle points of the amplitude in the experiments occurred where the five interacting tetrahedra demonstrated a simple geometric meaning as they glued to form a geometric four-simplex.

In this way, Keren Li and co-workers used a quantum register in the NMR system to create 10 invariant-tensor states to represent 10 quantum tetrahedra. They achieved a fidelity above 95 percent and subsequently measured the dihedral angles (two plane faces) of the model. They considered the spectrum-fitting errors and geometrical identification to understand the success in simulating quantum tetrahedra in the study. The new research work presented a first-step to explore spin-network states and spinfoam amplitudes using a quantum simulator. The accompanying work also demonstrated valid experiments to study LGQ.

More information: Keren Li et al. Quantum spacetime on a quantum simulator, Communications Physics (2019). DOI: 10.1038/s42005-019-0218-5

Richard P. Feynman. Simulating physics with computers, International Journal of Theoretical Physics (2007). DOI: 10.1007/BF02650179

S. Lloyd. Universal Quantum Simulators, Science (2006). DOI: 10.1126/science.273.5278.1073

Journal information: Communications Physics , Science

© 2019 Science X Network