How the building blocks of life may form in space

In a laboratory experiment that mimics astrophysical conditions, with cryogenic temperatures in an ultrahigh vacuum, scientists used an electron gun to irradiate thin sheets of ice covered in basic molecules of methane, ammonia and carbon dioxide. These simple molecules are ingredients for the building blocks of life. The experiment tested how the combination of electrons and basic matter leads to more complex biomolecule forms—and perhaps eventually to life forms.

"You just need the right combination of ingredients," author Michael Huels said. "These molecules can combine, they can chemically react, under the right conditions, to form larger molecules which then give rise to the bigger biomolecules we see in cells like components of proteins, RNA or DNA, or phospholipids."

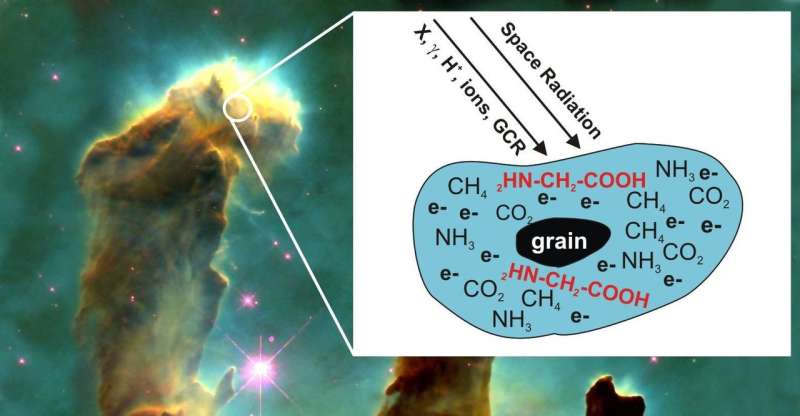

The right conditions, in space, include ionizing radiation. In space, molecules are exposed to UV rays and high-energy radiation including X-rays, gamma rays, stellar and solar wind particles and cosmic rays. They are also exposed to low-energy electrons, or LEEs, produced as a secondary product of the collision between radiation and matter. The authors examined LEEs for a more nuanced understanding of how complex molecules might form.

In their paper, published in the Journal of Chemical Physics, the authors exposed multilayer ice composed of carbon dioxide, methane and ammonia to LEEs and then used a type of mass spectrometry called temperature programmed desorption (TPD) to characterize the molecules created by LEEs.

In 2017, using a similar method, these researchers were able to create ethanol, a nonessential molecule, from only two ingredients: methane and oxygen. But these are simple molecules, not nearly as complex as the larger molecules that are the stuff of life. This new experiment has yielded a molecule that is more complex, and is essential for terrestrial life: glycine.

Glycine is an amino acid, made of hydrogen, carbon, nitrogen and oxygen. Showing that LEEs can convert simple molecules into more complex forms illustrates how life's building blocks could have formed in space and then arrived on Earth from material delivered via comet or meteorite impact.

In their experiment, for each 260 electrons of exposure, one molecule of glycine was formed. Seeking to know how realistic this rate of formation was in space, not just in the laboratory, the researchers extrapolated out to determine the probability that a carbon dioxide molecule would encounter both a methane molecule and ammonia molecule and how much radiation they, together, might encounter.

"You have to remember—in space, there is a lot of time," Huels said. "The idea was to get a feel for the probability: Is this a realistic yield, or is this a quantity that is completely nuts, so low or so high that it doesn't make sense? And we find that it is actually quite realistic for a rate of formation of glycine or similar biomolecules."

More information: Sasan Esmaili et al. Glycine formation in CO2:CH4:NH3 ices induced by 0-70 eV electrons, The Journal of Chemical Physics (2018). DOI: 10.1063/1.5021596

Journal information: Journal of Chemical Physics

Provided by American Institute of Physics