Light forces electrons to follow the curve

An exotic phenomenon usually associated with high magnetic fields can be achieved without a magnetic field, according to theoretical predictions by researchers from A*STAR and the United States. Their analysis could open the path to a novel type of optoelectronic device operating at long wavelengths.

A charged particle in an electric field experiences a force that drives it along the direction of the field, creating a current. The moving particle can also experience a force perpendicular to its motion. This can happen in the presence of a magnetic field for example, and can lead to a range of unusual properties, particularly when the perpendicular component dominates and the electron starts to follow a skewed trajectory. But this so-called Hall regime often requires large magnetic fields which are impractical for real devices.

Justin Song from the A*STAR Institute of High Performance Computing, working with his colleague Mikhail Kats from the University of Wisconsin-Madison, have theoretically predicted that an unusual Hall-type motion can be harnessed at room temperature and without a magnetic field in a new class of materials known as gapped Dirac materials1. "Dirac materials are semi-metals because of their material symmetries," explains Song. "Narrow-gapped Dirac materials gently break these symmetries, opening up small bandgaps."

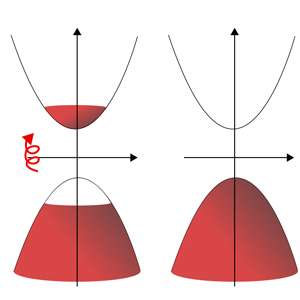

The alternative route to a Hall effect investigated by Song and Kats is based on so-called 'valleys' in these gapped Dirac materials. A valley, in the context of the electronic band structure of a material, is a minimum into which electrons can settle. If there are two valleys with identical energy, the electrons in each of the valleys of gapped Dirac materials feature contrasting trajectories.

Song and Kats exploited this contrast by inducing an imbalance of electrons in one valley over the other via circularly polarized light illumination. They revealed a photo-induced Hall effect (Hall photoconductivity) with strength determined heavily by the wavelength of the light, increasing by a factor of up to one million when switching from visible light to the far infrared.

This means that gapped Dirac materials with a smaller electronic bandgap, such as graphene–boron-nitride heterostructures, are more effective than those with a larger bandgap including molybdenum disulfide.

This phenomenon could be useful for the development of novel far infrared and terahertz optoelectronics. "A particularly tantalizing prospect is a new type of photodetector concept that measures the Hall current in these gapped Dirac materials," says Song. "Such a photodetector could potentially possess zero net dark current even with a large bias voltage."

More information: Justin C. W. Song et al. Giant Hall Photoconductivity in Narrow-Gapped Dirac Materials, Nano Letters (2016). DOI: 10.1021/acs.nanolett.6b02559

Journal information: Nano Letters