Scientists more accurately model the formation and growth of tiny particles that influence clouds and climate

Tiny atmospheric aerosols are some of the most highly studied particles connected with Planet Earth, yet questions remain on how they are formed and how they affect climate. Now Pacific Northwest National Laboratory scientists have developed new approaches to accurately model the birth and growth of these important aerosols.

"Most atmospheric climate models either neglect or estimate how new particles are formed and evolve, rather than using real-world data," said Dr. Jerome Fast, the PNNL atmospheric scientist who led the study. "We used data from observations to create and test three new approaches to model particle formation."

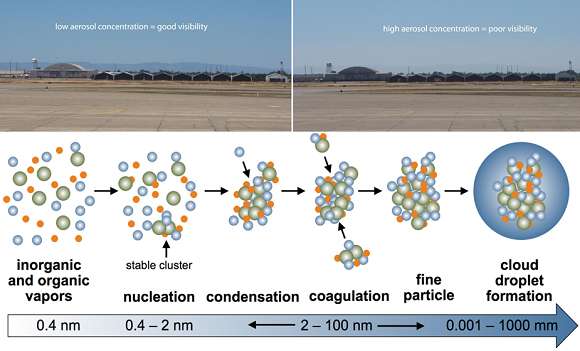

Aerosols are tiny particles that pack a powerful one-two punch. They are scrutinized for their potential climate impact and role in chemical changes happening in the atmosphere. They absorb and scatter the sun's energy, act as the seed around which water vapor condenses to form droplets, and can prompt an overall cooling effect on the atmosphere. Accurately representing the lifecycle of aerosols in climate models requires a strong approach. Like a boxer, their stats matter—concentration, size, and mass (weight) determine their impact.

Real-world measurements help scientists understand how these particles form and grow as well as their characteristics. Those measurements can help improve climate models and provide better answers as to how aerosols influence climate.

The scientists used the Weather and Research Forecasting model with chemistry (WRF-Chem) to simulate new particle formation and growth using data from the 2010 Carbonaceous Aerosol and Radiative Effects Study (CARES) near Sacramento, California. That field campaign looked at the evolution of aerosols, particularly black carbon, from both urban/human-made (pollution emissions) and natural sources (emissions from plants and the sea). During that study, scientists discovered that when the conditions are right, bursts of ultrafine particles form when gas molecules cluster together. These small particles then grow by condensation and coagulation to larger sizes, ultimately changing how cloud droplets form and how solar energy moves through the atmosphere.

In the current study, scientists modified the climate model to expand the size for aerosols it simulated so that even ultrafine (1 nanometer) and larger (10,000 nanometers) aerosols could be included. The team then quantified the approaches to modeling the formation of new particles using surface and airborne measurements of particle number concentration, size distribution, and cloud condensation nuclei made during the CARES field campaign. Further, the team examined differences in rates of condensation, coagulation, transport (how far they travel), deposition (how they collect or deposit on surfaces), and emissions among the three approaches.

"The modeling approaches generally matched our data showing how the concentrations of ultrafine particles changed with time," said Fast. "However, they overestimated the concentrations of particles with diameters greater than 10 nanometers."

Scientists also discovered that new particles were formed over regional scales and were not necessarily local phenomena as previously thought. In one instance, emissions of sulfur dioxide from a large refinery located along San Francisco Bay contributed to bursts of ultrafine particles that subsequently grew as they were transported through the atmospheric to Sacramento.

Because aerosol size distribution remains difficult to pin down in models, scientists will continue studying a wide range of meteorological conditions and aerosol particle sources to improve how climate models simulate the number of particles and how fast they grow.

"The results of our study are promising," said Fast, "but we still have more to do in this area to truly understand how aerosols are born."

More information: A. Lupascu et al. Modeling particle nucleation and growth over northern California during the 2010 CARES campaign, Atmospheric Chemistry and Physics (2015). DOI: 10.5194/acp-15-12283-2015

Journal information: Atmospheric Chemistry and Physics

Provided by Pacific Northwest National Laboratory