July 21, 2011 feature

Shape-changing liquid metal antenna could lead to responsive electronic devices

(PhysOrg.com) -- Researchers have fabricated a fluidic antenna that can change its shape, and therefore the frequency at which it resonates, in response to pressure in a controlled and predictable manner. Shape-changing antennas like this one could be used as sensors, as well as offer new routes of fabricating stimuli-responsive electronics that change their function on demand.

North Carolina State University researchers Mohammad Rashed Khan, Gerard J. Hayes, Ju-Hee So, and Michael D. Dickey, along with Gianluca Lazzi from the University of Utah, have published their study on the liquid metal antenna in a recent issue of Applied Physics Letters.

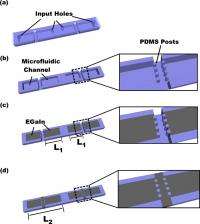

To fabricate the antenna, the researchers injected a conductive, low-viscosity metal alloy (eutectic gallium indium, or EGaIn) into a 51-mm-long microchannel that is divided into four segments. Two rows of posts placed perpendicular to the channel divide the inner and outer segments of the antenna. A thin, membrane-like solid oxide skin spontaneously forms on the metal surface that mechanically stabilizes the metal at the posts, preventing metal in adjacent segments from merging. The liquid metal remains stable as long as its surface oxide is not ruptured.

At a length of 25 mm, the initial dipole antenna state, defined by the two inner segments, represents the shortest of three possible states. As the shortest antenna, it also has the highest frequency. In order to elongate the antenna, and thus decrease its frequency, the researchers applied a critical pressure on the liquid metal at one segment boundary. This critical pressure ruptures the oxide skin and squirts the metal between the posts to merge with one of the outermost metal segments. This process increases the length of the antenna and creates a second state at a lower frequency than the first state. By controlling the spacing between the posts, the researchers could control the pressure at which the oxide ruptures.

To achieve the third state – the one with the longest length and lowest frequency – the researchers ruptured the skin on the other side of the antenna, allowing the liquid metal in the inner segment to merge with the other outer segment. Once the skin is ruptured, the metal flows extremely quickly – in a few milliseconds – due to its low viscosity and the short distance it has to travel.

This antenna is not the first that can be reconfigured to change its frequency or other behavior, but its simple design does offer some advantages. Many reconfigurable antennas involve external mechanical or electrical switches, whereas the current antenna doesn’t require any external switch. In addition, the response of this antenna to stimuli as well as function of the antenna can be controlled and predicted. Also, because it’s encased in an elastic encasing material, the liquid metal antenna can be bent, twisted, and stretched.

The reconfigurable antenna could have applications in a variety of areas, such as wireless sensing or monitoring radio systems, switches, RFID tags, health monitoring, and military applications. Since the frequency change in the liquid metal antenna is currently irreversible, it could also serve as a passive memory element.

“If you are using the antenna as a sensor, then knowing it switches from one frequency to another tells the user something has happened (in our simple example, it suggests the antenna has been exposed to some pressure),” Dickey told PhysOrg.com. “A practical example of this may be an RFID tag. Imagine if you order something from Amazon and the UPS driver scans it when it arrives at your house. If the package has been dropped with sufficient force, then the RFID tag will show a different spectral response than if it has not been dropped. Thus, the RFID tag becomes a sensor.”

In the future, the researchers plan to make improvements to the antenna. For instance, as an alternative to using pressure to alter the antenna’s length, the researchers predict that other types of stimuli, such as flexing the antenna, could also cause the liquid metal to merge into the outer segments. By enabling the antenna to respond to different stimuli responses, they hope to make the switching reversible (so it can go from a high frequency to a low frequency and back again).

“Another reason you might want to change frequencies is to ‘move’ to a part of the spectrum that has a clearer signal (e.g., less interference),” Dickey said. “Truthfully, I don't think our design (in its current state) is practical for this because we can only switch in one direction. Hopefully our next paper will show we can switch both ways.”

More information: Mohammad Rashed Khan, et al. “A frequency shifting liquid metal antenna with pressure responsiveness.” Applied Physics Letters 99, 013501 (2011). DOI: 10.1063/1.3603961

Copyright 2011 PhysOrg.com.

All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten or redistributed in whole or part without the express written permission of PhysOrg.com.