The new atomic age: Building smaller, greener electronics

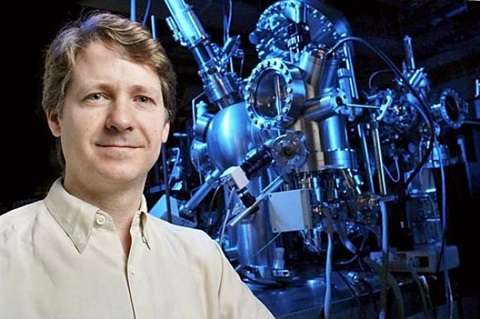

In the drive to get small, Robert Wolkow and his lab at the University of Alberta are taking giant steps forward.

The digital age has resulted in a succession of smaller, cleaner and less power-hungry technologies since the days the personal computer fit atop a desk, replacing mainframe models that once filled entire rooms. Desktop PCs have since given way to smaller and smaller laptops, smartphones and devices that most of us carry around in our pockets.

But as Wolkow points out, this technological shrinkage can only go so far when using traditional transistor-based integrated circuits. That's why he and his research team are aiming to build entirely new technologies at the atomic scale.

"Our ultimate goal is to make ultra-low-power electronics because that's what is most demanded by the world right now," said Wolkow, the iCORE Chair in Nanoscale Information and Communications Technology in the Faculty of Science. "We are approaching some fundamental limits that will stop the 30-year-long drive to make things faster, cheaper, better and smaller; this will come to an end soon.

"An entirely new method of computing will be necessary."

Atomic-scale electronics

Wolkow and his team in the U of A's physics department and the National Institute for Nanotechnology are working to engineer atomically precise technologies that have practical, real-world applications. His lab already made its way into the Guinness Book of World Records for inventing the world's sharpest object—a microscope tip just one atom wide at its end.

They made an earlier breakthrough in 2009 when they created the smallest-ever quantum dots—a single atom of silicon measuring less than one nanometre wide—using a technique that will be awarded a U.S. patent later this month.

Quantum dots, Wolkow says, are vessels that confine electrons, much like pockets on a pool table. The dots can be spaced so that electrons can be in two pockets at the same time, allowing them to interact and share electrons—a level of control that makes them ideally suited for computer-like circuitry.

"It could be as important as the transistor," says Wolkow. "It lays the groundwork for a whole new basis of electronics, and in particular, ultra-low-power electronics."

New discoveries pave way for superior nanoelectronics

Wolkow and his team have built upon their earlier successes, modifying scanning tunnelling microscopes with their atom-wide microscope tip, which emits ions instead of light at superior resolution. Like the needle of a record player, the microscopes can trace out the topography of silicon atoms, sensing surface features on the atomic scale.

In a new paper published in Physical Review Letters, post-doctoral fellow Bruno Martins together with Wolkow and other members of the team, observed for the first time how an electrical current flows across the skin of a silicon crystal and also measured electrical resistance as the current moved over a single atomic step.

Wolkow says silicon crystals are mostly smooth except for these atomic staircases—slight imperfections with each step being one atom high. Knowing what causes electrical resistance and being able to record the magnitude of resistance paves the way to design superior nanoelectronic devices, he says.

In another first, this time led by PhD student Marco Taucer, the research team observed how single electrons jump in and out of the quantum dots, and devised a method of monitoring how many electrons fit in the pocket and measuring the dot's charge. In the past, such observations were impossible because the very act of trying to measure something so extraordinarily small changes it, Wolkow says.

"Imagine that if you looked at something with your eyes, the act of looking at it bent it somehow," he says. "We now can avoid that perturbation due to looking, and so can access and usefully deploy the dots in circuitry."

The team's findings, also published in Physical Review Letters, give scientists the ability to monitor the charge of quantum dots. They've also found a way to create quantum dots that function at room temperature, meaning costly cryogenics is not necessary.

"That's exciting because, suddenly, things that were thought of as exotic, far-off ideas are near. We think we can build them."

Discover the latest in science, tech, and space with over 100,000 subscribers who rely on Phys.org for daily insights. Sign up for our free newsletter and get updates on breakthroughs, innovations, and research that matter—daily or weekly.

Taking the next generation of electronics to the market

Wolkow and his team believe so strongly in the commercial potential of atomic-scale circuitry, two years ago they launched their own spinoff company, Quantum Silicon Inc. Over the next five to six years, QSI plans to demonstrate the potential of these "extremely green" circuits that can make use of smaller, longer-lasting batteries.

It also moves them from the realm of basic to applied research and real-world scenarios, Wolkow says.

"We have this nice connection where we have a training ground for students and highly academic ambitions for progress, but those things quite naturally and immediately transfer to this practical entity."

Much of their efforts initially will focus on creating hybrid technologies—adding atom-scale circuitry to conventional electronics such as GPS devices or satellites, like replacing one link in a chain given the time-intensiveness of making the new circuits. It could take a decade before it's possible to mass-produce atom-scale circuitry, but the future potential is very strong, Wolkow says.

"It has the potential to totally change the world's electronic basis. It's a trillion-dollar prospect."

Journal information: Physical Review Letters

Provided by University of Alberta