Building a neutrino detector with scraps and ingenuity

There's a graveyard behind Duke University's free electron laser lab where physics experiments go to die.

Scraps of metal and cinderblocks litter the ground, which is overgrown by vines and patrolled by the occasional feral cat. Half a dozen stacked shipping containers line the space, filled with accelerator and detector equipment whose time has passed or was never realized.

But it's not all junk. A team of physicists is resurrecting something precious out there: several tons of surplus battleship steel.

The steel is just one component of an ambitious project that's unfolding at Duke and Oak Ridge National Laboratory in Tennessee—a project asking big physics questions on a small budget.

"For now, we're using what we can, all the free resources around us," said Phillip Barbeau, assistant physics professor and collaborator on the project with physics professor Kate Scholberg. So far, he said they've been able to carry out an important preliminary leg of the experiment—that would otherwise cost $500,000—for less than $3,000.

The goal of the work is to probe a powerful source of neutrinos, infinitesimal and chargeless elemental particles that stream through our universe and only rarely interact with other matter. Studying these phantom particles could provide a glimpse into the chemistry of dying stars, explain some mysteries of the atomic nucleus, and just possibly lead to the discovery of new physics beyond the standard model that describes our world.

One kind of neutrino interaction in particular could answer all of these questions—but observing it is an aspiration many have shared, yet none, so far, have accomplished. The team wants to measure a neutrino smacking into the entire nucleus of an atom, not just some of its constituent protons or neutrons.

"In 40 years, no one has managed to succeed," said Barbeau. But a combination of good timing, mature technologies and scrappy work ethic makes the team optimistic that they could be the first.

Before any of that happens, however, they've got to move some steel.

In 1992, the Duke free electron laser laboratory bought 100 tons of military surplus steel from Norfolk Navy Yard. The metal was simply labeled ship steel, but as laboratory project coordinator Joe Faircloth said, "Who would put heat-treated steel on a regular ship?"

So, the story goes, it's likely battleship steel. The 100 tons have been whittled down in the decades since they arrived and given new life around the laboratory. But stacks of the metal sheets still rest out back, a little corroded by the elements. Now, instead of deflecting gunfire or torpedoes, the steel will shield against rogue subatomic particles.

Metals forged before World War II have lower radioactivity because nuclear bomb testing induced a small but measurable increase in the earth's surface radiation. This makes pre-WWII steel very useful for physicists trying to block particles and electromagnetic waves from reaching sensitive detectors like the ones Philip Barbeau builds.

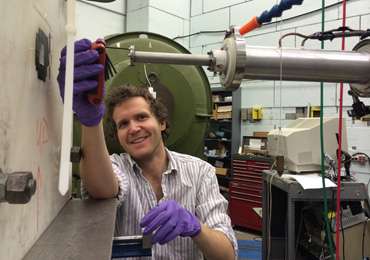

Barbeau is an authority on particle detectors, which do just what their name implies—snag subatomic particles as they whiz by and transmit their signals into interpretable data. Some particles are trickier than others to detect. Neutrinos, in particular, give off a small, sensitive signal that's easily swamped by background noise. So the team is building what looks like a crypt made of concrete and the low-radiation battleship steel to encase their detectors. The crypt and many other layers of shielding will allow neutrinos to fly through, but radiation and other particles will be blocked.

Powerful shielding is going to be particularly important where they plan to run the experiment, near the Spallation Neutron Source (SNS) at Oak Ridge National Laboratory.

Kate Scholberg is a professor of physics and Bass fellow who studies neutrinos.

"SNS's goal in life is to create neutrons," said Kate Scholberg. Neutrons are the chargeless particles that, together with protons, make up the nuclei of elements. They produce the kind of background noise that would overwhelm the team's detectors, making SNS seem like a counterintuitive location for their experiment.

But as a by-product of its neutron generation, SNS also produces neutrinos—lots of them. A few dozen meters away from the SNS, scientists can detect as many neutrinos in one day as they'd see from a supernova at the center of the Milky Way.

"It's an absolutely gorgeous neutrino source," said Scholberg. "At this time, it's the brightest neutrino source of its type, and it has a really nice time-structure."

"The neutrinos come for free, but the drawback, the catch, is that it's also a neutron source," Scholberg said. "And they're sneaky little things, flying around, trying to sneak into cracks."

"We're trying to use the facility in a different way than it was originally intended," said Grayson Rich, a physics graduate student at UNC-Chapel Hill who works with Barbeau and Scholberg on the project.

Barbeau is leaving no detector untested in the build up to the experiment. He and Rich have been calibrating dozens of detector types at the Triangle Universities Nuclear Laboratory (TUNL), yet another free resource available to them. At TUNL, they can simulate interactions that might happen when they deploy the full-sized detectors at SNS, thereby working out kinks and glitches in advance.

The detectors are loaded with chemical elements or compounds—sodium iodide, cesium idodide, helium, xenon and argon to name a few—whose atoms will hopefully interact with the neutrinos streaming from the SNS.

The more detectors they employ, the better their chances to see what no one has before.

"Now it really seems like the time is right," Scholberg said.

There are multiple names for the neutrino phenomenon they're looking for, but Scholberg likes to call it coherent elastic neutrino-nucleus scattering, or CENNS. It has eluded scientists since it was first predicted 40 years ago, primarily for lack of advanced detectors.

The gist of CENNS is this: neutrinos of a certain energy level should be able to interact with the whole nucleus of an atom, rather than its constituent particles. Barbeau and Scholberg liken the scenario to a cue ball (neutrino) hitting a bowling ball (atomic nucleus). The cue ball will only move the bowling ball a tiny amount—but for very sophisticated detectors, that measurement alone should be enough to tell where a neutrino has been.

"We're just looking at the kinetic energy of recoil when the cue ball hits the bowling ball," Barbeau said.

"The SNS is the perfect neutrino source for this measurement, because it's high enough energy to kick the nuclei so you can see it, but not so high that it's not coherent anymore," Scholberg said.

CENNS is believed to play a role in the heart of supernovae. When a massive star's core collapses, it releases a flux of neutrinos. Scientists predict those particles smack into much larger nuclei and collectively help to expel the core's material outward. Observing CENNS could confirm this.

The team is also interested in CENNS as a clean, simple way to test the standard model of physics. They expect to observe the phenomenon as it's been predicted, but if they don't—if they measure something strange—that could be a sign of new physics.

"It's an opportunity to make some unprecedented tests of the standard model," Scholberg said.

The project is still in its early stages right now. After extensive testing at SNS and TUNL, Barbeau and Rich plan to rent a moving truck and haul their steel and detectors up to Tennessee. There, they'll build their experiment and wait for the neutrinos to start streaming in. If all goes well, they'll submit an official proposal and shoot for a much larger budget.

It could be a couple years before they obtain meaningful data, but the team is patient. After all, the steel, the predictions and the technology have been decades in the making. Unprecedented tests—with an unprecedented price tag—are worth the wait.

Provided by Duke University