Quantum process increases the number of electrons produced when light strikes a metal-dielectric interface

Researchers at MIT and elsewhere have found a way to significantly boost the energy that can be harnessed from sunlight, a finding that could lead to better solar cells or light detectors.

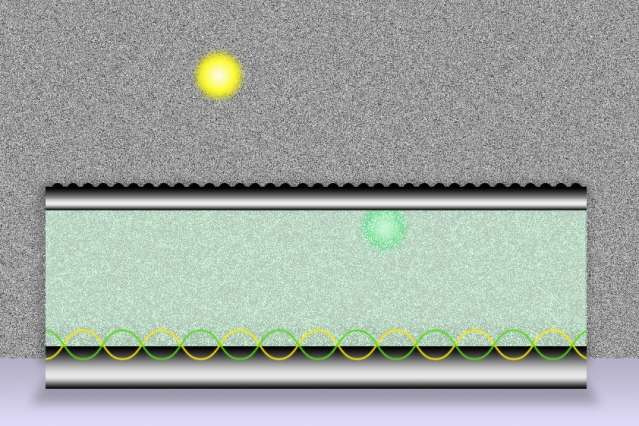

The new approach is based on the discovery that unexpected quantum effects increase the number of charge carriers, known as electrons and "holes," that are knocked loose when photons of light of different wavelengths strikes a metal surface coated with a special class of oxide materials known as high-index dielectrics. The photons generate what are known as surface plasmons—a cloud of oscillating electrons that has the same frequency as the absorbed photons

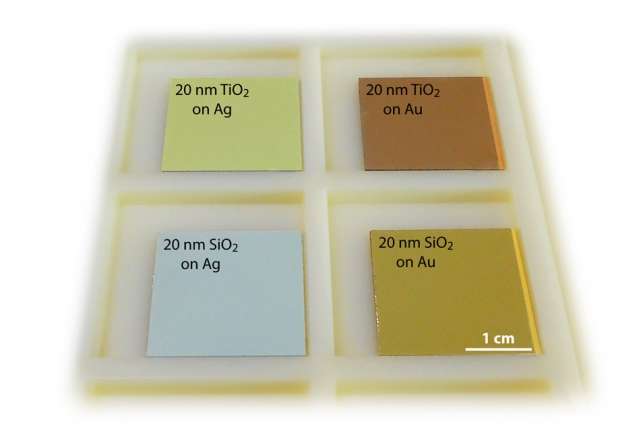

The surprising finding is reported this week in the journal Physical Review Letters by authors including MIT's Nicholas Fang, an associate professor of mechanical engineering, and postdoc Dafei Jin. The researchers used a sheet of silver coated with an oxide, which converts light energy into polarization of atoms at the interface.

"Our study reveals a surprising fact: Absorption of visible light is directly controlled by how deeply the electrons spill over the interface between the metal and the dielectric," Fang says. The strength of the effect, he adds, depends directly on the dielectric constant of the material—a measure of how well it blocks the passage of electrical current and converts that energy into polarization.

"In earlier studies," Fang says, "this was something that was overlooked."

Previous experiments showing elevated production of electrons in such materials had been chalked up to defects in the materials. But Fang says those explanations "were not enough to explain why we observed such broadband absorption over such a thin layer" of material. But, he says, the team's experiments back the newfound quantum-based effects as an explanation for the strong interaction.

The team found that by varying the composition and thickness of the layer of dielectric materials (such as aluminum oxide, hafnium oxide, and titanium oxide) deposited on the metal surface, they could control how much energy was passed from incoming photons into generating pairs of electrons and holes in the metal—a measure of the system's efficiency in capturing light's energy. In addition, the system allowed a wide range of wavelengths, or colors, of light to be absorbed, they say.

The phenomenon should be relatively easy to harness for useful devices, Fang says, because the materials involved are already widely used at industrial scale. "The oxide materials are exactly the kind people use for making better transistors," he says; these might now be harnessed to produce better solar cells and superfast photodetectors.

"The addition of a dielectric layer is surprisingly effective" at improving the efficiency of light harnessing, Fang says. And because solar cells based on this principle would be very thin, he adds, they would use less material than conventional silicon cells.

Because of their broadband responsiveness, Fang says, such systems also respond much faster to incoming light: "We could receive or detect signals as a shorter pulse" than current photodetectors can pick up, he explains. This could even lead to new "li-fi" systems, he suggests—using light to send and receive high-speed data.

N. Asger Mortensen, a professor at Danish Technical University who was not involved in this work, says this finding "has profound implications for our understanding of quantum plasmonics. The MIT work really pinpoints … how plasmons are subject to an enhanced decay into electron-hole pairs near the surface of a metal."

"Probing these quantum effects is very challenging both theoretically and experimentally, and this discovery of enhanced absorption based on quantum corrections represents an important leap forward," adds Maiken Mikkelsen, an assistant professor of physics at

Duke University who also was not involved in this work. "I think there is no doubt that harnessing the quantum properties of nanomaterials is bound to create future technological breakthroughs."

More information: Dafei Jin et al. Quantum-Spillover-Enhanced Surface-Plasmonic Absorption at the Interface of Silver and High-Index Dielectrics, Physical Review Letters (2015). DOI: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.115.193901

Journal information: Physical Review Letters

Provided by Massachusetts Institute of Technology

This story is republished courtesy of MIT News (web.mit.edu/newsoffice/), a popular site that covers news about MIT research, innovation and teaching.