Blood flow lends insights to bird flight and motion

The blood flow to leg bones in birds has been shown to correlate to their locomotion patterns.

Researchers at the Universities of Western Australia and Adelaide compared volant (flying) and cursorial (running) birds by estimating blood flow from the size of the nutrient foramen (hole) in the femur. The artery supplying the bone passes through this hole.

They looked at 100 species of living birds and measured the area of the foramen opening, which represented the size of the blood vessel passing through it, and also measured volume and mass of the femur.

When the effect of body size was taken into account, the researchers found the blood flow index of the nutrient foramen was about two times larger in birds that move primarily by running than in birds that mainly fly.

UWA's Shane Maloney says this made sense, given the role blood flow plays in remodelling mammalian bones, but it had never been demonstrated before in birds.

"Intriguingly, estimated blood flow rate to the femur of birds was about twice that of mammals, possibly because birds use only two legs during locomotion, while mammals usually use four," Professor Maloney says.

"We knew cursorial species put much greater stresses on their legs than volant species and an important driver of blood flow is the repair of damage caused by those stresses.

"In cursorial species we predicted more damage, which would require higher blood flow, leading to larger foramen, and that's what we found."

Blood flow measure used to classify extinct birds

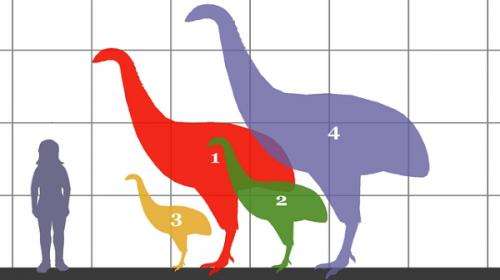

A fellow author also measured foramen size in well-preserved fossil bones of moa (extinct giant birds of New Zealand).

"Because we can't go out and measure the physiology of extinct birds we need to find ways to assess how they functioned," Prof Maloney says.

"One way is to use differences in living birds to make predictions about the way characteristics vary between different classifications, such as flying versus running, and also between cold-blooded reptiles and warm-blooded animals.

"When we find certain characteristics predict which classification a mammal or bird or reptile belongs to, we can use those characteristics in extinct animals to conclude what classification they fit into."

Professor Maloney says an interesting finding was the possible differences in foramen size between sexes in birds.

"One hypothesis is the necessity for female birds to mobilise calcium from bone for egg shell formation, a requirement that doesn't exist in males," he says.

"If this prediction turns out to be true, then we may have discovered a way to sex the fossils of egg-laying animals."

More information: Blood flow for bone remodelling correlates with locomotion in living and extinct birds. Allan GH, et al. J Exp Biol. 2014 Jun 4. pii: jeb.102889. [Epub ahead of print] www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24902751

Provided by Science Network WA