Pollutant-eating bacteria not so rare

(Phys.org) —Dioxane, a chemical in wide industrial use, has an enemy in naturally occurring bacteria that remove it from the environment. Researchers at Rice University have found that these bacteria are more abundant at spill sites than once thought.

They are designing tools to help environmental engineers determine the best way to clean up a contaminated site.

A Rice-led team discovered soluble di-iron mono-oxygenase (SDIMO) genes in bacteria thriving in contaminated Alaskan groundwater. The genes produce enzymes that degrade dioxane – specifically, the common form known as 1,4-Dioxane – into harmless substances.

The work may lead to the creation of biomarker-based forensic tools to detect SDIMO-carrying bacteria at dioxane-polluted sites, according to Pedro Alvarez, the George R. Brown Professor and chair of Rice's Civil and Environmental Engineering Department.

A study by Alvarez and colleagues, including lead author and Rice graduate student Mengyan Li, appears this month in the American Chemical Society journal Environmental Science and Technology.

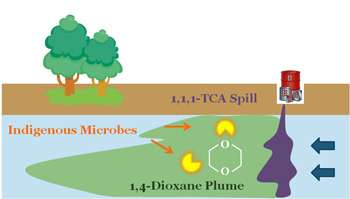

Dioxane can get into the ground in accidental spills of 1,1,1-trichloroethane (TCA). Dioxane is used to stabilize TCA, an industrial solvent, and often serves as a solvent itself.

"This contaminant has been flying under the radar," said Alvarez, who also serves on the Environmental Protection Agency's science advisory board. "It is a suspected carcinogen, but for a contaminant to be important or of emerging concern, it has to pose a threat to a large number of people or impact large areas."

He said it was once assumed dioxane would not biodegrade, but the recent discovery of dioxane-eating bacteria prompted a new look. "The common wisdom has been that these bacteria are very rare," Alvarez said. "So people focused on physical and chemical treatment processes that are expensive and marginally effective, especially to treat very large, dilute plumes."

One such plume exists on Alaska's oil-producing North Slope. With the support of BP America, the researchers studied samples from various points and depths in the plume to look for SDIMO genes. Li decoded genes from bacteria in the samples and found SDIMO-carrying bacteria to be most prevalent near the spill source, less so toward the edges.

In tests on the samples, Li also found that the bacteria stopped degrading dioxane after about 15 days, but adding sodium acetate rebooted the process of turning the pollutant into harmless water and carbon dioxide.

If dioxane-eating bacteria can thrive in the harsh Alaskan environment, they're likely to be found in great abundance in more tropical climates, Alvarez said. The researchers are testing their theory at four such sites.

"This genetic biomarker lets us know with a great degree of certainty that these microbes are present," he said. "If you have more workers, the job gets done faster."

Determining the concentration of SDIMO-carrying bacteria will allow environmental engineers to ascertain when a process called monitored natural attenuation (MNA) is sufficient to clean up a large plume, or whether more aggressive remediation efforts are necessary, he said.

"When you propose MNA, the burden of proof is on the proponent," Alvarez said. "You have to demonstrate the bacteria out there can do the job and they are degrading contaminants faster than they're migrating. There is a correlation between the concentration of these biomarkers and how many capable degraders are present, and that tells you about the potential rate of degradation."

He said researchers now want to know how the degraders gather. "Is it because biodegradation capabilities spread out through the selective pressure that more contamination exerts on bacteria?" Alvarez asked. "Are they evolving? Is this due to horizontal gene transfer among bacteria?

"Or are we just getting better at finding them with new analytical tools? I don't have the answer, but that's one of the things we hope to look into," he said.

More information: pubs.acs.org/doi/abs/10.1021/es402228x

Journal information: Environmental Science and Technology

Provided by Rice University