This article has been reviewed according to Science X's editorial process and policies. Editors have highlighted the following attributes while ensuring the content's credibility:

fact-checked

trusted source

proofread

Singlish goes digital: How Singaporeans infuse their distinctive language into online communication

"30th got school meh it's a Sunday leh." If we asked an average American what this online message means and what they can discern about its author, they would likely be baffled.

But if we asked a local here in Singapore, or someone who has been living here for a while, they would easily identify this as Singlish, and explain that the person communicating is expressing skepticism that there would be school on the 30th because that day is a Sunday.

They might make an informed guess that the author is Singaporean, and that they are expressing themselves very casually to someone they are close to, maybe a friend. As for the gender of the author, they might hazard a guess that the writer is more likely to be male, based on the forceful tone conveyed by the message's wording.

Despite the access we have today to global media and the internet, researchers in linguistics (the study of language) have observed that our language use in "digital" contexts, like social media and SMS communication, remains highly regional, and is quite similar to how we speak in face-to-face-interactions.

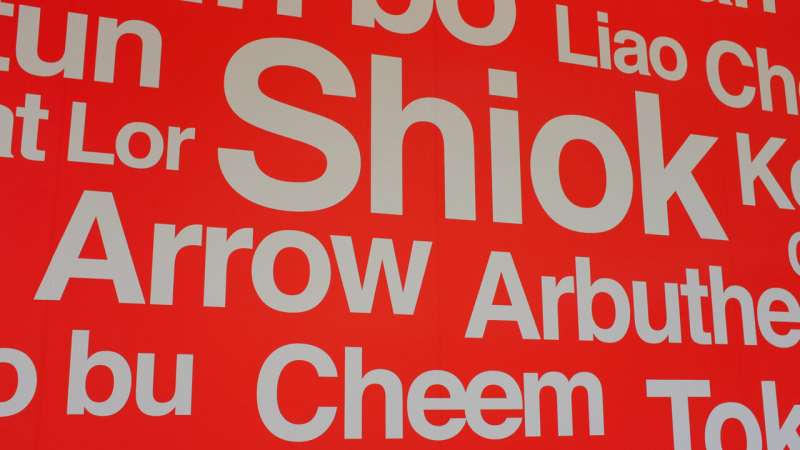

In the context of Singapore, this means that Singlish (or, as many linguists call it, "Colloquial Singapore English"), our local English that has been shaped over time by varieties of Chinese, Malay, and other local languages, is used by many individuals not only in spoken communication, but also in online written communication.

The rise of digital communication presents exciting opportunities for linguists, and particularly for sociolinguists, who study how language functions in society. For many decades, sociolinguists at NUS have investigated topics related to how language is used in Singapore, including how Singaporeans with different social backgrounds speak and write in various situations.

One of the most significant achievements of linguistics research in Singapore to date is the development of a collection of real texts and conversations in Singapore English within the larger International Corpus of English (ICE), a set of linguistic databases that collects examples of English from around the world.

This corpus has helped linguists identify some of the many impacts of other languages on Singlish—for example, NUS Professor Bao Zhiming has used the corpus to examine how the Chinese language has influenced the structure of Singlish sentences that describe conditions and outcomes, such as, "You eat already you can die one."

But the ICE-Singapore corpus was developed more than 20 years ago—so, while it is a valuable source of data for how Singapore English was used historically, there is a need to collect newer data to understand how Singaporeans use English today.

My colleague Associate Professor Mie Hiramoto had this need for updated data on Singapore English in mind in 2016 when she developed a concept for a new corpus. "The idea for the project began as an exercise for my undergraduate module on language contact," she explained.

"I wanted students to work with some simple language data that they had easy access to—so, I thought of asking them to use their existing chat logs from WhatsApp."

"From a practical perspective, the study of language patterns connects with a number of industry sectors—automatic speech recognition, machine translation, forensic linguistics, speech therapy, and language teaching, among others.

"In terms of scientific inquiry, the structure of language varieties like Singlish, which arise from contact between multiple languages, can tell us crucial things about how the brain processes information."

After seeing the wealth of data students were able to collect, Hiramoto realized that this corpus had significant potential beyond the scope of a class exercise. With this in mind, she obtained ethics approval to compile the data for research purposes upon receiving consent from the chat participants.

Each year, students in the course were invited to contribute their anonymized WhatsApp messages. Ultimately, Assoc Prof Hiramoto said, "it grew into the corpus we have today, of nearly 10.6 million words."

Working with an international team of linguistics researchers, including Professor Jakob Leimgruber at the University of Regensburg, Dr. Wilkinson Gonzales at the Chinese University of Hong Kong, Jun Jie Lim at the University of California San Diego, and Mohamed Hafiz at NUS, Assoc Prof Hiramoto processed this large corpus of language data, now titled the Corpus of Singapore English Messages (CoSEM), and in 2022 released it publicly for the benefit of other researchers.

The data includes background information about each chat contributor, including their age, gender, ethnicity, and nationality—this sort of information is crucial for sociolinguists, because it allows us to investigate patterns in Singapore English among different social groups.

What kinds of information can we learn from CoSEM? Let's return to the intuitions of the local Singaporean above, who felt that the example message was likely from a male author. In 2020, the CoSEM research team released an article investigating patterns in the use of "sentence-final particles," meaning the famous particles such as lah, leh, and meh that are typical of Singlish.

In their analysis, the authors found that many of these particles, including meh, are indeed used significantly more frequently by men in the corpus. Not only this, but there are also major ethnicity-based differences in who uses which particles—for example, Indian Singaporeans use lah more frequently than other groups, while Chinese Singaporeans are the most frequent users of bah, which is one of the only discourse particles that originates from Mandarin (rather than Hokkien or Cantonese).

Using CoSEM data, Hiramoto and the research team were also able to identify usage patterns of new particles entering Singlish, such as sia—these findings underscore that Singlish is not a static variety, but, like all language varieties, continues to evolve over time.

While these patterns are interesting to read about, some might wonder, why do linguists want to study Singlish in the first place? From a practical perspective, the study of language patterns connects with a number of industry sectors—automatic speech recognition, machine translation, forensic linguistics, speech therapy, and language teaching, among others.

In terms of scientific inquiry, the structure of language varieties like Singlish, which arise from contact between multiple languages, can tell us crucial things about how the brain processes information. And in the study of public policy, investigating how Singlish has changed over time can help us understand the role of local languages as symbols of national identity.

For all of these reasons, and more, linguists including Assoc Prof Hiramoto and myself in the Department of English, Linguistics and Theater Studies are passionate about investigating how people use language—even when sending a simple WhatsApp message.

More information: The Corpus of Singapore English Messages (CoSEM). osf.io/2ghj9/

Provided by National University of Singapore