This article has been reviewed according to Science X's editorial process and policies. Editors have highlighted the following attributes while ensuring the content's credibility:

fact-checked

trusted source

proofread

Take a trip to the largest lake on Mars

Mars once hosted a lake larger than any on Earth. The broken-down and dried-up remnants of this ancient lakebed are shown here in amazing detail by ESA's Mars Express.

This patch of Mars—shown in a new view from Mars Express's High Resolution Stereo Camera (HRSC)—is known as Caralis Chaos. We believe that water, and a lot of it, once existed here.

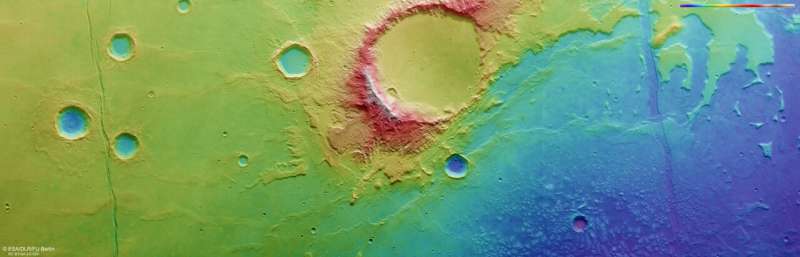

The lower-right part of the frame features the remains of an old lakebed (seen most clearly in the associated topographic view below, where it shows up in tones of blue). The boundaries of this bed can be seen curving up and away from the bottom-center of the frame towards the top right, skirting around the large central crater.

The old lakebed is now filled with lots of raised mounds, thought to have formed as ancient martian winds swept dust across the planet; this dust was later covered and altered by water, before drying out again and breaking apart.

The wider region surrounding Caralis Chaos actually contains a few old lake basins that have worn away over time. Together, these basins form the remnants of a vast ancient lake that covered an area of more than 1 million square kilometers: Lake Eridania.

Lake Eridania once held more water than all other Martian lakes combined and was larger than any known lake on Earth, containing enough water to fill the Caspian Sea nearly three times over. It likely existed around 3.7 billion years ago, first as one large body of water and later as a series of smaller isolated lakes as it began to dry out. Eventually, this once-colossal lake disappeared completely, along with the rest of the water on the planet.

Cracks and craters

Alongside water, there are clear signs of volcanism at play in and around Caralis Chaos.

Two long cracks run vertically down through this image, cross-cutting both the aforementioned lakebed and the smoother ground to the left. These are known as the Sirenum Fossae faults, and formed as Mars's Tharsis region—home to the largest volcanoes in the solar system—rose up and put immense stress on Mars's crust.

Volcanic stress is also to blame for the many wrinkle ridges found here. These appear as wriggly lines weaving across the frame horizontally. Wrinkle ridges are common on volcanic plains, forming as new lava sheets are compressed while still soft and elastic, causing them to buckle and deform.

The impact craters here, created as space rocks collided with Mars, are also fascinating. The large central crater shows signs of flowing material and carved-out valleys on its southern (left) rim, indicating that water may have existed here even after Lake Eridania disappeared.

The smaller crater to its south (left) has been eaten away by small gullies on its northern (right) flank, while the rightmost part of the image displays a number of ancient craters that are barely recognizable as craters, having been heavily broken down and eroded away over time.

Exploring Mars

Mars Express has been orbiting the Red Planet since 2003. It is imaging Mars's surface, mapping its minerals, identifying the composition and circulation of its tenuous atmosphere, probing beneath its crust, and exploring how various phenomena interact in the Martian environment.

The spacecraft's HRSC has revealed much about Mars's diverse surface in the past 20 years. Its images show everything from wind-sculpted ridges and grooves to sinkholes on the flanks of colossal volcanoes to impact craters, tectonic faults, river channels and ancient lava pools. The mission has been immensely productive over its lifetime, creating a far fuller and more accurate understanding of our planetary neighbour than ever before.

Provided by European Space Agency