This article has been reviewed according to Science X's editorial process and policies. Editors have highlighted the following attributes while ensuring the content's credibility:

fact-checked

peer-reviewed publication

trusted source

proofread

100 kilometers of quantum-encrypted transfer

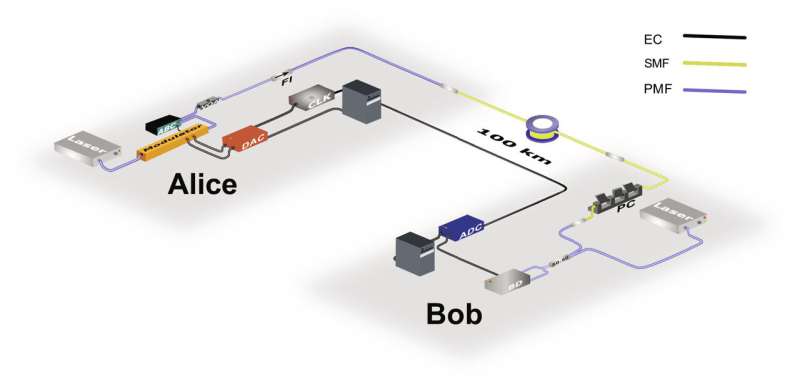

Researchers at DTU have successfully distributed a quantum-secure key using a method called continuous variable quantum key distribution (CV QKD). The researchers have managed to make the method work over a record 100 km distance—the longest distance ever achieved using the CV QKD method. The advantage of the method is that it can be applied to the existing Internet infrastructure.

Quantum computers threaten existing algorithm-based encryptions, which currently secure data transfers against eavesdropping and surveillance. They are not yet powerful enough to break them, but it's a matter of time. If a quantum computer succeeds in figuring out the most secure algorithms, it leaves an open door to all data connected via the internet. This has accelerated the development of a new encryption method based on the principles of quantum physics.

But to succeed, researchers must overcome one of the challenges of quantum mechanics—ensuring consistency over longer distances. Continuous variable quantum key distribution has so far worked best over short distances.

"We have achieved a wide range of improvements, especially regarding the loss of photons along the way. In this experiment, published in Science Advances, we securely distributed a quantum-encrypted key 100 kilometers via fiber optic cable. This is a record distance with this method," says Tobias Gehring, an associate professor at DTU, who, together with a group of researchers at DTU, aims to be able to distribute quantum-encrypted information around the world via the internet.

Secret keys from quantum states of light

When data needs to be sent from A to B, it must be protected. Encryption combines data with a secure key distributed between sender and receiver so both can access the data. A third party must not be able to figure out the key while it is being transmitted; otherwise, the encryption will be compromised. Key exchange is, therefore, essential in encrypting data.

Quantum key distribution (QKD) is an advanced technology that researchers are working on for crucial exchanges. The technology ensures the exchange of cryptographic keys by using light from quantum mechanical particles called photons.

When a sender sends information encoded in photons, the quantum mechanical properties of the photons are exploited to create a unique key for the sender and receiver. Attempts by others to measure or observe photons in a quantum state will instantly change their state. Therefore, it is physically only possible to measure light by disturbing the signal.

"It is impossible to make a copy of a quantum state, as when making a copy of an A4 sheet—if you try, it will be an inferior copy. That's what ensures that it is not possible to copy the key. This can protect critical infrastructure such as health records and the financial sector from being hacked," explains Gehring.

Works via existing infrastructure

The CV QKD technology can be integrated into the existing internet infrastructure.

"The advantage of using this technology is that we can build a system that resembles what optical communication already relies on."

The backbone of the internet is optical communication. It works by sending data via infrared light running through optical fibers. They function as light guides laid in cables, ensuring we can send data worldwide. Data can be sent faster and over longer distances via fiber optic cables, and light signals are less susceptible to interference, which is called noise in technical terms.

"It is a standard technology that has been used for a long time. So, you don't need to invent anything new to be able to use it to distribute quantum keys, and it can make implementation significantly cheaper. And we can operate at room temperature," explains Gehring. "But CV QKD technology works best over shorter distances. Our task is to increase the distance. And the 100 kilometers is a big step in the right direction."

Noise, errors, and assistance from machine learning

The researchers succeeded in increasing the distance by addressing three factors that limit their system in exchanging the quantum-encrypted keys over longer distances:

Machine learning provided earlier measurements of the disturbances affecting the system. Noise, as these disturbances are called, can arise, for example, from electromagnetic radiation, which can distort or destroy the quantum states being transmitted. The earlier detection of the noise made it possible to reduce its corresponding effect more effectively.

Furthermore, the researchers have become better at correcting errors that can occur along the way, which can be caused by noise, interference, or imperfections in the hardware.

"In our upcoming work, we will use the technology to establish a secure communication network between Danish ministries to secure their communication. We will also attempt to generate secret keys between, for example, Copenhagen and Odense to enable companies with branches in both cities to establish quantum-safe communication," Gehring says.

We don't exactly know what happens—yet

QKD was developed as a concept in 1984 by Bennett and Brassard, while the Canadian physicist and computer pioneer Artur Ekert and his colleagues carried out the first practical implementation of QKD in 1992. Their contribution has been crucial for developing modern QKD protocols, a set of rules, procedures, or conventions that determine how a device should perform a task.

QKD is based on a fundamental uncertainty in copying photons in a quantum state. Photons are the quantum mechanical particles that light consists of.

Photons in a quantum state carry a fundamental uncertainty, meaning it is not possible with certainty to know whether the photon is one or several photons collected in the given state, also called coherent photons. This prevents a hacker from measuring the number of photons, making it impossible to make an exact copy of a state.

They also carry a fundamental randomness because photons are in multiple states simultaneously, also called superposition. The superposition of photons collapses into a random state when the measurement occurs. This makes it impossible to measure precisely which phase they are in while in superposition.

Together, it becomes nearly impossible for a hacker to copy a key without introducing errors, and the system will know if a hacker is trying to break in and can shut down immediately. In other words, it becomes impossible for a hacker to first steal the key and then to avoid the door locking as he tries to put the key in the lock.

CV QKD focuses on measuring the smooth properties of quantum states in photons. It can be compared to conveying information in a stream of all the nuances of colors instead of conveying information step by step in each color.

More information: Adnan A. E. Hajomer et al, Long-distance continuous-variable quantum key distribution over 100-km fiber with local local oscillator, Science Advances (2024). DOI: 10.1126/sciadv.adi9474

Journal information: Science Advances

Provided by Technical University of Denmark