This article has been reviewed according to Science X's editorial process and policies. Editors have highlighted the following attributes while ensuring the content's credibility:

fact-checked

trusted source

proofread

A different picture of the Serengeti: Competition for food drives planet's remaining mass migration of herbivores

Upending the prevailing theory of how and why multi-species mass-migration patterns occur in Serengeti National Park, researchers from Wake Forest University have confirmed that the millions-strong wildebeest population pushes zebra herds along in competition for the most nutrient-dense grasses.

The study resulting from this research, "Interplay of competition and facilitation in grazing succession by migrant Serengeti herbivores," appears in Science.

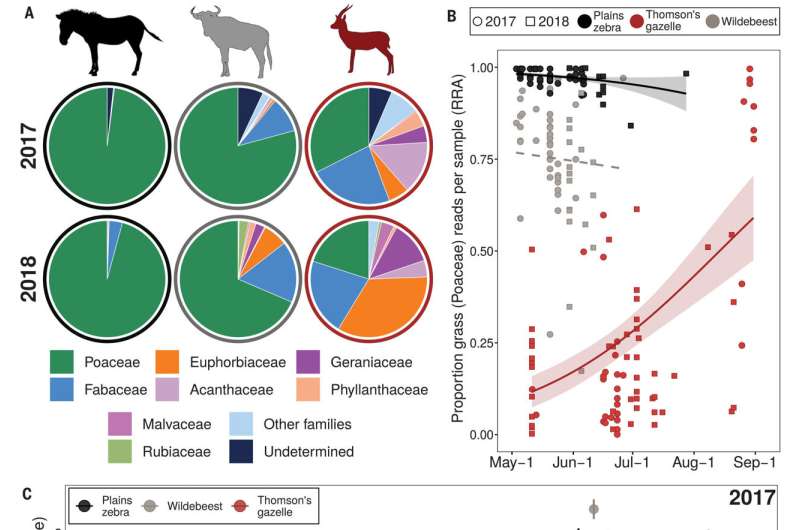

For decades, biologists have believed the major grazing populations in Serengeti—zebra, then wildebeest and then Thomson's gazelle—each cleared the way for the smaller herbivores that followed, facilitating their access to the plants they preferred.

This study paints a different picture of the Serengeti landscape. Based on the largest and most comprehensive data analysis to date, it is the first study to combine information from camera traps, GPS collars on individual animals, diet analysis and satellites that track the effects fires and rainfall have on the grassland.

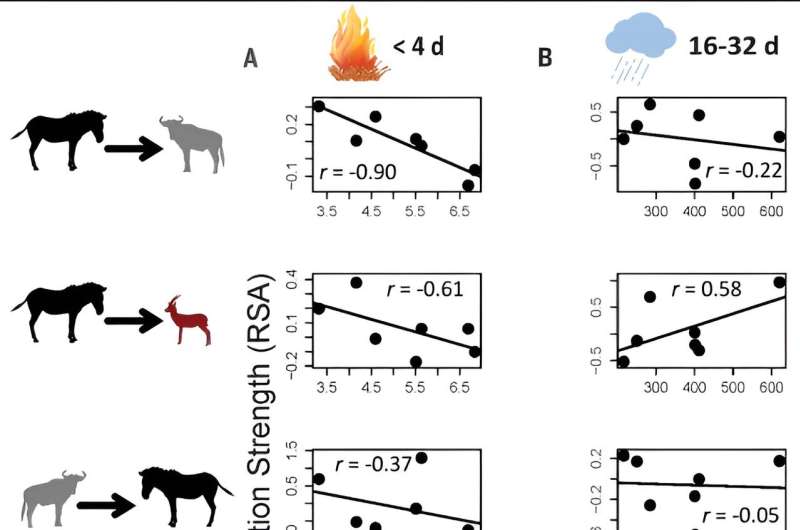

The research team, led by Wake Forest University Professor of Biology T. Michael Anderson, demonstrates that wildebeest and zebra compete for the best parts of the tall grasses that cover Serengeti. Once those two grazing populations move on, the gazelle then can access the flowering plants and shrubs that grow beneath the grass cover.

"Zebra are essentially bulk feeders. They require a large amount of vegetation in order to meet their energy demands," explained Anderson, the study's principal investigator and corresponding author. "If they stayed behind the wildebeest, the wildebeest would just consume all the vegetation and the zebra wouldn't be able to meet those energy demands. That observation was novel, and we call it the push-pull hypothesis for grazing succession. Instead of facilitation, it's competition on the front end."

The zebra population is around 200,000 strong in Serengeti, whereas the wildebeest top 1.3 million.

"It's like an enormous lawn mower," Anderson said. "They have a huge effect on the grass biomass."

Serengeti is the perfect setting for such a study. Because many of the multi-species mass migrations on the planet have been eliminated, the movement of the zebra, wildebeest and gazelle is unique.

Typically, three factors can influence herbivore mass-migration patterns: competition for food; facilitation, or the act of one species improving the foraging opportunities for another; and predation, where the grazing animals form mixed herds to avoid being eaten.

Competition influences the larger of the Serengeti species migration, but facilitation does come into play. While the wildebeest push the zebra in competition for food, the larger species make it easier for the gazelle to reach those rare forbs—flowering plants—that offer them the most nutrition. Later in the season, the gazelle switch to eating the young grasses that are regrowing in the wake of the zebra and wildebeest grazing.

Anderson said the findings in Serengeti have application across the globe, where scientists are trying to restore the vast grasslands where plants and animals co-evolved. As Serengeti still functions the way it did hundreds of thousands of years ago, its management can help inform projects such as American Prairie.

"If we're going to learn to manage these ecosystems in the face of global climate change and increasing anthropogenic effects, we are going to have to learn from these mechanisms," he said.

The research team included Staci Hepler, Robert J. Erhardt and Robert Sketch of the Wake Forest University Department of Statistical Sciences, as well as Jeffrey Muday of the biology department.

Anderson and Hepler, one of the project's statisticians, both said the collaboration between the departments led to much stronger results after the data analysis. Understanding the biology, Hepler said, allowed her to create statistical models for the project.

"The hypotheses around competition, facilitation and predation have been around for a long time, but they are hard to validate with the data that are typically available," she explained. "Our collaboration required lots of conversations with the biologists explaining the processes and theories, and me explaining the modeling we were doing, so the models being developed could actually test the hypotheses. You have to have collaborations to make sure you're answering the right questions."

Also contributing were Ricardo M. Holdo and Jason E. Donaldson of the University of Georgia; J. Grant C. Hopcraft and Thomas A. Morrison of the University of Glasgow; Matthew C. Hutchinson of University of California Merced; Sarah E. Huebner and Craig Packer of University of Minnesota; Issack N. Munuo of Serengeti Wildlife Research Institute; and Meredith S. Palmer, Johan Pansu and Robert M. Pringle of Princeton University.

Anderson and several of the paper's co-authors are using similar data to look at parasite dynamics in Serengeti herbivores in an effort to determine how nematodes, or parasites living the guts of grazers, move around in the landscape. The findings could aid in the understanding of how such parasites are transferred to domestic animals living on the edges of the national park.

More information: T. Michael Anderson et al, Interplay of competition and facilitation in grazing succession by migrant Serengeti herbivores, Science (2024). DOI: 10.1126/science.adg0744. www.science.org/doi/10.1126/science.adg0744

Provided by Wake Forest University