This article has been reviewed according to Science X's editorial process and policies. Editors have highlighted the following attributes while ensuring the content's credibility:

fact-checked

proofread

Study shows pesticide spread in an alpine ecosystem from the valley to the summit region

The Venosta Valley is located in South Tyrol, which is primarily associated with mountains and nature. In this region in the North of Italy, more than 7,000 apple growers produce 10% of all European apples. Conventional apple cultivation relies primarily on synthetic pesticides, which are applied by fan-assisted sprayers: insecticides to combat pests such as the codling moth and fungicides against fungal diseases that cause scabs on the fruit. This results in a high level of drift into the environment, especially in windy conditions.

For a long time, even experts assumed that the synthetic pesticides essentially remained in the apple orchard where they were applied and could only be found in the immediate vicinity. However, this assumption is based on outdated and less sensitive measurement methods and the fact that pesticides away from the production areas were simply not recorded, according to environmental scientist Carsten Brühl from the RPTU in Landau.

With today's modern analytical methods, up to 100 pesticides can be measured simultaneously, even in low concentrations. In fact, studies show that pesticides spread well beyond agricultural land and affect insects in nature reserves or can be found in the ambient air far away from agriculture.

In the Venosta Valley, a decline in butterflies in mountain meadows was observed several years ago. Experts suspected a connection with the use of pesticides in the valley, but there are hardly any studies on the question of how far current pesticides are actually transported and how long they remain in the soil and plants.

This prompted Brühl and his colleague Johann Zaller from BOKU to investigate the distribution of pesticides in the environment in the Venosta Valley. Their research is published in the journal Communications Earth & Environment.

Measuring pesticide distribution on a landscape scale for the first time

"From an ecotoxicological perspective, the Venosta Valley is particularly interesting, as the valley is characterized by highly intensive cultivation with many pesticides and the mountains are home to sensitive alpine ecosystems, that are in some cases also strictly protected," explains Brühl.

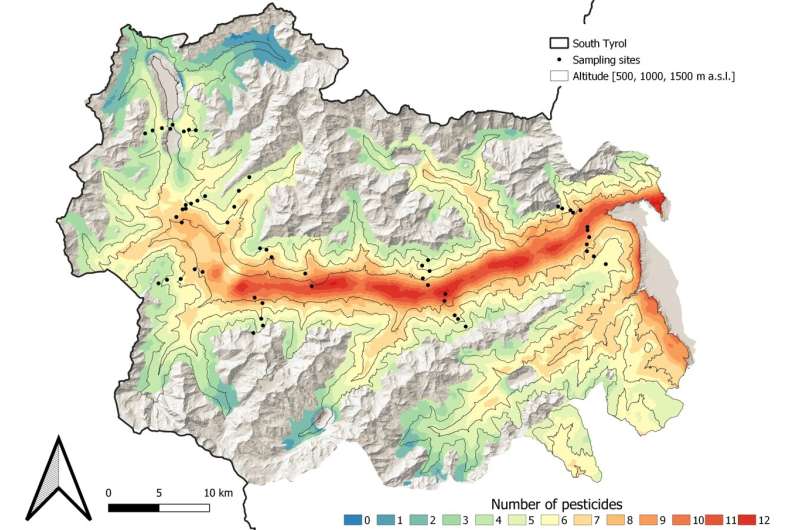

Together with his team and colleagues from BOKU and South Tyrol, he has analyzed pesticide contamination at landscape level—along the entire valley up to high altitudes. Systematically recording and visualizing the fate of pesticides on such a large scale is a first in environmental science.

For their study, the researchers established a total of 11 so-called altitudinal transects along the entire valley axis, stretches that extend from the valley floor at 500 meters above sea level to the mountain peaks above 2,300 meters. The team took samples every 300 meters along these altitudinal transects. Plant material was collected and soil samples taken at a total of 53 locations.

The subsequent analysis showed that although the pesticides decrease overall at higher altitudes and with distance from the apple orchards, the researchers still detected several substances in mixtures in the soil and vegetation, even in the upper Venosta Valley with hardly any apple cultivation.

"We found the substances in remote mountain valleys, on the peaks and in national parks. They have no place there," says Brühl. Due to the sometimes strong valley winds and the thermal updrafts in the Venosta Valley, the substances spread further than one might assume based on their chemical and physical properties.

Even at the low concentrations measured, pesticides can lead to sublethal effects on organisms. For butterflies, for example, this could mean a reduction in egg laying, which then leads to a population reduction. There was only one place where the researchers found no pesticide substances in the vegetation—interestingly, there are also a lot of butterflies in that place.

Almost 30 pesticides detected

The researchers found a total of 27 different pesticides in the environment, but at the same time emphasize that they carried out their measurements at the beginning of May and that further products are used during the growing season up to the harvest. On average, almost 40 applications of pesticides are common during the season. This means that more complex mixtures with several substances and recurring higher concentrations are likely.

In almost half of all soil and plant samples, the researchers were able to measure the insecticide methoxyfenozide, which has not been authorized in Germany since 2016 due to its harmfulness to the environment. Little is known about how chronic exposure to pesticides with mixtures in low concentrations affects the environment, and about the possible interaction of different substances.

In the environmental risk assessment as part of the European authorization procedure, mixtures are not evaluated, but the substances are considered individually. "This has nothing to do with the reality of applications in the field or in the orchard and their fate in the environment," says Brühl.

The researchers are concerned about how widespread the pesticide contamination was in the soil and plants and that even national parks, which were actually set up to protect endangered plants and animals, are exposed. "The concentrations we found were not high, but it has been proven that pesticides affect soil life even at very low concentrations," explains soil expert Johann Zaller from BOKU.

In addition, the team always found a cocktail of different pesticides, the effects of which may be amplified. "The results also show that the technique of pesticide application in apple cultivation is in great need of improvement, otherwise so many pesticides would not be found away from the apple orchards," Zaller is convinced. It is also uneconomical if the pesticides are not applied specifically to the target organisms.

"We know from previous studies that children's playgrounds near apple orchards are contaminated with pesticides. In some cases even throughout the year," says co-author and pesticide critic Koen Hertoge, who lives in the Venosta Valley.

"The current results show a new dimension to the problem, as even remote areas are contaminated with pesticides. Measures to protect nature and the health of the population are absolutely necessary and the new provincial government is now called upon to act."

Promoting functional biodiversity as an alternative to pesticide use

Possible measures would be to reduce or even ban the use of pesticides, at least the substances detected in remote areas, the researchers conclude from their findings. In return, it is important to promote management practices that also encourage beneficial insect-pest interactions, so-called functional biodiversity in the apple orchard and in the surrounding area.

This means, for example, semi-natural and flower-rich grasslands that are distributed across the landscape and provide a habitat for the antagonists of apple pests. In addition, systematic monitoring should be introduced that includes measurements at various locations throughout the year in order to estimate the year-round pesticide input.

According to the researchers, the responsibility for reducing the use of pesticides lies not only with the apple growers, but also with the large supermarket chains: they could promote the acceptance of apples that do not look quite so perfect. This is quite realistic. The fact that people is also critical of the use of pesticides was demonstrated in 2014 by a referendum in the market town of Malles/Mals in the Upper Venosta Valley, where the majority voted against conventional apple cultivation.

Brühl concludes, "We need regions where plants and animals are not contaminated with these bioactive substances. A reduction in pesticides—including large areas without the use of any synthetic pesticide—and the simultaneous expansion of organic farming is urgently needed to reduce landscape pollution. Our results show that it is urgent to act now, unfortunately we have no more time."

More information: Carsten A. Brühl et al, Widespread contamination of soils and vegetation with current use pesticide residues along altitudinal gradients in a European Alpine valley, Communications Earth & Environment (2024). DOI: 10.1038/s43247-024-01220-1

Provided by Rheinland-Pfälzische Technische Universität Kaiserslautern-Landau