This article has been reviewed according to Science X's editorial process and policies. Editors have highlighted the following attributes while ensuring the content's credibility:

fact-checked

trusted source

proofread

Generating cold with solids

After more than a century, physicists aim to dethrone the tried-and-tested technology of the refrigerator, as cooling can be made more energy-efficient.

The summer of 2023 was the hottest on record worldwide. Devastating wildfires raged in many places, and people suffered due to heat records. In a world that is steadily getting warmer, the demand for cooling is rising, too—and cooling consumes energy. A lot of energy.

"As a rule, generating cold is more difficult than generating heat," says Professor Daniel Hägele, physicist at Ruhr University Bochum. The compressor technology used in today's refrigerators was invented more than a century ago. "While the technology has been continuously optimized over the years, recent improvements in energy efficiency classes have mostly involved adjustments like tighter seals on doors," points out the researcher.

It's entirely conceivable to introduce techniques for generating cold that are completely different to those currently in use. The team headed by Daniel Hägele from the Spectroscopy of Condensed Matter working group is studying what is known as the caloric effect: Some solid materials change temperature when stretched or subjected to an electric field or magnetic field.

Solids in an electric field generate cold

Hägele's team has been studying the caloric effect for many years. Initially, the researchers used magnetic fields to generate cold with solids. However, this requires field strengths similar to those in an MRI machine—and could therefore not be implemented in a refrigerator or air conditioner.

This is why Hägele and his colleagues Jörg Rudolph and Jan Fischer are now working with electric fields. "We can basically use power from the socket," says Fischer. "For experimental purposes, we amplify the voltage to several thousand volts."

This is because the Bochum team is interested in special effects. The researchers measure how different materials react to the external electric field, for example changes to temperature. First and foremost, they're interested in time-resolved effects, i.e., how quickly the temperature decreases or increases when the external electric field changes.

"We can detect changes of one-thousandth of a degree in one-thousandth of a second—no one else can do it that fast," says Fischer, describing what makes the Bochum approach so unique.

Being quick pays off

At first glance, it may seem paradoxical that the group is interested in these tiny changes. "We're actually looking for materials with the largest possible temperature effects," admits Hägele. "But sometimes you have to start small." The small changes on the time scale reveal a lot to the researchers about the fundamental processes that lead to temperature changes in solids. Moreover, materials that can quickly change their temperature would be particularly relevant for applications.

"In a caloric cooling process, heat is transported away in packets," explains Jörg Rudolph. "In order to make the process efficient, the best possible approach would be to remove the heat packets quickly one after the other."

Last but not least, rapid measurements also provide an unadulterated view of the material properties. This is because the heating and cooling samples exchange heat with their surroundings over time, for example with the substrate on which they are mounted. If the researchers measure the temperature very quickly, there's no time for heat transfer, and they can measure the pure caloric effect.

But why exactly is the Bochum technique so fast? "Measuring temperature—that may sound simple at first," says Jörg Rudolph. "However, measuring slight temperature variations accurately is a surprisingly complicated process. You can't simply hold a thermometer against the sample." First of all, the sample is much too small, less than a millimeter thick. Secondly, there would be heat exchange between the sample and the thermometer, which would distort the measurements.

Infrared detector as a thermometer

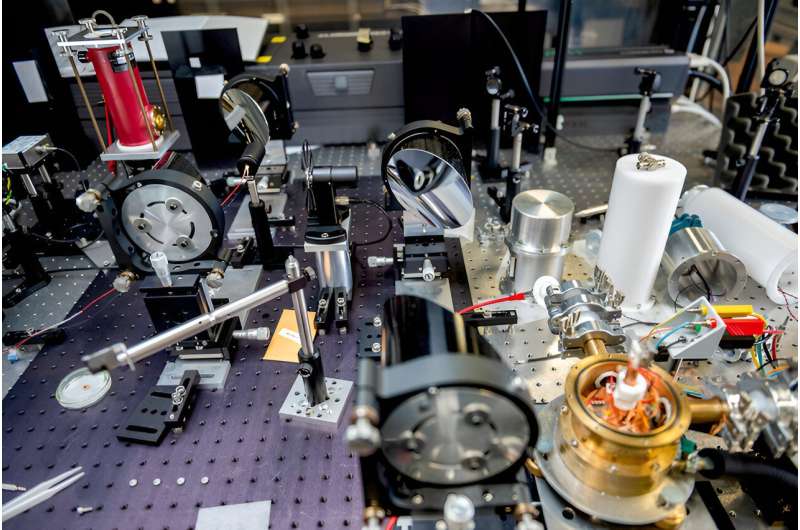

This is why Daniel Hägele devised an experimental setup specifically for these types of measurements several years ago, which his team has now optimized. They deploy a contactless infrared detector to measure the heat energy emitted by the sample. The experimental setup is located in a climate-controlled room on a vibration-stabilized table—a piece of equipment that was rather tricky to install.

"The table weighs a ton, so we couldn't simply put it in the elevator. To get it into the lab, we had to remove two windows and have it hoisted in with a crane," tells us Daniel Hägele. "Also, it has to stand in a specific spot in the room so that it doesn't come crashing through the floor," adds Jörg Rudolph.

Measuring several material properties simultaneously

The setup has now been securely installed in the lab for years, and Hägele, Rudolph and Fischer have used it to measure a number of materials. In addition to measuring rapid temperature changes, they can at the same time capture a second material property in the solids, namely polarization—another aspect that makes the Bochum setup unique. This is useful because highly polarizable materials offer advantages for the generation of cold.

In addition to established materials such as the rare earth gadolinium and various metal alloys, the researchers from Bochum are also exploring other material classes like ceramics and plastic polymers, as these categories have also produced promising candidates. In the process, they focus on environmentally friendly and non-toxic materials.

Some of these have already been used by other groups to build demonstrators. "It's awesome that our fundamental research has such a tangible application," says Jörg Rudolph. "That's a powerful motivator."

Cooling based on the caloric effect is a multi-stage process. Typically, a material can only achieve a cooling of three to four, at most 6°C in one go. However, a cooling system could consist of multiple chambers, providing cooling by a few degrees at the spots where they connect, thus achieving a significant cooling effect overall.

Many feasible applications

Unlike with conventional refrigerators, cold would no longer be generated using a gas or liquid but a solid material. "The advantage of using a solid material is that it contains more atoms per cubic centimeter," explains Hägele. "This would allow us to build more compact cooling appliances." And potentially more efficient ones, too.

This could be useful not only for refrigerators and air conditioning systems but also, for example, for hydrogen liquefaction. There would certainly be plenty of applications in a world that is getting warmer and warmer.

Provided by Ruhr-Universitaet-Bochum