This article has been reviewed according to Science X's editorial process and policies. Editors have highlighted the following attributes while ensuring the content's credibility:

fact-checked

peer-reviewed publication

trusted source

written by researcher(s)

proofread

We need a single list of all life on Earth, and most taxonomists now agree on how to start

Species lists are one of the unseen pillars of science and society. Lists of species underpin our understanding of the natural world, threatened species management, quarantine, disease control and much else besides.

The people who describe new species and create lists of them are taxonomists. A few years ago, a headline in the journal Nature accused the taxonomic community of anarchy for not coordinating a common view of species, leading to confusion about our knowledge of life on earth.

Many in the taxonomic community took umbrage at this. Taxonomists were concerned that the ideas proposed would limit their freedom of expression and they would be tied to a bureaucracy before they could publish new species descriptions.

Taxonomists certainly argue—disputation is essential to the practice of taxonomy, as it is to science in general. Ultimately, however, a taxonomist's life is spent trying to discern order in the extraordinarily diverse tree of life.

The results of a new survey published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, show just how much taxonomists really do like order.

Hardly a group of anarchists

The argument was about how to solve disagreements between taxonomists. Eventually, the two sides came together to produce principles on the creation of a single authoritative list of species.

This group then went to the taxonomic community to survey their views on whether a global species list is needed and how it should be run.

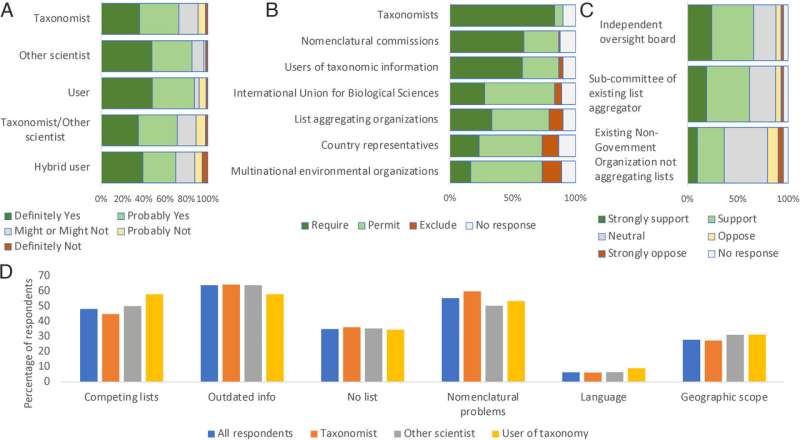

The newly published results show that a large majority (77%) of respondents—which included more than 1,100 taxonomists and users of taxonomy across 74 countries—have expressed support for having a single list of all life on Earth.

They also agreed there should be a governance system that supports the list's creation and maintenance. Just what that governance system would entail is not yet specified. Deciding that will be the next step in the process.

Taxonomists propose hypotheses, not facts

Why is this important? Many may not realize that when a taxonomist names a new species description, they are proposing a scientific hypothesis, not presenting an objective scientific fact.

Other taxonomists then look at the evidence provided in the description and decide whether they agree. If people making species lists judge that there is agreement about a hypothesis, the new species goes on their list.

Only after a species is listed can it be protected, studied, eradicated, ignored or whatever else governments decide is appropriate. Scientists and conservation advocates also need species to be listed before they can include them in their work. Until listed, the species remains, for all practical purposes, invisible.

However, not all lists are equally trusted. Very rarely taxonomists do go rogue. One notorious taxonomist has been blacklisted for "taxonomic vandalism." He published all sorts of new names—some even commemorated his dog—with little justification. If accepted, his field (herpetology) would have been thrown into chaos.

The work of rogue taxonomists wastes everyone's time and money. In one instance, poor taxonomy has even killed people—an antivenom labeled with the wrong name for a snake was distributed in Africa and Papua New Guinea with disastrous results.

Even without rogue taxonomists, there is an enormous problem with so-called synonyms—different people giving different names for the same species. Some species have tens of scientific names, not to mention misspellings.

This leaves users uncertain what name to use. Sometimes they use different names but mean the same species; sometimes the same names but mean different species. The only way to clarify this confusion is by having a working master list of species names linked to the scientific literature.

Now what?

The newly released survey shows taxonomists and users of taxonomy have achieved an agreement that good lists need good governance. Species lists need to reflect the best science, independent of outside influence. They need dispute resolution processes. And they need involvement and agreement from the taxonomic community on their contents.

Governance of science does not work unless a large majority of scientists agree with the rules, because participation is voluntary. There's no such thing as science police.

Agreement and compliance is best achieved if scientists themselves are involved in the creation of the rules. This helps to increase buy-in among the community of peers to make sure rules are kept.

Based on the survey results, the Catalogue of Life—the group that has the most comprehensive global species list to date, and the one we're involved in—is piloting ways of measuring the quality of the lists that make up their catalogue.

These are being trialed first with the creators of lists, everything from viruses to mammals. Then, they will be tested with the taxonomic community at large for further feedback.

Good taxonomy is far more valuable than people realize. One recent study in Australia found that, for every dollar spent on taxonomy, the economy gained A$35. The value of taxonomy globally is likely to be colossal.

But the value will be higher still if everyone the world over is able to use the same list of species.

More information: Aaron M. Lien et al, Widespread support for a global species list with a formal governance system, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (2023). DOI: 10.1073/pnas.2306899120

Journal information: Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences , Nature

Provided by The Conversation

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.![]()