This article has been reviewed according to Science X's editorial process and policies. Editors have highlighted the following attributes while ensuring the content's credibility:

fact-checked

peer-reviewed publication

trusted source

proofread

Large sub-surface granite formation signals ancient volcanic activity on moon's dark side

A large formation of granite discovered below the lunar surface likely was formed from the cooling of molten lava that fed a volcano or volcanoes that erupted early in the moon's history—as long as 3.5 billion years ago.

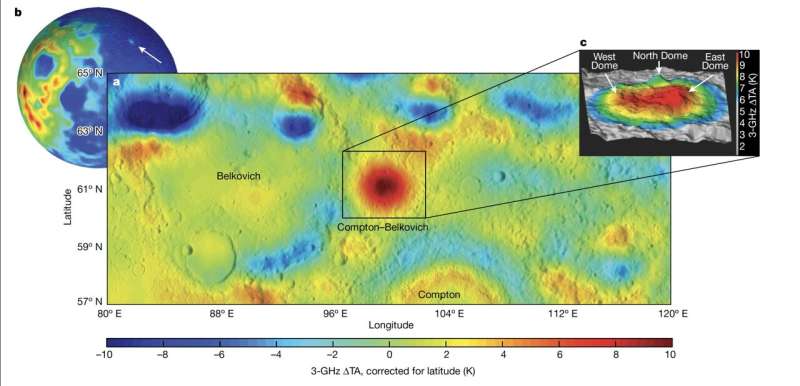

A team of scientists led by Matthew Siegler, an SMU research professor and research scientist with the Planetary Science Institute, has published a study in Nature that used microwave frequency data to measure heat below the surface of a suspected volcanic feature on the moon known as Compton-Belkovich. The team used the data to determine that the heat being generated below the surface is coming from a concentration of radioactive elements that can only exist on the moon as granite.

Granites are the igneous rock remnants of the plumbing systems below extinct volcanos. The granite formation left when lava cools without erupting is known as a batholith.

"Any big body of granite that we find on Earth used to feed a big bunch of volcanoes, much like a large system is feeding the Cascade volcanoes in the Pacific Northwest today," Siegler said. "Batholiths are much bigger than the volcanoes they feed on the surface. For example, the Sierra Nevada mountains are a batholith, left from a volcanic chain in the western United States that existed long ago."

The lunar batholith is located in a region of the moon previously identified as a volcanic complex, but researchers are surprised at its size, with an estimated diameter of 50 kilometers.

Granite is somewhat common on Earth, and its formation is generally driven by water and plate tectonics, which aid in creating large melt bodies below the Earth's surface. However, granites are extremely rare on the moon, which lacks these processes.

Finding this granite body helps explain how the early lunar crust formed.

"If you don't have water it takes extreme situations to make granite," Siegler said. "So, here's this system with no water, and no plate tectonics—but you have granite. Was there water on the moon—at least in this one spot? Or was it just especially hot?"

More information: Matthew Siegler, Remote detection of a lunar granitic batholith at Compton–Belkovich, Nature (2023). DOI: 10.1038/s41586-023-06183-5. www.nature.com/articles/s41586-023-06183-5

Journal information: Nature

Provided by Southern Methodist University