This article has been reviewed according to Science X's editorial process and policies. Editors have highlighted the following attributes while ensuring the content's credibility:

fact-checked

peer-reviewed publication

trusted source

proofread

Body part regeneration appears to be a whole-body affair

A mouse injured on one leg experiences an "awakening" of stem cells in the other leg as if the cells are preparing to heal an injury. Something similar happens in axolotls, which are masters at limb regeneration. Heart injuries in zebrafish can trigger certain changes in far-away organs like the kidney and brain.

"In many different organisms, you can see the whole body respond to an injury. But whether or not those responses actually have any function has been unclear," says Bo Wang, assistant professor of bioengineering at Stanford, "So that's what we're focusing on."

In a new paper published in the journal Cell, Wang and his colleagues have found that this whole-body coordination is a crucial part of wound healing and subsequent tissue regeneration in planarian worms. Understanding what turns regeneration on and off, and how it's coordinated, also informs studies of cancer, which is often thought of as wounds that never heal.

Worm waves

Planarians are half-inch-long flatworms with a superpower: they can regrow in almost any scenario. Cut a planarian into four pieces, and a few days later you've got four new flatworms. Like mice, zebrafish, and axolotls, wounds in one part of a planarian's body seem to trigger responses in more distant tissues.

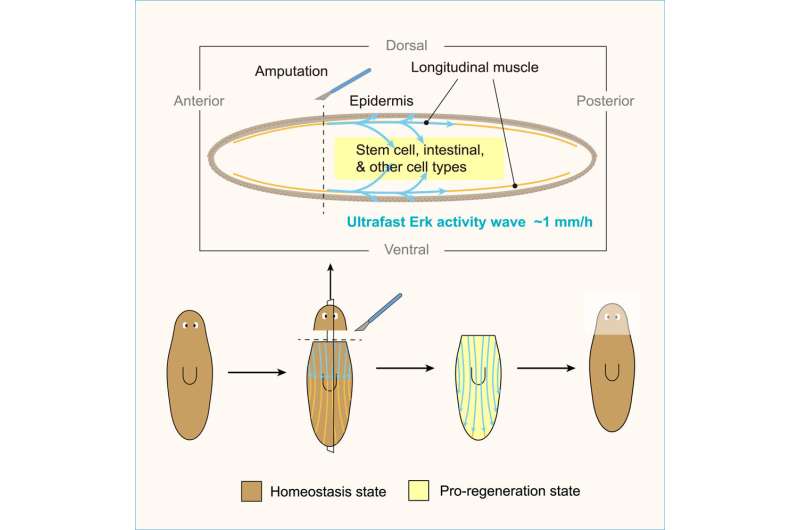

Wang wanted to understand how these responses were coordinated. One possible mechanism is the extracellular signal-related kinase (ERK) pathway. Cells use the ERK pathway to communicate with each other, and send signals out in a sort of wave. If tissue is injured, the nearest cells "pass on" that information to their neighboring cells, which then tell their neighbors. This wave propagates throughout the organism in a kind of telephone game.

There's just one problem: past research has shown that ERK waves move too slowly to be of any use. "If I propagate a signal at 10 microns per hour, it can take days to go through one millimeter," Wang says. At that speed, it is far too slow for a signal to get from one area of the worm to another in order to aid in wound healing and regeneration.

That may not be an issue in humans. Our circulatory system may let signals spread quickly throughout our body. But planarians don't have a circulatory system to speed up the process.

So Wang and his colleagues began tracking the ERK waves as they traveled from one end of the animal to another. They found signals traveling over 100 times faster than previously seen. Instead of traveling in small steps from cell to cell, the ERK waves traveled along extra-long body-wall muscle cells. These cells which acted as "superhighways," accelerate the signal from one end of the body to another. Instead of days, it took hours.

The signal was fast enough to aid in healing, but they still didn't know if the whole body was involved.

To find out, Yuhang Fan, a graduate student in the Wang lab, cut off a planarian's head.

Voting to grow

Normally, the planarian head quickly regrows from the remaining body after decapitation. But Fan blocked the ERK signal from spreading to the back half of the organism to test whether ERK waves were responsible for coordinating the distanced healing response.

When the ERK signals were blocked, the head didn't just heal slower: it never regrew at all.

Next, Fan wanted to know if it was possible to "rescue" the regeneration process, and tested this by removing the planarian's tail, too, which alerts the tail tissue that there is an injury. The tail regrew, and, astonishingly, the head grew back as well.

"What's really interesting is that we can tune the time delay between the two amputations," says Wang. If you cut off a planarian's tail just a few hours after the initial injury, you can restart the blocked healing process. But if you wait too long, neither regrows.

"This implies there's kind of a global body voting system that says, 'Okay, now we should grow something,' and everybody has to agree," says Wang. And even the cells furthest away get a vote.

Healing for humans

Many animals—like planarians, sea stars, and axolotls—exhibit healing and regenerative ability far beyond that of humans. Understanding why we lack such abilities could lead to advances in medical treatments and interventions, including implications related to cancer.

"You don't want tissues in a wounded state all the time. That may cause cancer," explains Wang. Even in these spectacularly regenerative worms, Wang's research reveals that most of the time, regeneration is turned "off," until the whole body agrees that it's time to turn "on."

Additionally, as Wang and his colleagues tracked ERK waves spreading throughout planarians' bodies, they noted that hundreds of genes were turned on and off. Although humans are only very distantly related to planarians, we share many of those same genes.

"This really gives us an entryway to go after those genes," says Wang. "It could allow us to figure out how animals regenerate while managing the risk of uncontrolled cancerous growth."

More information: Yuhang Fan et al, Ultrafast distant wound response is essential for whole-body regeneration, Cell (2023). DOI: 10.1016/j.cell.2023.06.019

Journal information: Cell

Provided by Stanford University