This article has been reviewed according to Science X's editorial process and policies. Editors have highlighted the following attributes while ensuring the content's credibility:

fact-checked

peer-reviewed publication

trusted source

proofread

Aquatic animals living closer to the edge when it comes to heat stress: Study

Amphipods have a much smaller safety margin to cope with warmer water in rivers than has been recognized previously. They also need to get used to warmer water gradually. This is shown by the research of Wilco Verberk of Radboud University and ecologists. The work is published in the journal Global Change Biology.

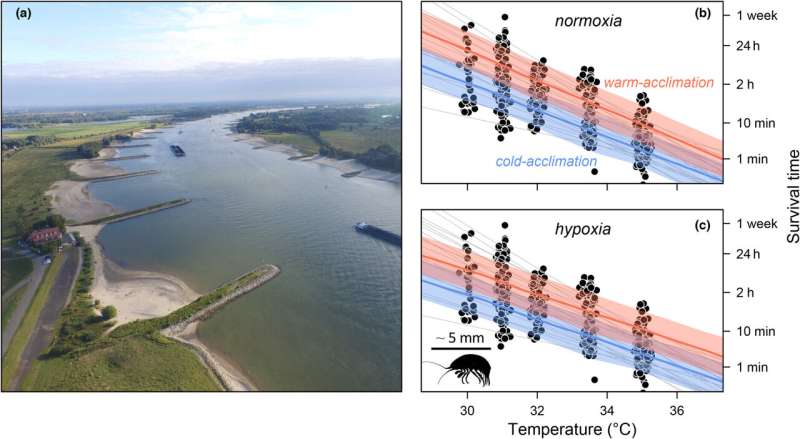

The study presents a new method for measuring the heat tolerance of animals, which makes it easier to link the lab with fieldwork. Verberk states, "Heat tolerance is often measured by taking the animals out of the water and into the lab, exposing them to increasingly warmer water for one to two hours and determining the temperature at which they start to die." For the amphipod species in this study, that was about 34 degrees.

"Our rivers are usually not warmer than 27 degrees, so it was assumed that there was a safety margin of 7 degrees before the animals die. But the short time period may overestimate things: humans can easily handle an hour in the sauna for example, but we shouldn't stay in there all day."

Acclimation

Verberk studied how well amphipods can deal with extreme heat on timescales beyond a few hours. In the new approach, survival is expressed as a survival probability, rather than as a critical temperature. "Mathematically, probabilities are much more flexible, allowing easy calculations on what happens over a longer period of time."

It appeared that the comfortable 7°C safety margin quickly evaporates when you calculate survival over periods of weeks rather than hours. Moreover, it made a big difference if the animals had previously been acclimated to warm or cold water and whether they were housed in well oxygenated water or water that was oxygen depleted.

"Like all other cold-blooded animals, amphipods need more oxygen for their metabolism when they're in warm water. So the amphipods could cope better with extreme heat if they had previously been acclimated to conditions when they need more oxygen (i.e., warm water) or when extracting oxygen is difficult (oxygen-poor water)," states Verberk.

It was already known that extreme heat is stressful to amphipods. However, the researchers demonstrated that it is not just about temperature. Time is also an important factor: the longer amphipods have to tolerate heat, the more stressful it is.

"So you can't simply express heat tolerance in terms of a certain threshold temperature; you also have to consider the time and the amount of oxygen in the water. The new approach was applied to calculate survival probabilities from actual data from Rijkswaterstaat, the executive agency of the Ministry of Infrastructure and Water Management. This data includes fluctuations in water temperature and oxygen levels," says Verberk.

New approach

The researchers' findings are relevant for calculations about what riverine animals, not just amphipods, can handle. Which temperatures and oxygen levels can they cope with and which ones will prove lethal? Verberk's calculations show that death due to heat stress in rivers is now perhaps manageable, but in 100 years—if temperatures continue to rise because of climate change—it could increase by 60% to 100%.

"This new way of calculating can be useful if we want to protect certain sorts of animals. We now have a better idea of when temperatures become critically warm for animals in the field. In the lab we often work with short trials where animals didn't have time to get used to it, which does not reflect the reality in the field.

"We can now take action more quickly by, for example, doing something about the oxygen level in the water. Global warming is challenging to combat, partially because it occurs at the global level, but water quality can be improved by taking action at the regional level."

More information: Wilco C. E. P. Verberk et al, Long‐term forecast of thermal mortality with climate warming in riverine amphipods, Global Change Biology (2023). DOI: 10.1111/gcb.16834

Journal information: Global Change Biology

Provided by Radboud University