This article has been reviewed according to Science X's editorial process and policies. Editors have highlighted the following attributes while ensuring the content's credibility:

fact-checked

peer-reviewed publication

proofread

Re‐examining the underground connections between trees

Fungal networks interconnecting trees in a forest is a key factor that determines the nature of forests and their response to climate change. These networks have also been viewed as a means for trees to help their offspring and other tree-friends, according to the increasingly popular "mother tree hypothesis." An international group of researchers re-examined the evidence for and against this hypothesis in a new study.

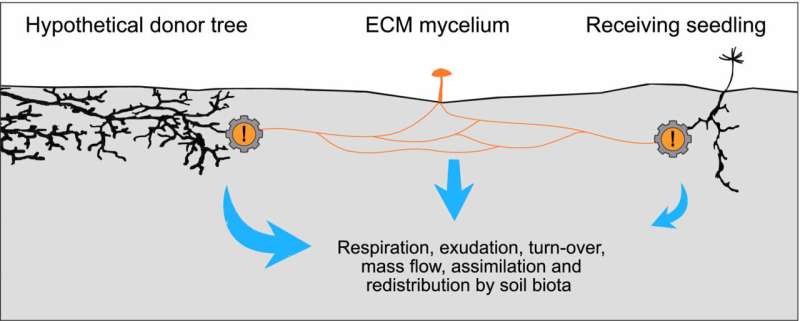

Trees in a forest are interconnected through thread-like structures of symbiotic fungi, called hyphae, which together form an underground network called a mycorrhizal network. While it is well known that the mycorrhizal fungi deliver nutrients to trees in exchange for carbon supplied by the trees, the so-called mother tree hypothesis implies a whole new purpose of these networks.

Through the network, the biggest and oldest trees, also known as mother trees, share carbon and nutrients with the saplings growing in particularly shady areas where there is not enough sunlight for adequate photosynthesis.

The network structure should also enable mother trees to detect the ill health of their neighbors through distress signals, alerting them to send these trees the nutrients they need to heal. In this way, mother trees are believed to act as central hubs, communicating with both young seedlings and other large trees around them to increase their chances of survival.

This is a very appealing concept attracting the attention of not only scientists, but also the media, where this hypothesis is often presented as fact. According to the authors of the study just published in New Phytologist, the hypothesis is however hard to reconcile with theory, prompting the researchers to re-examine data and conclusions from publications for and against the mother tree hypothesis.

The study, led by Nils Henriksson at the Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences, found that the empirical evidence for the mother tree hypothesis is actually very limited and theoretical explanations for the mechanisms are largely lacking.

While big trees and their interconnections with their neighbors are still essential for the forest ecosystem, the fungal network does not work as a simple pipeline for resource sharing among trees. This means that apparent resource sharing among trees is more likely to be a result of trading between fungi and trees rather than directed transfer from one tree to another. Very often, this even results in aggravated competition between trees rather than support of seedlings.

"We found that mycorrhizal networks are indeed essential for the stability of many forest ecosystems, but rarely through sharing and caring among trees. Rather, it works like a trading ground for individual trees and fungi, each trying to make the best deal to survive," explains Oskar Franklin, a study author and a researcher in the Agriculture, Forestry, and Ecosystem Services Research Group of the IIASA Biodiversity and Natural Resources Program.

"The forest is not a super organism or a family of trees helping each other. It is a complex ecosystem with trees, fungi, and other organisms, which are all interdependent but not guided by a common purpose."

"Although the narrative of the mother tree hypothesis is scarcely supported by scientific evidence and is controversial in the scientific community, it has inspired both research and public interest in the complexity of forests. It is vital that the future management and study of forests take the real complexity of these important ecosystems into account," Franklin concludes.

More information: Nils Henriksson et al, Re‐examining the evidence for the mother tree hypothesis—resource sharing among trees via ectomycorrhizal networks, New Phytologist (2023). DOI: 10.1111/nph.18935

Journal information: New Phytologist

Provided by International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis (IIASA)