This article has been reviewed according to Science X's editorial process and policies. Editors have highlighted the following attributes while ensuring the content's credibility:

fact-checked

peer-reviewed publication

trusted source

proofread

Cell membrane 'blebs' could hold new targets for anti-cancer drugs

Cell membrane protrusions called blebs that typically signify the end of life for healthy cells do the opposite for melanoma cells, activating processes in these cells that help them to survive and spread, a UT Southwestern study suggests. The findings, published in Nature, could lead to new ways to fight melanoma and potentially a broad range of other cancers. A News and Views article in the same journal discusses the research.

"Our old adage in biology is that form follows function. But here, we're flipping that concept on its head. By changing the form, we're showing that you can change chemical processes inside the cell that control their functions," said Gaudenz Danuser, Ph.D., chair of the Lyda Hill Department of Bioinformatics and Professor of Cell Biology at UTSW. Dr. Danuser co-led the study with Andrew D. Weems, Ph.D., an Instructor of Bioinformatics and in the Danuser lab.

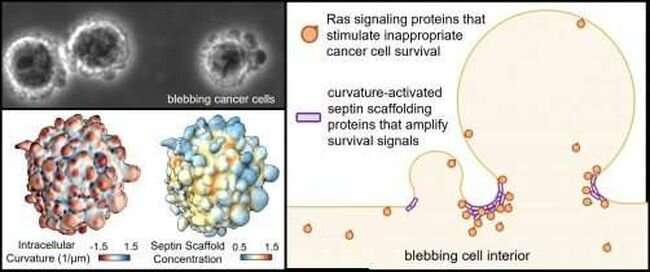

Dr. Weems explained that healthy cells that separate from larger tissues face almost certain death through a process called anoikis unless they can reattach within hours. However, one hallmark of malignant cells is their ability to stay alive indefinitely once they separate from tumor tissue, allowing them to survive and migrate elsewhere in the body to form metastatic tumors. While detached, they form blebs indefinitely, whereas healthy cells can form blebs only for about an hour after detaching from their tissue of origin.

Previous research in the Danuser lab has shown that blebs collect proteins that can encourage cell survival under stressful conditions. But whether these proteins help cancer cells avoid anoikis and how these proteins are contained in the blebs has been unknown.

These investigations showed that the blebs attracted a family of proteins known as septins, which are drawn to areas of high cell membrane curvature like that found in blebs and form molecular scaffolds that provide a framework for proteins to interact. Here, Dr. Weems said, the septin scaffolds contained Ras proteins, which regulate cell survival and are mutated in about a fifth of all cancers.

When the researchers treated melanoma cells with a compound that inhibits septins, called forchlorfenuron (FCF), the septins could no longer scaffold Ras proteins, resulting in an inability of the cells to sustain the chemical reactions that were keeping them alive. Hence they died when they became detached from other cells, which is identical to the fate of healthy cells. Conversely, when they introduced mutations that caused healthy cells to form blebs for longer than usual, these cells became as anoikis-resistant as cancer cells, even though these cells did not harbor cancerous Ras mutations.

"These findings show that 'so-called' oncogenic mutations alone are not sufficient to drive cancer functions, but that they may depend on specific cellular configurations to do so," said Dr. Danuser, a member of the Harold C. Simmons Comprehensive Cancer Center at UTSW and Cancer Prevention and Research Institute of Texas (CPRIT) Scholar. "On the other hand, promoting these cellular configurations alone can enable cancer-generating functions in perfectly healthy cells with no mutations. This offers a fundamentally new perspective of cancer development."

Dr. Weems said researchers have tried for decades to inhibit Ras activity without success. Ras itself is considered undruggable due to its peculiar molecular structure. By targeting septins instead, he added, researchers may be able to accomplish the same goal, removing cancer cells' ability to resist anoikis and potentially making them more vulnerable to other treatments such as chemotherapy, radiation, or immunotherapy.

"FCF has been used as an agricultural chemical in the U.S. for nearly 20 years, with Environmental Protection Agency data suggesting low toxicity for humans," Dr. Weems said. "This septin-inhibiting compound and its chemical derivatives could be promising candidates for new anti-cancer therapies."

More information: Andrew D. Weems et al, Blebs promote cell survival by assembling oncogenic signalling hubs, Nature (2023). DOI: 10.1038/s41586-023-05758-6

Michal Reichman-Fried et al, Bleb protrusions help cancer cells to cheat death, Nature (2023). DOI: 10.1038/d41586-023-00477-4

Journal information: Nature

Provided by UT Southwestern Medical Center