US sexually 'teased' its troops in the First World War to make them fight harder, historian claims

The United States Government sought to sexually stimulate then frustrate its soldiers to prepare them for an unpopular conflict in Europe, a Cambridge historian argues.

Recruiting attractive canteen staff; inviting female civilians to closely supervised dances; disseminating alluring propaganda; pressurizing troops to write to women back home; and detaining allegedly promiscuous women to prevent soldiers wasting energy.

These are just some of ways that America's War Department sought to harness pent-up sexual energy to motivate troops in 1918.

At the heart of this experiment was the Commission on Training Camp Activities (CTCA), a War Department-directed umbrella agency. Previous studies have demonstrated that the CTCA sought to control soldiers' and women's sex lives to prevent venereal infection and protect social morality in the US.

The CTCA has been portrayed as one of the last stands of an older generation of moral reformers against the onrush of a liberalizing sexual culture. But Cambridge historian Eric Wycoff Rogers shows that the agency was far more interested in sexuality as a weapon to motivate soldiers to fight.

Motivation

Almost 53,000 American soldiers were killed in the First World War and over 202,000 were wounded.

Initially neutral, the US began to change its position after a German U-boat sank the Lusitania in 1915, and when it was revealed that Germany sought to urge Mexico to attack the United States. But even as their first troops landed in France in June 1917, few Americans fully understood let alone supported this faraway conflict.

In a study published in the Journal of the History of Sexuality, Eric Wycoff Rogers argues that the US Government and military took drastic action to use sexuality to motivate its conscripted soldiers to embrace their roles in the war.

"The war didn't feel relevant to young American men in the way it did to European men," Rogers says.

"Particularly after President Wilson's sudden U-turn on American belligerency, the government had to work hard to convince civilians to support the war, and this was doubly true for soldiers, many of whom were drafted against their will.

"In this context, the War Department actively exploited sexuality to psychologically manipulate American soldiers to fight."

This involved enforcing sexual abstinence while simultaneously exposing soldiers to carefully controlled forms of sexual stimulation. Believing that sexually satisfied men could not be easily motivated, the aim of this teasing was to generate unmet sexual desire, which the War Department could leverage as motivation to fight, especially through appeals to chivalry and heroism.

While earlier historians have covered aspects of the CTCA, Rogers has shown that it was part of a broader morale-building machine that had its own logic. The CTCA was established in April 1917 to get soldiers' sexual behaviors under control as they trained for combat. The Military Morale Section (MMS), which became the Morale Branch at the end of the war, was founded a year later as American Expeditionary Forces were being deployed to Europe.

Led by Edward Lyman Munson, a high-ranking medical officer, the Morale Branch and its predecessor took increasing control over the CTCA.

Drawing on the relatively neglected records of the morale agency, and the writings of the academics and reformers who led it, Rogers shows that these powerful figures believed that sexual climax wasted the energy which fueled a man's motivation. They also believed, however, that stimulating and then diverting a soldier's sex drive could boost his motivation.

Based on this "parasexual logic," as Rogers terms it, these theorists of morale designed a range of manipulative policies and activities that both regulated and stimulated soldiers.

Canteen workers and dances

The YMCA, one of the CTCA's core welfare organizations, strategically recruited attractive female canteen workers to serve troops on both sides of the Atlantic. The selected women, usually in their thirties (and all white), were selected because they were considered to be young enough to be alluring but old enough to resist so-called "khaki fever" and refrain from sexual relations with soldiers.

As Rogers points out, the motivational programs of the morale agencies explains why they did this. Their job was to provide a stimulating but not "dissipating" feminine presence.

Another organization, The War Camp Community Service (WCCS) contributed to the program by hosting chaperoned dances in towns and cities close to training camps in the U.S. These dances were replicated in the designated leave areas for American soldiers in France.

The WCCS sought to prevent "licentious forms of dancing" and other overtly sexual behavior. It also advised that the women and girls in attendance be of the "right sort," a category which excluded nearly all poor and non-white women.

"Dances suddenly went from being a major morality concern for CTCA investigators to becoming a crucial way to motivate soldiers."

Black male soldiers were also excluded from these and other morale agency activities because white military leaders thought they could not be motivated with sex because they were supposedly inherently sexually licentious. For this reason, most Black soldiers were assigned to non-combat units in the First World War.

'Good' and 'bad' women

The effects of the morale programs were not only felt by soldiers, they had a major impact on the lives of thousands of female civilians.

Through the Young Women's Christian Association, the CTCA trained women and girls to support their aims. The CTCA dispatched speakers to cities and towns close to training camps to advise young girls and their mothers on guarding their sexuality from the troops.

At the same time, military and civilian leaders set about extracting sexually active women and girls from areas frequented by soldiers.

"By making sexual opportunities hard to find, the military sought to preserve men's fighting strength," says Eric Wycoff Rogers.

In January 1918, the Surgeon General of the United States urged local and state authorities to step up efforts to arrest civilians who might be carrying a venereal disease. By April, a new "Women and Girls" section of the CTCA was policing and "reforming" those it deemed "sex offenders," a term it reserved for females suspected of having sex outside of marriage, especially with active-duty soldiers.

Thousands of women were arrested, examined under duress and detained during the country's brief involvement in the war.

Rogers says, "One of my key findings is that venereal disease was primarily an excuse to police women and reduce sexual opportunities for soldiers. Morality, too, was a pretext for these programs.

"The real purpose of these horrific measures, however, was fundamentally about maintaining the sexual frustration that kept soldiers motivated."

Propaganda

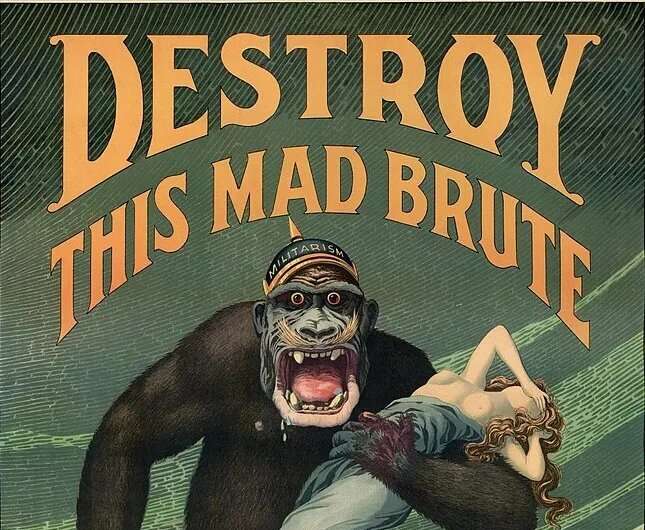

The study reveals that the morale planners became masters of the propaganda directed at soldiers and that in newspapers, lectures and films, they made repeated use of alluring female imagery and voices.

As head of the Morale Branch, Edward Munson acted on a conviction that "Women have a powerful influence on military efficiency and morale." He wrote of the importance of "the girl behind the man behind the gun" and argued that "When women are stirred to patriotic sacrifice, men fear to be slackers."

Drawing on letters and internal memoranda, Rogers demonstrates that the Morale Branch covertly controlled syndicated content in troop newspapers including Trench and Camp and Going Over. At the National Archives in Washington, Rogers also found folders full of edited drafts of the articles that went on to appear in the papers.

"They also engaged in censorship," Rogers says. "In a few instances, the Morale Branch's staff opposed the inclusion of cartoons and other content that they deemed off-message."

The ostensibly YMCA-run Trench and Camp featured letters written by a fictional wife to her enlisted husband. In one of the Letters from a Soldier's Wife, the wife says: "I know you are out on the front, pressing ahead, steadily, grimly … at night when my eyes are closed I have a vision of you, tall and proud, rushing forward."

At the same time soldiers were pressed to write letters to women back home, supported by the provision of free envelopes and paper in YMCA huts and tents. CTCA officials hoped that when soldiers penned their love letters, the presence of attractive canteen workers would act as an exciting proxy for the women they were addressing.

"Sexual denial, status anxiety and perceived pressure from women—this was a powerful combination," Rogers says. "In striving for the approval of women, the morale planners hoped soldiers would perform their duties without complaint, fight harder, and be willing to risk their lives."

The morale planners

The morale program was driven by an elite group of military officers, civilian psychologists and social reformers. In addition to Munson, its leading figures were the pioneering American psychologist G. Stanley Hall, the Harvard philosophy professor and war camp course inspector William Ernest Hocking, and the founder of the Parks and Recreation Association of America—plus war camp activities inspector—Luther H. Gulick.

Each of these men published books arguing that sexual control, paired with the stimulation and re-routing of sexual energy was crucial to motivating soldiers. Unlike traditional moral reformers, they did not seek to suppress sex drive but sought to harness its energy to drive masculine striving.

In his 1921 book The Management of Men, Munson wrote that sexually satisfied soldiers lacked "character" and were less resilient under pressure. But, he argued, the energy behind their sex drive could and should be released through productive activities including military training and "wholesome" leisure activities.

The social reformer Gulick argued that military efficiency depended on sexual control and strongly opposed ejaculation which he compared to "short circuiting an electric current and thus depriving the engine of its power."

Rogers contrasts America's actions with the more laissez-faire approach taken by Britain and France during the war. Their leaders were far more inclined to tolerate—and perhaps even encourage—sexual activity among their soldiers.

After the war

The sudden end of the war did not mark the end of morale or sexualized motivation. After the war, Munson and some of his fellow morale planners published their theories as part of a new focus on human resources management which sought to boost morale and motivation in commercial industries.

The campaigns to police women's sexual behaviors—labeled the "American Plan"—continued for over two decades, with police detaining thousands of women accused of being infected with STDs.

According to Rogers, the spillover of the wartime programs testifies to their enduring significance in modern society, and complicates how we periodize historical eras.

"The idea that America's progressive era reached its crescendo in the First World War, and then was followed by an entirely different period of sexual liberalism in the 1920s is far too simplistic," Rogers says.

"These morale programs reveal a striking hybrid between control and liberation, which suggests a lot more continuity between the two periods, as well as between experiences of constraint and the pursuit of pleasure."

Rogers thinks these insights are highly relevant today.

"The military's 'parasexual' blend of constraint and stimulation offers a clear sketch of a cultural logic that runs deep in American culture: the use of sexual allure to motivate and to sell non-sexual experiences and products."

"Especially if we are going to navigate the tensions of the so-called 'gender war,' we urgently need to understand the role that powerful individuals and organizations continue to play in manipulating sexuality and fuelling sexual frustration, not least in advertising, films and on social media."

More information: Eric Wycoff Rogers, The Men behind the Girl behind the Man behind the Gun: Sex and Motivation in the American Morale Campaigns of the First World War, Journal of the History of Sexuality (2022). DOI: 10.7560/JHS31204

Provided by University of Cambridge