Climate change will increase chances of wildfire globally, but humans can still reduce the risk

New research highlights how the risk of wildfire is rising globally due to climate change—but also, how human actions and policies can play a critical role in regulating regional impacts.

The study, conducted by an international team of researchers led by the University of East Anglia (UEA) in the U.K., shows that anthropogenic climate change is a "push" factor that enhances the risk of wildfires globally.

Fire weather—the hot dry conditions conducive to wildfires—is increasing under climate change, raising the risk of large wildfires by making landscapes more susceptible to burn more often and more severely. The impacts of climate change on fire risk are predicted to escalate in future, with each added degree bringing enhanced wildfire risk.

Climate models suggest that in some world regions, for example the Mediterranean and Amazonia, the frequency of fire weather conditions in the modern period is unprecedented compared with the recent historic climate, due to human induced global warming of around 1.1 degrees Celsius.

More importantly, this will be the case in virtually all world regions if global temperatures reach 2–3 degrees Celsius of warming as per the current trajectory.

Climate models have also shown that the likelihood of some of the most recent and catastrophic wildfires in the western US, Australia and Canada has been significantly greater due to historical climate change.

The article, published today in the journal Reviews of Geophysics, involved scientists from UEA, Swansea University, the University of Exeter and Met Office in the U.K., CSIRO Climate Science Center in Australia, together with colleagues from the U.S., Germany, Spain and the Netherlands.

It explores the relationship between fire trends—past, present and future—and a range of controls on fire activity, including climate but also human activity, land use and changing vegetation productivity, which have with important impacts on the ignition of wildfires and their spread across landscapes.

Lead author Dr. Matthew Jones, of the Tyndall Center for Climate Change Research at UEA, said: "Wildfires can have massive detrimental impacts on society, the economy, human health and livelihoods, biodiversity and carbon storage. These impacts are generally magnified in the case of forest wildfires.

"Clarifying the link between forest wildfire trends and climate change is critical to understanding wildfire threats in future climates. Societies can either push with or pull against the rising risks of fire under of climate change, and regional actions and policies can certainly be important for preventing wildfires or reducing their severity.

"Ultimately, though, we will be fighting the tide of escalating fire risks as the world warms further. Doubling down on efforts to cut greenhouse gas emissions and limiting warming to below 2 degrees Celsius is the most effective thing we can do to avoid the worst risks of wildfire on the global scale."

The authors highlight that humans have important regional effects on wildfire activity in a warming world. For example, they have increased fire ignitions and reduced the natural resilience of some ecosystems to fire, most notably in major tropical deforestation zones of Amazonia and Indonesia.

In contrast, humans have also reduced the spread of wildfire through naturally fire-prone landscapes by converting land to agriculture and fragmenting the natural vegetation, as seen in savannah grasslands in Africa, Brazil and Northern Australia during recent decades.

They can also reduce unwanted ignitions or use firefighting to suppress wildfires, as historically done in forests of the U.S., Australia and Mediterranean Europe. However, the authors say this can have unintended consequences in regions where fire is a natural component of the functioning of ecosystems.

For example, policies that aggressively excluded fire from the western U.S. landscape during the 20th Century resulted in forests that are now overburdened with vegetation fuels, contributing to more severe wildfires during recent droughts. The use of low-intensity fires at times with safe weather conditions is increasingly viewed as an important tool for keeping fuels in check while also facilitating natural ecosystem functions.

Key findings from the analyses include:

- The length of the annual fire weather season has increased by 14 days per year (27%) during 1979–2019 on average globally and the frequency of days with extreme fire weather has increased by 10 days per year (54%) during 1979–2019 on average globally.

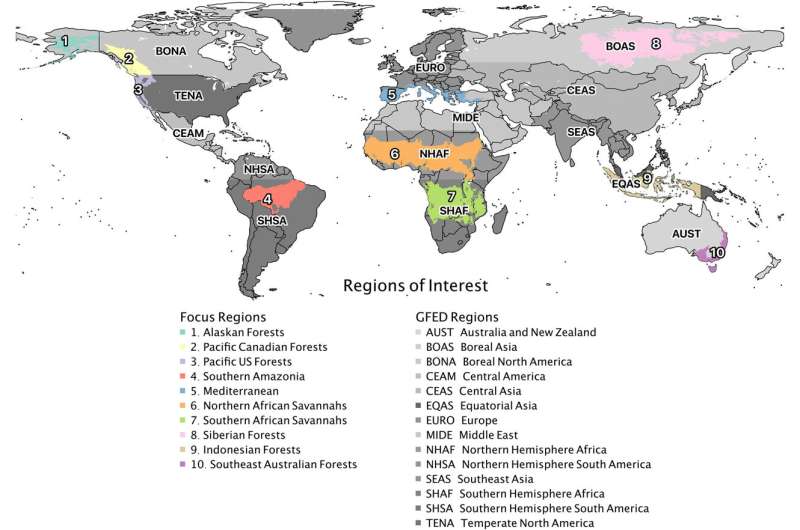

- Fire weather has risen significantly in most world regions since the 1980s. Increases have been particularly pronounced in western North America, Amazonia and the Mediterranean. Fire weather has already emerged beyond its natural variability in the Mediterranean and Amazonia due to historical warming.

- At 2 degrees Celsius this will also be the case in the boreal forests of Siberia, Canada and Alaska and the temperate forests of the western U.S. At 3 degrees Celsius, virtually all world regions will experience unprecedented fire weather.

- Globally, the area burned by fires has decreased by around one-quarter—or 1.1 million km2—during 2001–2019. Much of the decrease—590,000 km2—has been in African savannahs, where 60–70% of the area burned by fire occurs annually. Local/regional human impacts have reduced the area burned by fire in tropical savannahs, in combination with lower grassland productivity during (increasingly drier) wet seasons.

- Large increases in burned area have been observed elsewhere, and especially in temperate and boreal forests. For example, the area burned by fire has increased by 21,400 km2 (93%) in east Siberian forests and by 3,400 km2 (54%) in the forests of western North America (Pacific Canada and US combined).

Co-author Dr. Cristina Santín, from Swansea University and the Spanish National Research Council, added: "Despite the fact that weather conditions promoting wildfire have already increased in nearly in every region the globe and will continue to do so, human factors still mediate or override the climatic ones in many regions.

"We hope this research helps to resolve the entrenched and conflicting views on climate change versus land management being the root cause of these catastrophic fires."

The study assessed 500 previous research papers and carries out a re-analysis of state-of-the-art datasets from satellite observations and models. It includes analyses of trends in fire weather and burned area for world regions covering all countries, continental-scale macroregions, and key regional ecosystems for fire activity or impact.

For these same regions, future changes in fire weather are examined at policy-relevant warming increments of 1.5 degrees Celsius, 2 degrees Celsius, 3 degrees Celsius and 4 degrees Celsius, providing insight into how the success or failure of climate policies correspond to the risks of wildfire we will need to live with in future.

More information: Matthew W. Jones et al, Global and regional trends and drivers of fire under climate change, Reviews of Geophysics (2022). DOI: 10.1029/2020RG000726

Provided by University of East Anglia