Finding additional ways that proteins rotate

Biological materials like bones, teeth, and seashells are impressively tough. This strength comes from their composition: a combination of hard rock-like minerals and resilient carbon-based molecules like proteins. Materials scientists are taking inspiration from these biological materials to create a new generation of advanced materials made from proteins and minerals. But accomplishing this requires understanding how proteins attach and assemble on mineral surfaces.

Proteins are a key type of large, biologically relevant organic molecule, essential to life on earth. In addition to naturally occurring proteins, researchers can custom create proteins with specific characteristics, structures, and properties. This includes designing proteins that can attach to different surfaces, including minerals like mica. Controlling and understanding protein attachment is central to assembling advanced bio-inspired materials.

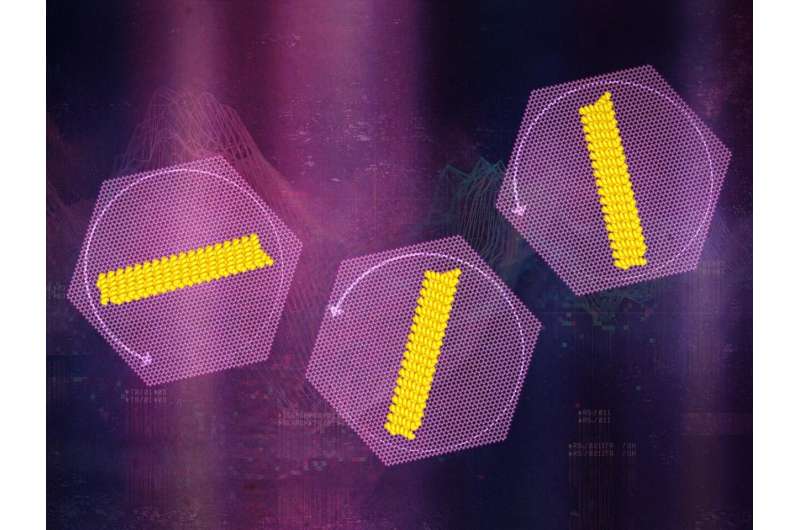

A collaborative team of researchers from Pacific Northwest National Laboratory (PNNL), the University of Washington (UW), and Lawrence Berkley National Laboratory (Berkley Lab) worked to track how specially designed protein nanorods moved on a mica surface, which was recently published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Science. Through collaboration with the Institute for Protein Design at UW, the team developed a series of different-sized protein nanorods specifically created to bind to mica. They then used high-speed microscopy to watch individual nanorods rotate in real-time.

"We were able to track the protein nanorods at unprecedented levels of resolution," said Shuai Zhang, a Research Assistant Professor in the Department of Materials Science & Engineering at UW who has a joint appointment with PNNL. "The atomic force microscope we used is incredibly powerful, allowing us to see individual molecule movements in real-time."

To accurately observe protein rotation, the researchers had to study the protein-mica system in water. This environment mimics the conditions of protein assembly on real mineral surfaces.

Understanding different motion

Observing the system under a microscope produced massive quantities of data. The sheer volume of data made it challenging to analyze. The team at Berkley Lab solved that problem by developing a new machine-learning algorithm that dramatically decreased the time needed to process the images. From there, the researchers were able to look at how fast the proteins moved and how far they were rotating per individual move.

Their observations showed that the proteins mostly behaved as expected, i.e., moved by making small jumps, following a model of motion traceable back to Einstein. However, the proteins occasionally made large, rapid jumps that the model couldn't explain.

To get to the bottom of these different types of motion, the team performed simulations based on the microscopy data. They found that the energy of the protein-surface bond controlled how the proteins could rotate. Most of the time the proteins remain strongly bound to the mica surface, only able to make small motions. Occasionally they appear to briefly detach from the mica. During those short periods of time, the proteins can move quickly in large jumps.

"Comparing our observational data and simulations allowed us to identify both types of protein motion," said Ben Legg, a chemist at PNNL. "We think that the large jumps have important consequences for assembling protein-mineral structures."

Understanding how individual biological molecules move can help researchers develop better methods to assemble large number of proteins on surfaces.

More information: Shuai Zhang et al, Rotational dynamics and transition mechanisms of surface-adsorbed proteins, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (2022). DOI: 10.1073/pnas.2020242119

Provided by Pacific Northwest National Laboratory