Researchers capture first 3D super-resolution images in living mice

Researchers have developed a new microscopy technique that can acquire 3-D super-resolution images of subcellular structures from about 100 microns deep inside biological tissue, including the brain. By giving scientists a deeper view into the brain, the method could help reveal subtle changes that occur in neurons over time, during learning, or as result of disease.

The new approach is an extension of stimulated emission depletion (STED) microscopy, a breakthrough technique that achieves nanoscale resolution by overcoming the traditional diffraction limit of optical microscopes. Stefan Hell won the 2014 Nobel Prize in Chemistry for developing this super-resolution imaging technique.

In Optica, the researchers describe how they used their new STED microscope to image, in super-resolution, the 3-D structure of dendritic spines deep inside the brain of a living mouse. Dendric spines are tiny protrusions on the dendritic branches of neurons, which receive synaptic inputs from neighboring neurons. They play a crucial role in neuronal activity.

"Our microscope is the first instrument in the world to achieve 3-D STED super-resolution deep inside a living animal," said leader of the research team Joerg Bewersdorf from Yale School of Medicine. "Such advances in deep-tissue imaging technology will allow researchers to directly visualize subcellular structures and dynamics in their native tissue environment," said Bewersdorf. "The ability to study cellular behavior in this way is critical to gaining a comprehensive understanding of biological phenomena for biomedical research as well as for pharmaceutical development."

Going deeper

Conventional STED microscopy is most often used to image cultured cell specimens. Using the technique to image thick tissue or living animals is a lot more challenging, especially when the super-resolution benefits of STED are extended to the third dimension for 3-D-STED. This limitation occurs because thick and optically dense tissue prevents light from penetrating deeply and from focusing properly, thus impairing the super-resolution capabilities of the STED microscope.

To overcome this challenge, the researchers combined STED microscopy with two-photon excitation (2PE) and adaptive optics. "2PE enables imaging deeper in tissue by using near-infrared wavelengths rather than visible light," said Mary Grace M. Velasco, first author of the paper. "Infrared light is less susceptible to scattering and, therefore, is better able to penetrate deep into the tissue."

The researchers also added adaptive optics to their system. "The use of adaptive optics corrects distortions to the shape of light, i.e., the optical aberrations, that arise when imaging in and through tissue," said Velasco. "During imaging, the adaptive element modifies the light wavefront in the exact opposite way that the tissue in the specimen does. The aberrations from the adaptive element, therefore, cancel out the aberrations from the tissue, creating ideal imaging conditions that allow the STED super-resolution capabilities to be recovered in all three dimensions."

Seeing changes in the brain

The researchers tested their 3-D-2PE-STED technique by first imaging well-characterized structures in cultured cells on a cover slip. Compared to using 2PE alone, 3-D-2PE-STED resolved volumes more than 10 times smaller. They also showed that their microscope could resolve the distribution of DNA in the nucleus of mouse skin cells much better than a conventional two-photon microscope.

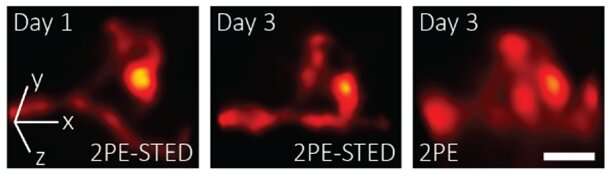

After these tests, the researchers used their 3-D-2PE-STED microscope to image the brain of a living mouse. They zoomed-in on part of a dendrite and resolved the 3-D structure of individual spines. They then imaged the same area two days later and showed that the spine structure had indeed changed during this time. The researchers did not observe any changes in the structure of the neurons in their images or in the mice's behavior that would indicate damage from the imaging. However, they do plan to study this further.

"Dendritic spines are so small that without super-resolution it is difficult to visualize their exact 3-D shape, let alone any changes to this shape over time," said Velasco. "3-D-2PE-STED now provides the means to observe these changes and to do so not only in the superficial layers of the brain, but also deeper inside, where more of the interesting connections happen."

More information: Mary Grace Velasco et al, 3D super-resolution deep-tissue imaging in living mice, Optica (2021). DOI: 10.1364/OPTICA.416841

Journal information: Optica

Provided by The Optical Society