Using better colours in science

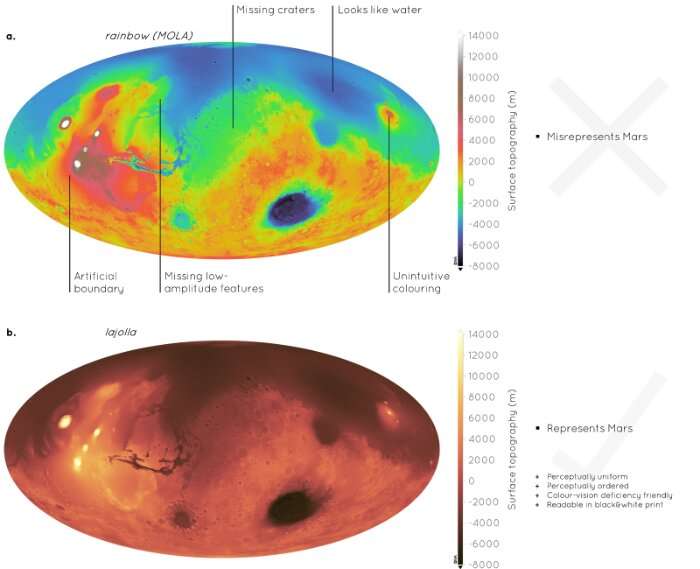

Colors are often essential to convey scientific data, from weather maps to the surface of Mars. But did you ever consider that a combination of colors could be "unscientific?" Well, that's the case with color scales that use rainbow-like and red–green colors, because they effectively distort data. And if that was not bad enough, they are unreadable to those with any form of color blindness. Researchers from the University of Oslo and Durham University explain scientific color maps, and present free-to-download and easy-to-use solutions in an open-access paper released today in Nature Communications.

The use of the full rainbow of colors is pervasive in science and common daily societal data such as weather maps and hazard warnings. For many years, the default coloring option in software programs was the rainbow-like "jet," and many people simply seem attracted to the array of colors that a rainbow offers.

"Rainbows are fantastic," explains lead author Fabio Crameri, "but in the context of displaying scientific, technical, medical or similar such data, it needs to be stopped." This is because the properties of the colors, and the way that the human eye understands them can lead to distortion. It is therefore not just a problem for scientists, but also for journal editors, visual communicators, journalists, administrators and society at large.

Two such properties that can cause distortion are (non-)perceptual uniformity and order. These essentially refer to the color and lightness change, and an intuitive color order, respectively. For example, a scale should generally start (or end) with a lighter shade at one end and smoothly change to a darker shade at the other. This can involve different colors (or hues) but should meet the lightness/brightness criteria. Naturally, some datasets will need different coloring options than others (e.g. sequential or diverging data)—but they should still meet the perceptual uniformity and other scientific criteria as much as possible.

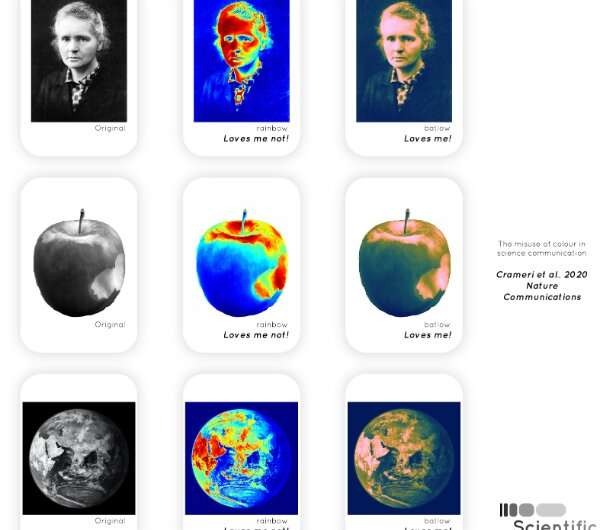

A simple test is to think of printed the results in black and white—would it be possible to tell the difference between the high and low parts of the data? Another example is taking a well-known image, such as a person, in black and white and comparing it to what it looks like in a rainbow map ('jet'), a scientific alternative ('batlow'). It is clear that the scientific alternative batlow does a much better job than the rainbow jet to recover the original image.

Another major reason why unscientific maps should be stamped out is that they are unreadable to those with color blindness—0.5% of women and 8% of men worldwide are estimated to have a form of color vision deficiency. As an example, the modeled trajectory of a hurricane or flood intensity warning are repeat rainbow offenders—but how can those with color vision deficiencies discern this information when displayed with a rainbow-like scale?

There have been several notable efforts by the scientific community to produce scientific coloring options, such as Colorbrewer and CMOcean. Researcher Fabio Crameri is one scientist who has been advocating for the use of scientific color maps and creating free, easy-to-use alternatives for several years. In this latest "Perspective" Nature Communications piece, along with fellow Centre for Earth Evolution and Dynamics (CEED; University of Oslo) colleague Grace Shephard and collaborator Philip Heron at the University of Durham, they explore the color maps, contributions by the community, and present some clear guidelines and resources so that scientific color maps prevail.

More information: Fabio Crameri et al. The misuse of colour in science communication, Nature Communications (2020). DOI: 10.1038/s41467-020-19160-7

Journal information: Nature Communications

Provided by University of Oslo