Cringing at how teens talk? Surprise: Language changes

When USC established El Centro Chicano in 1972 as a resource center for Mexican American students, organizers deliberately chose the word "Chicano" as a point of pride. The term was born out of student protests in the late 1960s during the civil rights movement.

But the center recently made one of the biggest shifts in its 47-year history: It changed its name.

Now called the Latinx Chicanx Center for Advocacy and Student Affairs (or La CASA, for short), the center made the change toward inclusion. It wanted to emphasize that while many of its students are of Mexican descent (Chicano/Chicana), it also embraces those who trace their heritage to other Latin American countries (Latino/Latina).

So, what about the "x" in Latinx and Chicanx? As it turns out, there's a lot riding on that one little letter.

Swapping out "x" for the final "o" or "a" (which in Spanish signify masculine and feminine forms, respectively) renders these terms gender neutral. "Students wanted us to recognize communities that do not fall within the gender binary of masculinity or femininity," says Billy Vela, La CASA's director.

The term Latinx has gained popularity on the U.S. stage in the last four years, according to Google Trends data. The x is showing up elsewhere, too. You may have noticed that newspapers like The New York Times use "Mx." as a substitute for "Mr." and "Mrs." in stories about transgender people. The pronoun "they" is often used as a gender-neutral swap for "he" or "she," as well.

While many applaud these variations as ways to address gender biases baked into language, others lament what they see as a chipping away of right and wrong in speech. But as it turns out, bending—and occasionally breaking—traditional rules of communication has a long precedent. The evolution of language, some argue, may signal that our society is alive, well and thriving.

So why is it that we get so upset when language changes? And why can't it ever seem to just stay put?

Criticism aimed at the word Latinx includes charges of linguistic imperialism, because the word is pronounceable in English but not in Spanish. Some call it elitist for trying to erase traditional gender roles and history.

But according to Andrew Simpson, chair of the Department of Linguistics in the USC Dornsife College of Letters, Arts and Sciences, this evolution of words is nothing new. Nor is the fierce backlash.

"At various points in time, different bodies have tried to standardize languages and 'fix' them," Simpson says. He's referring to entities like la Real Academia Española and l'Académie française, which seek to protect Spanish and French, respectively. But languages have evolved anyway, he says. "It's inevitable that language is going to continue to change, and you can't stop it."

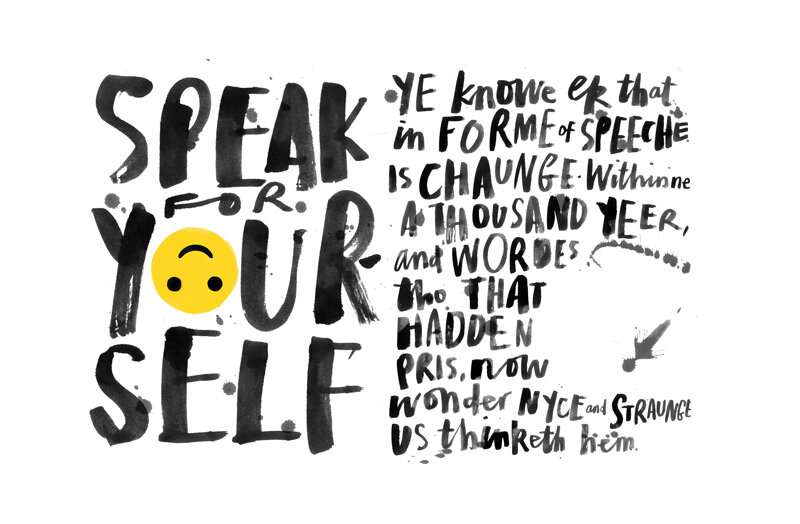

As Simpson details in his book "Language and Society: An Introduction," linguists see the process of language change through two different lenses: historical and sociolinguistic. Historical changes are those that happen over long periods of time. For example, the English we use today is dramatically—and grammatically—different from Old English and Middle English.

If you've ever tried to read, say, Beowulf or The Canterbury Tales, you know that these earlier iterations of the language seem almost like foreign tongues. Over the course of centuries, "English lost its case system and changed its word-order patterns," Simpson explains, likely due to early English speakers' interactions with groups such as Vikings and Germanic Anglo-Saxons.

On the other hand, sociolinguistic changes are incremental tweaks that happen from year to year as new words, meanings and pronunciations gain traction. And if you've ever been exasperated by a teenager saying "like" every other word, you already know that such changes often surface first among the younger generation. "Young people initiate change, particularly in high school," Simpson says. "You're moving away from your family. You're forming a new tribe. And you need a new language for your tribe."

Adolescence is also a period of trying on various identities as a means of self-expression. "Young people may feel a need to distinguish themselves," Simpson says. Language, just like fashion and music taste, is another means to do so.

Simpson points to the fairly new phenomenon of vocal fry (a style in which speakers end sentences in a low-pitched, creaky voice) as an example of how young people align themselves with desirable identities. Popularized by pop-culture figures like Britney Spears and Kim Kardashian, vocal fry has been adopted mostly by female speakers to communicate the image of a successful, "California-cool" woman.

Yet the maelstrom of negative reactions to vocal fry reveals how such twists in the use of language can feel particularly alienating to an older generation. "You get used to a system of words and word patterns that's established, and then younger-generation speakers come along and change that, so it seems like a threat to what you're used to," Simpson says. "Any kind of threat to an established order is something you might react to."

When older generations see younger people turning away from traditional norms, Simpson says, their reaction may be, "Our society is breaking down." That resistance to language change demonstrates the close relationship between language and power that exists across cultures. "Most societies have a power structure," Simpson says. "There's a pressure to reflect that in the language." When marginalized groups modify language conventions to assert equality—as in the case of Latinx or gender-neutral pronouns—it's not surprising that some people get upset.

History is rife with examples of how language becomes a battleground during social shakeups. Margaret Rosenthal, chair of the Department of French and Italian at USC Dornsife, studies female writers in early modern Italy, where anxieties about gender norms ran high.

In the 15th century, the rise of the printing press allowed for publication and distribution of books beyond the male elite, she says. "Women had more access to learning, and more women were writing and reading than ever before," Rosenthal says. Yet, "women were still very much the property of their husbands. Generally speaking, there was a lot of fear related to what would happen with all of that knowledge."

Sixteenth-century male poets turned to vulgar language—"misogynist, filthy, obscene poetry," Rosenthal says—to publicly denounce female writers and condemn their entry into a sphere previously reserved only for men. Rosenthal, whose book The Honest Courtesan about the writer and courtesan Veronica Franco was adapted into the 1998 film Dangerous Beauty, has found many instances where female poets responded to these attacks through writing.

One example is the poet Vittoria Colonna, who was a close friend of the artist Michelangelo. In some of her poems, she used a typically male qualifier to speak about herself. The pointed wording shows that she viewed her gender and her strength as not solely limited to a binary system, Rosenthal says.

Additionally, Colonna flips the gender of "pronouns, nouns, and adjectives to talk about the ways she conceives of herself as not wholly—according to society's views—feminine or masculine, but as a blurring and slippage between them." By playing with the gendering of certain words, poets like Colonna could make a point about female power and the ambiguity of gender identity.

Much like the printing press did during the Renaissance, smartphones and social media are upending the ways we communicate and share knowledge today. And that has important implications for the spread of new words and speech patterns, since language travels at warp speed in cyberspace.

In his book Language and Society, Simpson discusses how language variations typically catch on by being passed through several channels: interpersonal relationships, geographical ties and mass media. But the internet is transforming all of these factors. Social networks have gone digital. Remote connections create shortcuts around geographical barriers, and users can now bypass traditional media gatekeepers—such as TV networks and book publishers—to create content that might be seen by millions.

Given that young people's expressions of personal and group identity are a major driver of language change, it's worth noting that this is the first generation in history that holds the power of mass media literally in its hands. The smartphone gives youth access to the same digital platforms as adults and affords them the ability to disseminate content previously reserved for media companies, allowing them to spread new ideas more quickly and widely than ever before, says Alison Trope MA '94, Ph.D. '99, a professor in the USC Annenberg School for Communication and Journalism. Depending on your perspective, the impact that smartphones—and the influencers who wield them—are having on the dissemination of language may seem either Gucci or wack (translation: good or bad).

On the positive side, digital platforms allow for a greater diversity of voices to be heard—more than are typically represented in traditional media. Marginalized groups may increasingly define their identity on their own terms. Trope, founder of Critical Media Project, a free online media literacy resource for educators and youth to explore identity politics, says that posting thoughtful content on platforms like Instagram and YouTube can be powerful.

It enables youth of color, LGBTQ people and others to challenge stereotyped representations "through their own narratives, their own voice, their own kind of counter-storytelling." Such portrayals can push society toward more-inclusive language. Sharing new vocabularies of identity can go viral: Just think back to Latinx, which got a boost toward the mainstream lexicon through sites like Tumblr and Twitter.

But on the negative side, some may fear that youthful textspeak is poised to topple artful, subtle and meaningful language as we know it. With all of the LOLing and OMGing going on, digital messaging has been demonized as ushering in the demise of grammar, punctuation and the integrity of structured written expression.

Some lament that the visual language of emoji may at some point replace traditional words entirely and return us to an age of pictographs. Simpson notes that, so far, there's no hard evidence of what one language expert dubbed "linguistic Armageddon."

But there's no doubt that visual accoutrements like emoji and gifs could potentially cause trouble by adding another layer of complexity to language. Conveying your intended meaning "is hard enough when you're texting," Trope says. "We have a lot of crossed wires because everything is shorthand. Communicating like that can have unintended consequences, revealing implicit biases and problematic cultural appropriation."

It may be tempting to view the unique complications of the digital age as signs that language is simply on its way down the drain. But Simpson cautions against such a judgment. From a linguistics perspective, any evolution in a language is just part of its natural life cycle as it adapts to social shifts. "I think what every linguist would say is that it's neither progress nor decay. It just happens.

"So, get used to it," he says with a smile.

Provided by University of Southern California