This article has been reviewed according to Science X's editorial process and policies. Editors have highlighted the following attributes while ensuring the content's credibility:

fact-checked

peer-reviewed publication

trusted source

proofread

Starlings' migratory behavior found to be inherited, not learned

Young, naïve starlings are looking for their wintering grounds independently of experienced conspecifics. Starlings are highly social birds throughout the year, but this does not mean that they copy the migration route from each other.

By revisiting a classic "displacement" experiment and by adding new data, a team of researchers at the Netherlands Institute of Ecology (NIOO-KNAW) and the Swiss Ornithological Institute (Vogelwarte Sempach) have settled a long-standing debate. Their findings are now published in the journal Biology Letters.

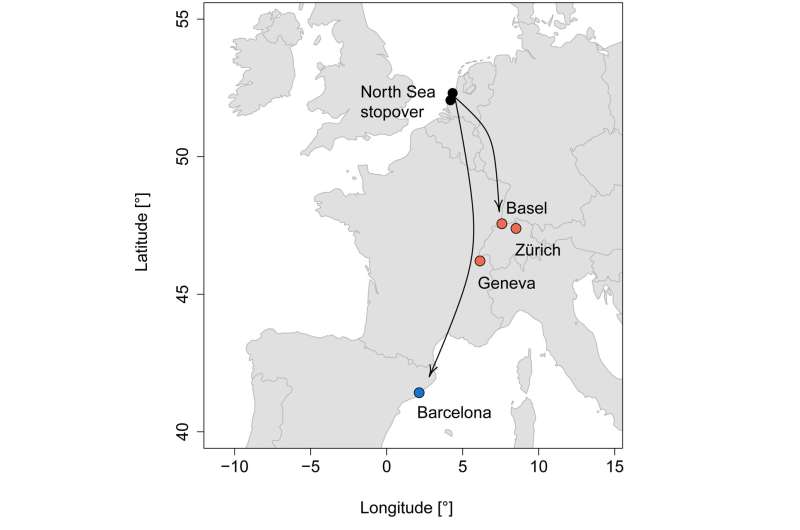

The question of how migratory birds locate their migration routes has intrigued mankind for centuries. Biologist Albert Perdeck from the Netherlands aimed to find answers when he displaced thousands of migrating starlings by plane from the Netherlands to Switzerland and Spain in the 1950s and 1960s.

This experiment has become a classic study on the migratory orientation of birds. Now, 70 years later, colleagues have confirmed his findings and were able to solve a long-lasting scientific debate using this historical dataset.

The birds were individually recognizable using light-weight metal leg rings with a unique code—a method used by the Dutch Center for Avian Migration and Demography, Vogelwarte Sempach and European partners until this day. Ring recoveries indicated that relocated young and adult starlings used different strategies to reach the winter destinations in the British Isles and France.

"Adult starlings were aware of this move and adjusted their migratory orientation to reach their normal wintering areas," according to Morrison Pot at the NIOO-KNAW. "Young starlings continued in a south-westerly direction—the direction they would have chosen when departing from the Netherlands—and reached 'wrong' destinations in southern France and Spain."

Over the years, experts in the field of avian migration have been divided about the interpretation of Perdeck's results. Pot states, "Starlings are highly social animals and, according to some experts, the relocated young starlings may just as well have joined a flock of local conspecifics."

The relocated starlings would have copied the migratory behavior of their new friends showing them where to go. "If true, the migratory route is largely learned instead of inherited"—a major difference.

The team of researchers retrieved the historical data of Perdeck's displacement experiments in the paper archives of the Dutch Center for Avian Migration and Demography and compared the migratory orientation with the migratory behavior of local Swiss and Spanish starlings. "The latter data were retrieved from institutional archives, but were unavailable in Perdeck's days."

By re-analyzing this historical dataset, the team showed that the migratory orientation of the relocated starlings differed from the local conspecifics. Starlings are thus no social migrants or "copycats." The alternative social explanation of Perdeck's results has thus been debunked. As explained by Pot, "Starlings travel independently and decisions about where to go are not overruled by the migratory behavior of others."

Recently, a study in collaboration with Vogelwarte Sempach showed that starlings migrate at night. This is in line with the 70-year-old findings, because how would you follow someone in the pitch darkness of the night?

Learned or inherited behavior, why does it matter? "In times of rapid changes in global climate and land-use, it is of great importance to understand whether migratory behavior is largely inherited or learned," says lead scientist and head of the Dutch Center for Avian Migration and Demography Henk van der Jeugd.

Inherited behaviors are less flexible to rapid change. "Although starlings are numerous and widespread birds that have adjusted to human dominated landscapes, their migratory behavior is likely less flexible."

More information: Morrison T. Pot et al, Revisiting Perdeck's massive avian migration experiments debunks alternative social interpretations, Biology Letters (2024). DOI: 10.1098/rsbl.2024.0217

Journal information: Biology Letters

Provided by Netherlands Institute of Ecology