How a male-hating bacterium rejuvenates

A team from Immanuel Kant Baltic Federal University together with their Russian colleagues carried out genetic analysis of the symbiotic bacterium Wolbachia that prevents the birth and development of males in different species of arthropods. It turns out that the microorganisms exchange their genes to rejuvenate. The results of the study were published in the Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution journal.

Different species may have different relationships with each other: Some compete for limited resources, and some feed off their hosts. Nevertheless, if two species cohabitate in some way, it is called symbiosis, and its participants are symbionts. Some symbionts can be inherited.

The Wolbachia bacterium is the most widespread symbiont in the biosphere. Many arthropods and some nematode worms have it. The bacterium lives in the reproductive tissues and is inherited from mother to progeny via the oocytes of infected females. Scientists believe that currently these bacteria are being transformed into a new cell organelle.

Wolbachia manipulates the reproductive process of its host. For example, it may "forbid" infected males to inseminate healthy females to prevent them from producing offspring. All embryos die at early stages of development, and scientists are still unable to understand how the bacteria manage to do it. In other species the bacterium increases the share of females in the population to spread the infection. To do so, it feminizes genetic males or causes thelytokous parthenogenesis—a process in which female progeny are produced without insemination. However, sometimes Wolbachia can be very useful for its host—it synthesizes vitamins and suppresses harmful mutations and even some viruses.

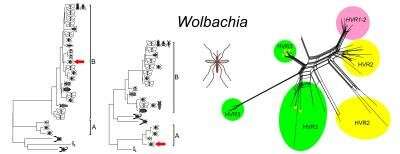

According to the scientists, these bacteria can be very different from the genetic point of view in one host species and very similar in different ones. It indicates that the bacterium has several individual symbiotic relations. So, there are several supergroups—phyletic lines of Wolbachia.

Although the bacterium was discovered in 1924, a lot is still unknown about it, including the beginning of its symbiosis with arthropods and the mechanism of its transmission from one species to another. Moreover, how it controls the reproductive system of its host is also unclear.

Previously the authors of the work analyzed phylogenetic relations between different Wolbachia strains and discovered many contradictions in its evolutionary history. They are associated with large-scale horizontal gene transfer—a process in which an organism transfers its genetic material to another organism that is not its progeny. For example, many centuries ago, plants allowed photosynthesizing cyanobacteria to live in their cells. With time, they turned into chloroplasts and transferred genes to their hosts' genomes.

To identify the phylogenetic relations, the authors used a special approach—they classified different Wolbachia bacteria by alleles (variations) of each gene and looked for irregular accumulation of nucleotide substitutions. In the course of this work, the authors studied Wolbachia in mosquitoes using the same method, i.e. by comparing their alleles to the alleles of the same bacteria in other species. They had to understand where the mosquitos got the symbiont from.

"We analyzed genetic profiles of different Wolbachia supergroups and concluded that the bacteria in mosquitoes are very similar to those found in lepidopteras, and in one case, also in ants. We don't know yet why it happened. However, we assume the bacteria may be transferred by the ticks that live on the bodies of these insects," said Yury Ilinsky, a co-author of the work, Ph.D. in biology, and a specialist of Immanuel Kant Baltic Federal University.

The scientists found that different Wolbachia bacteria exchange genetic information. They can rejuvenate, and therefore mend their broken genes. The exchange usually takes place among the bacteria of the same supergroup, but sometimes, remote bacteria are involved, as well. It means that the bacterium changes hosts more often than the scientists believed, and also that it's older than previously estimated.

"Our global goal is to understand the pattern of genetic distribution of Wolbachia in arthropods. After that, we would like to understand how and at what rate it changes hosts," concluded Yury Ilinsky.

More information: Elena Shaikevich et al, Wolbachia symbionts in mosquitoes: Intra- and intersupergroup recombinations, horizontal transmission and evolution, Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution (2019). DOI: 10.1016/j.ympev.2019.01.020

Journal information: Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution

Provided by Immanuel Kant Baltic Federal University