Tumultuous galaxy mergers better at switching on black holes

A new study by researchers at the University of Colorado Boulder finds that violent crashes may be more effective at activating black holes than more peaceful mergers.

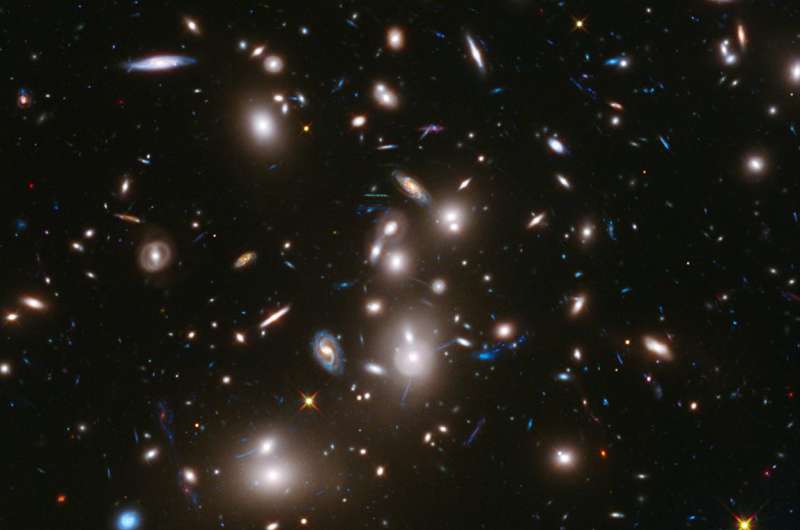

When two galaxies collide, the supermassive black holes that sit at their centers also smash together. But before they do, these galaxies often flicker on, absorbing huge quantities of gas and dust and producing a bright display called an Active Galactic Nucleus (AGN).

But not all mergers are created equal. In some such marriages, only one black hole becomes active, while in others, both do.

The research team led by CU Boulder's Scott Barrows discovered that single activations seem to occur more often in mergers in which the galaxies are mismatched—or when one galaxy is huge and the other puny.

When lopsided galaxies join, "the merger is less violent, and that leads to less gas and dust falling onto the black holes," said Barrows, a postdoctoral research associate in the Center for Astrophysics and Space Astronomy (CASA). "And the less material you have falling onto the black holes, the less likely you are to have two of them become AGNs."

The researchers presented their findings today at a press briefing at the 232nd meeting of the American Astronomical Society, which runs from June 3-7 in Denver, Colorado.

Barrows and his colleagues used data collected by the Chandra X-ray Observatory to systematically scan the night sky for the signatures of AGNs. They spotted mergers in progress by looking for "offset galaxies," or galaxies with a single AGN that sits away from the center of the galaxy. Such a lack of symmetry suggests that a second supermassive black hole, which hasn't been turned on, might be hiding nearby.

Barrows and his colleagues next assembled a sample of 10 offset galaxies and compared that sample to galaxies with a pair of AGNs.

The results were stark: Nine out of the 10 galaxies with only one active black hole came from lopsided mergers, or cases in which one galaxy was more than four times the size of the other. Two-thirds of the galaxies with two active black holes, in contrast, were experiencing clashes among near equals.

Barrows explained that when galaxies of roughly equal size meet, their black holes exert tremendous gravitational forces on each other. Those forces, in turn, send clouds of gas and dust raining onto the black holes.

"It's these torques that extract energy from the gas and dust, allowing it to fall into the nucleus of the black hole," Barrows said. In mismatched mergers, "you simply have smaller forces exerted on the gas and dust in each galaxy."

The team didn't find any rhyme or reason to which black hole activated during a mismatched merger. In some cases, Barrows said, it was the bigger black hole. In other cases, the smaller one. Next up, he and his colleagues will focus on how the smashing together of two black holes affects the galaxies themselves, including how they create and destroy stars.

Provided by University of Colorado at Boulder