Circumbinary castaways: Short-period binary systems can eject orbiting worlds

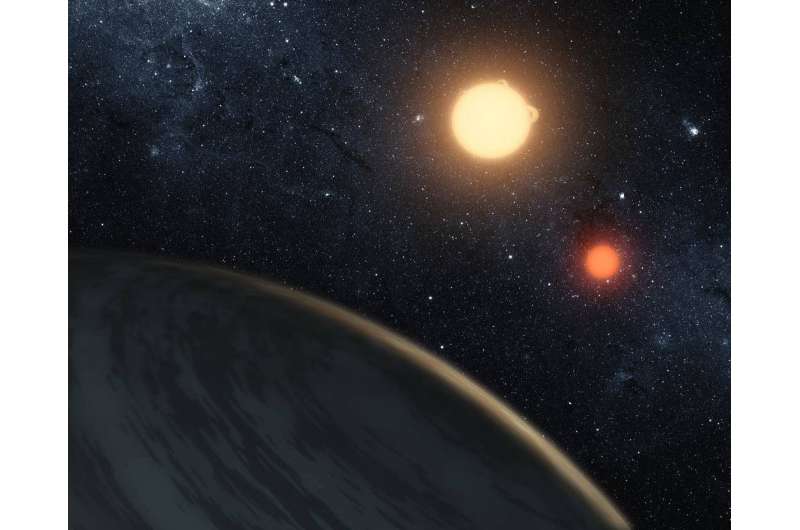

Planets orbiting "short-period" binary stars, or stars locked in close orbital embrace, can be ejected off into space as a consequence of their host stars' evolution, according to new research from the University of Washington.

The findings help explain why astronomers have detected few circumbinary planets—which orbit stars that in turn orbit each other—despite observing thousands of short-term binary stars, or ones with orbital periods of 10 days or less.

It also means that such binary star systems are a poor place to aim coming ground- and space-based telescopes to look for habitable planets and life beyond Earth.

There are several different types of binary stars, such as visual and spectroscopic binaries, named for the ways astronomers are able to observe them. In a paper accepted for publication in Astrophysical Journal, lead author David Fleming, a UW astronomy doctoral student, studies eclipsing binaries, or those where the orbital plane is so near the line of sight, both stars are seen to cross in front of each other. Fleming will present the paper at the Division on Dynamical Astronomy conference April 15-19.

When eclipsing binaries orbit each other closely, within about 10 days or less, Fleming and co-authors wondered, do tides—the gravitational forces each exerts on the other—have "dynamical consequences" to the star system?

"That's actually what we found" using computer simulations, Fleming said. "Tidal forces transport angular momentum from the stellar rotations to the orbits. They slow down the stellar rotations, expanding the orbital period."

This transfer of angular momentum causes the orbits not only to enlarge but also to circularize, morphing from being eccentric, or football-shaped, to perfect circles. And over very long time scales, the spins of the two stars also become synchronized, as the moon is with the Earth, with each forever showing the same face to the other.

The expanding stellar orbit "engulfs planets that were originally safe, and then they are no longer safe—and they get thrown out of the system," said Rory Barnes, UW assistant professor of astronomy and a co-author on the paper. And the ejection of one planet in this way can perturb the orbits of other orbiting worlds in a sort of cascading effect, ultimately sending them out of the system as well.

Making things even more difficult for circumbinary planets is what astronomers call a "region of instability" created by the competing gravitational pulls of the two stars. "There's a region that you just can't cross—if you go in there, you get ejected from the system," Fleming said. "We've confirmed this in simulations, and many others have studied the region as well."

This is called the "dynamical stability limit." It moves outward as the stellar orbit increases, enveloping planets and making their orbits unstable, and ultimately tossing them from the system.

Another intriguing characteristic of such binary systems, detected by others over the years, Fleming said, is that planets tend to orbit just outside this stability limit, to "pile up" there. How planets get to the region is not fully known; they may form there, or they may migrate inward from further out in the system.

Applying their model to known short-period binary star systems, Fleming and co-authors found that this stellar-tidal evolution of binary stars removes at least one planet in 87 percent of multiplanet circumbinary systems, and often more. And even this is likely a conservative estimate; Barnes said the number may be as high as 99 percent.

The researchers have dubbed the process the Stellar Tidal Evolution Ejection of Planets, or STEEP. Future detections—"or non-detections"—of circumbinary around short-period binary stars, the authors write, will "will provide the best indirect observational test of the STEEP process.

The shortest-period binary star system around which a circumbinary planet has been discovered was Kepler 47, with a period of about 7.45 days. The co-authors suggest that future studies looking to find and study possibly habitable planets around short-term binary stars should focus on those with longer orbital periods than about 7.5 days.

Fleming and Barnes' co-authors are UW astronomy professor Tom Quinn, post-doctoral researcher Rodrigo Luger and undergraduate student David E. Graham. This work used storage and networking infrastructure provided by the Hyak supercomputer system at the UW, funded by the UW's Student Technology Fee.

As for habitability and the search for life, Fleming said planets orbiting short-term eclipsing binaries might otherwise be attractive targets for closer study, with their edge-on angle showing eclipses, and more, to the distant viewer.

"But this mechanism tends to kill them," he added. "So, it's not a good place to look."

More information: On The Lack of Circumbinary Planets Orbiting Isolated Binary Stars, arXiv:1804.03676 [astro-ph.SR] arxiv.org/abs/1804.03676

Journal information: Astrophysical Journal

Provided by University of Washington