Turning the evolutionary clock back on a light-sensitive protein

We are inching closer to using light to help cure diseases. The key is harnessing the power of proteins that are sensitive to light.

The Kerfeld lab studies the orange carotenoid protein (OCP), unique to cyanobacteria (previously known as blue-green algae), which are organisms that are prodigiously productive at photosynthesis.

The OCP and its homologs, protect cyanobacteria when they are exposed to too much sunlight, which would otherwise damage the photosynthetic systems, and if extreme, damages the cell itself.

And just as shining light triggers the OCPs activity, scientists want to use that response to activate engineered, custom health technologies.

But first, we need to understand how OCP and its relatives work, according to Sigal Lechno-Yossef, a post-doc in the Kerfeld lab.

In her latest study, published in The Plant Journal, Sigal shows how the two parts of the OCP interact when split apart. She also manages to create new, synthetic OCPs by mixing and matching the building blocks from different types of the OCP found in nature.

Reversing evolution

In nature, proteins are made up from a limited number of domains – think of them as Lego blocks – that combine in different ways.

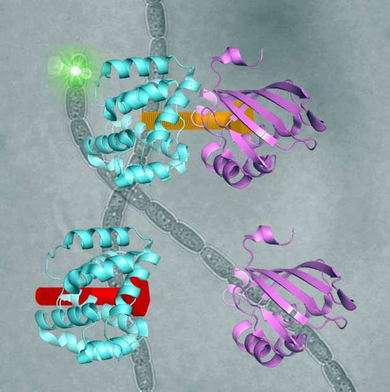

The OCP is made out of two blocks, called C-terminal domain and N-terminal domain, spanned by a carotenoid pigment that bolts the two parts together.

This is how they work:

Sigal reversed this evolutionary event in the lab – call it devolution. "We wanted to better understand the evolution process of the OCP from domain homologs found in cyanobacteria today," Sigal says.

The scientists broke down the connecting carotenoid bond to split apart an OCP protein. Then, they put both domains into a test host to see if they would find each other and connect again – basically retracing what they think was the evolutionary process.

"Without carotenoid, the two parts stayed separate. Once we put in the carotenoid, they latched onto each other. We basically created multiple synthetic versions of the OCP."

The synthetic OCP reactions were similar to their natural cousins' in the presence of light. But for some reason, probably in the fine details of their structures, only one of the synthetic versions came back together in the dark.

As a bonus, even though the two OCP domains remained separate without the carotenoid bolt, that configuration yielded some interesting insights.

"In the OCP, the N-terminal domain binds to the carotenoid more strongly," Sigal says. "When we isolated the domains, we found that, the C-terminal domain, when on its own, can bind to the carotenoid."

Proteins similar to the C-terminal domain are widespread in plants, bacteria, and some animals, which opens new possibilities to explore engineering applications in a range of organisms, beyond bacteria.

Using light in synthetic biology

Cheryl Kerfeld, principal investigator at the Kerfeld lab, thinks that precise knowledge of the structures of the various OCP building blocks makes them especially amenable to engineering.

The long-term goal is to use the OCP and its separate subcomponents in new, synthetic systems, specifically optogenics, a recently developed technique that uses light to control processes in living cells.

Optogenetics, highlighted in a 2010 Science article on Breakthroughs of the Decade," is showing us how the brain works, how we learn, or how we wake up. Scientists hope that targeting specific brain cells will help us cure Parkinson's or Alzheimer's, even combat mental illnesses.

Light-sensitive proteins, similar to the OCP, are key to activating and controlling events in optogenetic applications. Although OCP has yet to be tried in a specific optogenetic application, the Kerfeld Lab thinks their properties make them likely to be useful.

"OCPs respond faster to light, compared to the current light-sensitive proteins used in optogenetic experiments," Sigal says. "They are also so flexible in how they break apart and come back together. They are a great candidate."

She adds, "Now that we've shown we can make artificial hybrid OCPs, we have a wider range of options." For example, if a patient requires multiple doses of medicine, their intake could be controlled with a synthetic OCP that assembles and disassembles to control dosages.

Or, OCP domains could be used separately, for example, as a kill switch for treatments that require single doses, as opposed to multiple cycles.

"We are still in the theoretical phase of imagining applications, but we are not far from where we can start experimenting with synthetic systems."

More information: Sigal Lechno-Yossef et al. Synthetic OCP heterodimers are photoactive and recapitulate the fusion of two primitive carotenoproteins in the evolution of cyanobacterial photoprotection, The Plant Journal (2017). DOI: 10.1111/tpj.13593

Journal information: The Plant Journal

Provided by Michigan State University