Scientists are reconstructing the relationship between modern humans and Neanderthals

The Neanderthals and modern humans must have co-existed in Europe for several thousand years. What happened when they encountered each other and how they influenced one another are riveting questions. Jean-Jacques Hublin and his team at the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology in Leipzig are searching for answers to them. In the process, they have found clues as to what the Neanderthals learned from Homo sapiens—and what they didn't.

Nobody knows what the baby died of. An infection? Attacked by a wild animal? A congenital disease? Perhaps. In any case, the parents left the child behind in a cave in central France, which prehistorians today call the Grotte du Renne. It's even possible that the parents buried their baby in mourning.

Time travel: At the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology in Leipzig, the Human Evolution Department headed by Jean-Jacques Hublin conducts research into human prehistory, paleoanthropology. Postdoc Frido Welker prepares bone fragments, some of them splinters, from the Grotte du Renne. Such fragments had previously seemed to be of no use to experts. Or to put it more accurately, paleoanthropologists such as Welker had no procedures for extracting insights from such damaged witnesses of prehistory.

Thanks to so-called paleoproteomics, this has now changed. This method can detect even the minutest traces of proteins in ancient bone material and reveal information about the identity of the living being from which it stems—a 'pretty revolutionary method,' as Jean-Jacques Hublin says. Proteins survive ten times longer than DNA in ancient bone material. Examination of the genome was previously regarded as the standard method of assigning a bone to a certain animal. Paleoproteomics could take over this mantle from DNA analysis. 'The proteins of Stone Age bones contain valuable information on the phylogenesis and lifestyle of these people,' Welker explains.

It transpired the baby from the Grotte du Renne was a little Neanderthal girl, not even weaned, perhaps six months to two years old on the day she died 44,000 to 40,000 years ago. Her meager remains shed more light than ever before on a dispute in the paleoanthropological world of experts that has been going on for decades. This genre of research is marked in some cases by heated debate. For example, on the question of how Neanderthals and 'modern humans'—meaning you and me—encountered each other in Europe roughly 45,000 years ago. 'There was a cultural transfer between the two hominids,' states Jean-Jacques Hublin with conviction, following the latest high-tech examinations carried out by his team. 'It was only when Homo sapiens arrived that the Neanderthals suddenly began to do things they had never done before.'

The Leipzig-based scientist assumes that 'there was no need of any particularly intensive contact' for this exchange. Let alone any love affair between Homo sapiens and Homo neanderthalensis, as was widely propagated in past years. 'There are too many stories invented,' says the Frenchman. 'It's highly likely that the truth was anything but romantic.'

The witnesses to this past dating back millennia to millions of years—bones, teeth and cultural objects such as tools or jewellery—are limited. They often lead to acrimonious discussions. 'Of course I find that irritating', Hublin says, 'We would be well advised to distinguish between fact and fiction.'

The world was almost devoid of humans in the Stone Age

Let us look at the subject of Homo sapiens and Neanderthals, therefore, in this light, one of the Max Planck scientist's specialist areas. Ever since the first bones of this hominid were discovered in the Neander Valley near Düsseldorf in 1856, legends have been woven around his existence. Primarily because he looks so different from modern humans.

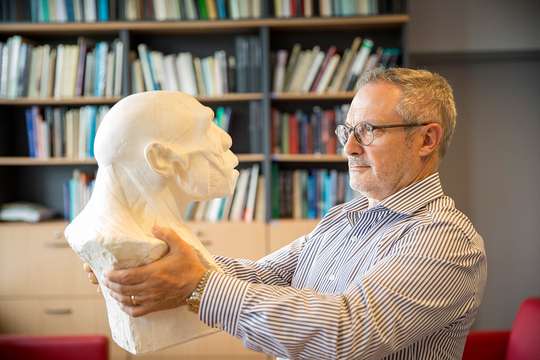

Standing at no more than 1.70 meters, they were not particularly tall; but their physique was strong and powerful with a very prominent chest, the males weighing up to 90 kilos. 'Very impressive,' says Jean-Jacques Hublin as he gazes at the sculpture of a Neanderthal head in his office. It was fashioned at the beginning of the 20th century but is still essentially in line with current knowledge. This means that the face is large and elongated with striking ridges over the eyebrows while the nose is voluminous, the jaw massive and the chin somewhat receding. 'Were you to meet a Neanderthal in the train,' the paleoanthropologist explains, 'you would change compartments.'

Even 45,000 years ago, it must have been a highly unusual event when members of modern man Homo sapiens first came across members of Homo neanderthalensis in the forests and meadows of Europe. 'For both sides,' Hublin says laughing. According to the results of recent studies, the Neanderthals could already look back on at least 400,000 years on the continent—in an area ranging from Spain to the Russian Altai Mountains and up to the latitudes of North Germany.

As hunters and gatherers, they probably wandered in groups numbering no more than 50 to 60 men and women across stretches of land measuring many thousands of square kilometers. They were able to kill even large animals such as bison and horses with great efficiency. They also consumed plants and vegetables to a much larger extent than previously believed. And Neanderthals probably lived at a faster rate. Hublin's team determined the age of a Neanderthal child from wafer-thin layers of enamel on its teeth. It emerged that the children of this hominid matured one to two years earlier than the offspring of modern humans.

Their winters were brutal and long. It's likely that many of their small groups simply died out in long phases of starvation and were replaced by new members. Even in times of their widest distribution, there were probably no more than an estimated 10,000 'Neanderthal Europeans'. 'The Stone Age was an empty world,' Hublin says. According to the latest studies, Neanderthals faced this lonely existence with mental faculties that were almost as sophisticated as those of their cousin and (future) adversary. 'They were more complex than we had long assumed,' the researcher concedes. And furthermore: 'Both hominids were almost identical at this time in terms of their cognitive powers, definitely not ape-like but also not like us.'

Homo sapiens brought with him a superior mind

From a technical standpoint, the Neanderthals were definitely skilled, as evidenced by the intricate spears they made even in their early days. They even developed a tool culture roughly 120,000 years ago—or 'industry' as paleoanthropologists say—which characterized a whole epoch: the Mousterian. During this period, they produced tools like arrow points, scrapers, scratchers and blades which were hewn from stones in a characteristic fashion. Explorers have found artifacts from this culture in many archaeological sites—for example, in the before-mentioned Grotte du Renne in Burgundy.

The Neanderthals thus coped very well with the adverse conditions in Europe. They would doubtless have survived for further tens of thousands of years if another species had not suddenly created a stir in Europe 45,000 years ago: modern humans. The new arrivals were much more delicately built than the established species. But the main thing was that they brought with them a mind that was ultimately superior. Homo sapiens not only worked stones but also fashioned fishhooks from fish bones, made jewellery from bones, snails and egg-shells, and formed points for arrows and harpoons. No sooner had they arrived in Europe than they created their very own industry—this period is referred to as the Aurignacian. It is typified by projectile points made from ivory and bones, which at the time were top in hunting technology.

The oldest bones bearing testimony to modern humans are to be found in North Italy, and soon they were scouring areas east of the Rhine in Baden-Württemberg, not far from the Grotte du Renne. The roof of this cave collapsed around 20,000 years ago burying everything beneath it. A stroke of luck for archaeologists who have been uncovering rich finds from the various layers of the buried cave for decades. The cave was clearly a popular place of refuge during the Stone Age. People were continually stopping by. Besides the Mousterian artifacts in the deeper, older excavation layers, archaeologists also hit upon remains of the Aurignacian industry in the upper, more recent layers.

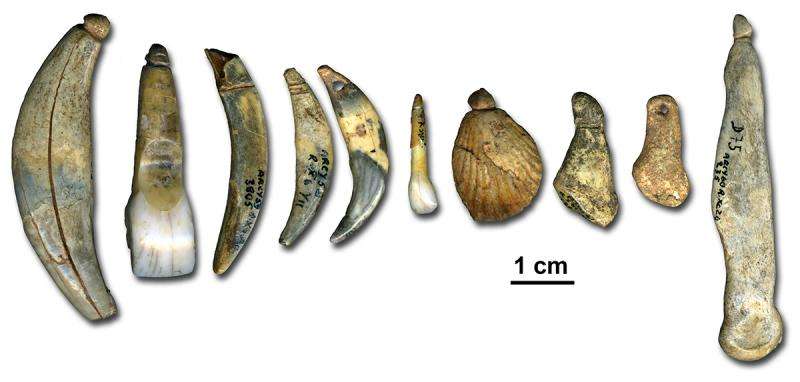

In an intermediate layer, relics of the Châtelperronian (CP) culture were found in the Grotte du Renne—and at further sites with deposits. Many rings, pendants and clasps of ivory, antlers and other materials were found in the 1950s. Earrings, perforated, grooved teeth used as decorative pendants, fossils, and so on. Points or knives with a rounded, blunted back are also very typical. These elaborately worked utensils are sometimes strongly reminiscent of the following Aurignacian industry of Homo sapiens. And not of the Neanderthals.

At the same time, however, easily identifiable remains of bones and teeth were found in the CP layer of the Grotte du Renne—from Neanderthals, as a study from the 1990s suggested. However, this sparked renewed debate. In 2010, British researchers believed they had proved that there were age differences between the various finds from the Châtelperronian layer. They interpreted their findings to mean that the jewellery had been made by modern man and only subsequently mixed up with the Neanderthal relics when the lower layers were disturbed.

Jean-Jacques Hublin was disinclined to believe this, and together with international partners he embarked on a series of tests lasting several years. First, his team selected 40 well-preserved bone samples from the Grotte du Renne—mostly from areas containing the CP jewellery or Neanderthal remains, and less frequently from Mousterian or Aurignacian layers. In addition, the researchers examined the shin-bone of a Neanderthal from a different, well-known French excavation site in Saint-Césaire.

The scientists extracted collagen from the bone samples, an organic component of the connective tissue, consisting of protein chains. Then came the hour of modern analytical equipment. 'I am obsessed with technology,' Hublin says, smiling. For example, there are half a dozen of the latest mass spectrometers in his department—on the one hand, high-tech scales that measure the mass of atoms and molecules, and on the other, accelerator mass spectrometers that can determine the exact age of bones, for example, by using the decay of various hydrogen isotopes in molecules.

Neanderthals adopted many innovations

The extensive analyses showed that the samples from the Châtelperronian layers are between 41,000 and 35,500 years old and therefore must indeed be assigned to this culture. In addition, the ages of the Châtelperronian finds overlapped with the finds from other layers—which rules out any mixing of the sediments. With an age of 41,500 years, the Neanderthal skeleton from Saint-Césaire also fits into the picture excellently.

The Neanderthals could thus also have created the CP industries in France. Could have. But there was still a lack of unambiguous evidence that the bones from the CP layer in the Grotte du Renne once belonged to Neanderthals—and not to modern humans.

The team working with Hublin therefore applied completely new methods for the first time in its study: Peptide Mass Fingerprinting and Shotgun Proteomics, two special methods of proteomics. This method can be used to determine whether collagen comes from the bone of a Neanderthal or that of a modern human. Tiny bone samples suffice for the test, and this is the aspect that is crucial and new. And it is also the precise reason why the scientists were able, for the first time, to conduct a molecular analysis of 28 bone fragments from a layer of sediment assigned to the Châtelperronian period.

'They come from Neanderthals,' says Frido Welker. By combining the tests with other proteomic methods—for instance the analysis of the sequence of amino acids of a protein—and paleogenetics, it was ultimately clear that the bone fragments were those of an infant from the Châtelperronian period. 'Our study shows that with paleoproteomics alone, it is possible to differentiate between different Early Stone Age groups within our Homo genus,' according to Welker.

The big question overshadowing the studies: How did Homo sapiens get on with Homo neanderthalensis? The new finds can be interpreted in different ways. One could interpret them to mean that the Neanderthals made an unexpected leap forward in their development of their own accord just as Homo sapiens spread across Europe. 'However, that would border on a miracle,' Jean-Jacques Hublin reasons. For him, it is far more likely 'that the two hominids came into contact and the Neanderthals adopted some of the innovations of modern man.'

The Neanderthals could have conceivably found tools and jewellery made by Homo sapiens—and then copied them and introduced them to neighbouring groups when the occasion arose. They were intelligent enough to do so. Perhaps a well-meaning, modern human showed them how to make these wonderful articles. Maybe there were barter transactions between the groups. Who knows? We are back in the realm of ever-popular legends. And Jean-Jacques Hublin again urges caution.

Two percent of our DNA comes from the Neanderthals

There was no need of constant contact for the transfer of cultural innovations and certainly not of any close friendship. Modern humans, too, had to master the harsh life of a hunter and gatherer and was in competition with his contemporaries in the other species for territory and food. Even if there were only dozens or a few hundred groups that seldom encountered each other in the empty world of the Stone Age, most meetings of these contemporaries are more likely to have been unfriendly if not hostile, aggressive and violent.

Admittedly, there is no concrete proof that this was the case. Nevertheless, we know that encounters between competing tribes seldom went smoothly in human history. It is highly likely, therefore, that things would have been no different when Homo sapiens and Neanderthals met.

It is also possible that the women of the competing group were stolen in the process. So it may not have been fiery romances that led to sex between the parties but rather acts of violence. The encounters left demonstrable traces to this day as researchers have known for several years. Around two percent of the DNA in our genome today stems from the Neanderthals—a limited but long-lasting legacy of this long since extinct hominid.

The earth has revealed evidence of the last Neanderthals in layers that are 40,000 or maybe 38,000 years old. At some point during this period, the last of their species disappeared. 'Because of us,' says Jean-Jacques Hublin laconically. From a purely molecular standpoint, the differences between modern humans and Neanderthals are small: a mere 87 proteins separate the two species. Many of them, however, are important for the way the brain works and its development.

Something in modern humans was different. It is possible they took a more aggressive approach than their cousins with whom they were competing; they probably cooperated more effectively in larger teams and in several groups, also showing more empathy and consideration for fellow members.

Experts have found some indications that this was the case. Firstly, modern humans apparently bartered even in the early stages of their time in Europe. For example, mussles from the Mediterranean have been found in Germany. 'That suggests networks operating over larger areas,' Hublin states. 'People knew that fellow humans were living on the other side of the mountains.' And that they wear jewellery and decorate their bodies, as a sign of their allegiance to a larger community consisting of hundreds, perhaps thousands. People who act in solidarity, even if they do not see each other every day. There is nothing like this in the world of the Neanderthals.

Homo sapiens painted pictures from his imagination

Secondly, Homo sapiens painted on cave walls in the early stages of his early European existence, also representing objects that did not exist in reality but only in their imagination. For example, men with lion heads. That means that modern humans recognized stories behind the objects, mythical elements and faith. 'This is a very strong factor which Neanderthals apparently had no feel for', Hublin says.

Things of this nature are 'hard to investigate,' not even with the battery of equipment at the Max Planck Institute in Leipzig. Just how much this frustrates the tech fan is very noticeable. But who knows? Around 40 years ago, when he began his career as a young student, Hublin believed that all the essential elements of human history had already been researched, and that the methodology would not make any more significant progress. 'I could not have been more mistaken.'

Provided by Max Planck Society