March 30, 2017 report

Optically excited structural transition fastest electronic switch ever observed

(Phys.org)—A team of researchers from several institutions in Germany has used laser pulses to change an atomic wire from an insulator to a metal and back again in what the group describes as the fastest electronic switch ever observed. In their paper published in the journal Nature, the team describes their experiments testing the boundaries of phase transition speeds, which have proven that it can occur much faster under certain conditions than was thought possible.

Phase transition speed, as the researchers note, is typically constrained by the speed at which energy can enter a system. Ice turning to water, for example, is constrained by the speed at which heat can enter the ice. The process follows the rules of quantum mechanics, of course, though few theorists have believed it was possible for a transition to occur as fast as the rules allowed. In this new effort, the researchers have shown that such is the case by causing such a transition to occur.

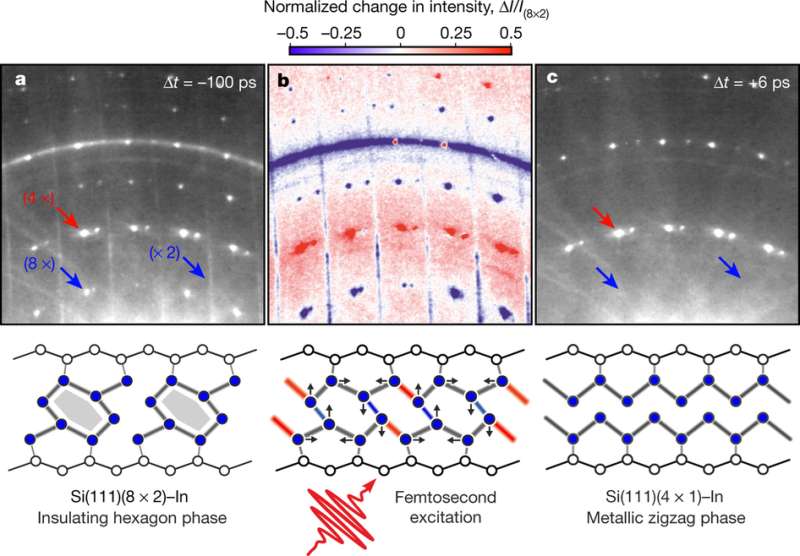

To test the limits of transition speed, the researchers cooled samples of indium on silicon to 30K and then measured the electron diffraction pattern of the surface and found it to be an insulator. They then fired a laser at the sample causing it to heat up very quickly—indium atoms assemble themselves automatically into three atom wide metallic wire when heated. Then they fired another laser pulse to measure how the diffraction pattern had changed. They repeated the process multiple times varying the time between laser firings to see how much time transpired before the insulator became a metal—as it turned out, for times longer than 350 fs. They also tried varying the amount of laser power and found that the more power they applied, the faster the transition—up to a point where it became a constant, which the team noted, was the quantum limit.

Though describing the transition event as the fastest electronic switch ever observed, the team readily acknowledges that they are not suggesting that it could be used to somehow create optical switches for use in practical applications. Rather, they note, it was just some theorists doing some basic research.

More information: T. Frigge et al. Optically excited structural transition in atomic wires on surfaces at the quantum limit, Nature (2017). DOI: 10.1038/nature21432

Abstract

Transient control over the atomic potential-energy landscapes of solids could lead to new states of matter and to quantum control of nuclear motion on the timescale of lattice vibrations. Recently developed ultrafast time-resolved diffraction techniques1 combine ultrafast temporal manipulation with atomic-scale spatial resolution and femtosecond temporal resolution. These advances have enabled investigations of photo-induced structural changes in bulk solids that often occur on timescales as short as a few hundred femtoseconds. In contrast, experiments at surfaces and on single atomic layers such as graphene report timescales of structural changes that are orders of magnitude longer. This raises the question of whether the structural response of low-dimensional materials to femtosecond laser excitation is, in general, limited. Here we show that a photo-induced transition from the low- to high-symmetry state of a charge density wave in atomic indium (In) wires supported by a silicon (Si) surface takes place within 350 femtoseconds. The optical excitation breaks and creates In–In bonds, leading to the non-thermal excitation of soft phonon modes, and drives the structural transition in the limit of critically damped nuclear motion through coupling of these soft phonon modes to a manifold of surface and interface phonons that arise from the symmetry breaking at the silicon surface. This finding demonstrates that carefully tuned electronic excitations can create non-equilibrium potential energy surfaces that drive structural dynamics at interfaces in the quantum limit (that is, in a regime in which the nuclear motion is directed and deterministic)8. This technique could potentially be used to tune the dynamic response of a solid to optical excitation, and has widespread potential application, for example in ultrafast detectors.

Journal information: Nature

© 2017 Phys.org