What happens when soapberry bugs switch to a new host?

Soapberry bugs are a classic evolutionary example of how rapidly insects can switch hosts, adapting from a native to an invasive plant.

Now newly published UC Davis research shows that soapberry bugs have not only lost adaptations to their native host plant but are regionally specializing on an invasive host.

The work, "Adaptation to an Invasive Host Is Driving the Loss of a Native Ecotype," published in the current edition of the journal Evolution, "collapses a classic and well-documented example of local adaptation," said doctoral candidate Meredith Cenzer of the Louie Yang lab, UC Davis Department of Entomology and Nematology. The plant-host switch can lead to disruption of native plant communities and a breakdown of the ecosystem.

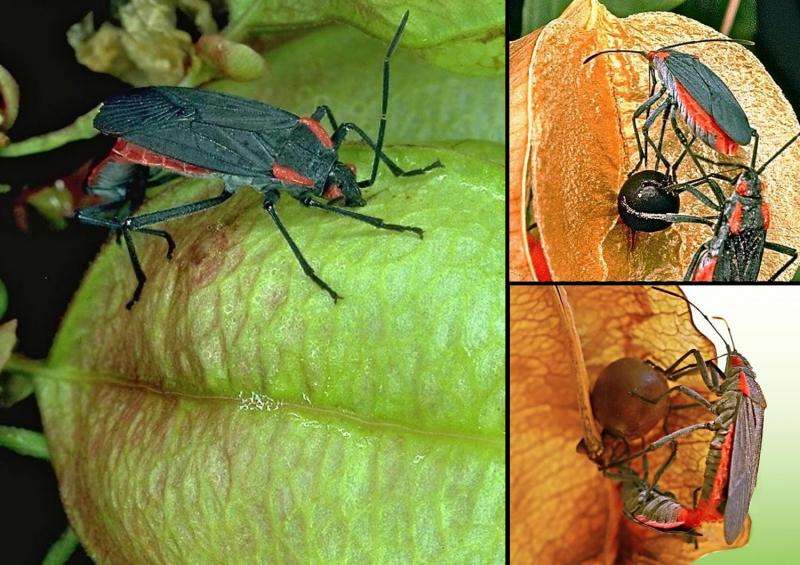

The players involved are the soapberry bug (Jadera haematoloma), also known as "the red-shouldered bug"; its native host plant, the balloon vine (Cardiospermum corindum), and the invasive host, the golden rain tree or Taiwanese rain tree (Koelreuteria elegans).

The study, which took place in Florida, expands on the 1989 groundbreaking research of UC Davis evolutionary ecologist and soapberry expert Scott Carroll, who documented local adaptation in beak length, survival, and development time and other traits between soapberry bugs, balloon vine and the golden rain tree in Florida.

Said Carroll: "Meredith Cenzer's findings carry an important message for those concerned with biodiversity conservation, because she shows that even highly distinct adaptive specializations can disappear rapidly due to human influence on the environment– even in cases where the key native habitat has not been lost."

The soapberry bug, which lives throughout the United States and much of the world, feeds on seeds within the soapberry plant family, Sapindaceae, which includes soapberries, boxelders and maples. Mostly black, it has red eyes, red lateral stripes on the sides of its head and red on its "shoulders" (pronotum). It is often mistaken for the boxelder bug.

"As part of my doctoral dissertation, I documented that this pattern of local adaptation has been lost in the last 27 years," Cenzer said, "and that all populations of soapberry bugs in Florida— even those still found on the native —are now adapted only to the invasive host."

"Locally adapted populations are often used as model systems for the early stages of rccological speciation, but most of these young divergent populations will never become complete species," Cenzer noted in her abstract. "The maintenance of locally adapted populations relies on the strength of natural selection overwhelming the homogenizing effects of gene flow; however, this balance may be readily upset in changing environments."

"All populations that were adapted to the native host—including those still found on that host today—are now better adapted to the invasive host in multiple phenotypes," she wrote in her abstract." Weak differentiation remains in two traits, suggesting that homogenization across the region is incomplete. This study highlights the potential for adaptation to invasive species to disrupt native communities by swamping adaptation to native conditions through maladaptive gene flow."

Cenzer characterized local adaptation as "high performance in one habitat coming at the cost of performance in other habitat types, such that populations specialized on each habitat will have higher fitness in that environment than immigrants from other habitats."

"This results directly in two types of ecological reproductive isolation between locally adapted populations: 1) selection against migrants, who will be outcompeted by residents, and 2) selection against hybridization (if hybrids show intermediate phenotypes), as hybrid offspring will be outcompeted in each habitat by one parental type," she wrote in her research paper. "However, such reproductive isolation relies on ongoing differential selection balanced with low rates of gene flow between habitats. In most well studied systems demonstrating local adaptation, we do not know how perturbation – either to selection pressures or gene flow – will influence the long-term stability of differentiation."

Carroll, who maintains a website, "Soapberries of the World," says the soapberry bugs are "very approachable native guides to how evolution is taking place on earth day." His website shows "how evolution happens every day and why it matters."

A native of Gainesville, Fla., Cenzer received her bachelor of science degree in entomology at the University of Florida in 2009.

"I am broadly interested in evolutionary ecology, particularly in plant-insect interactions, and the balancing roles of selection, gene flow, and plasticity on determining the phenotypes we see in nature," she said. After receiving her doctorate in entomology from UC Davis in the fall, she will start a postdoctoral position at Florida State University with biology professor Leithen M'Gonigle, developing theory on the evolution of dispersal in patchy landscapes.

More information: M L Cenzer. Adaptation to an invasive host is driving the loss of a native ecotype, Evolution (2016). DOI: 10.1111/evo.13023

Journal information: Evolution

Provided by UC Davis